by Joseph Nicolosi, Ph.D.

The easy availability of pornography and consequent addiction to it, has reached epidemic proportions that the media continues to ignore. For the man with SSA, gay porn becomes a particular problem because of the natural but frustrated desires it represents.

As I work with SSA men, it becomes apparent to many of them that its appeal lies in porn’s seeming fulfillment of three emotional drives: (1) Body Envy, (2) Assertive Attitude and (3) Need for Vulnerable Sharing.

If, upon reflection, the client agrees that his attraction to porn is rooted in the above motivations, then we proceed to work on them. If not, then we approach the issue from another direction.

Let us review each of these emotional needs described above, and see how they can be represented in gay porn.

Body Envy

Usually the first identified need is the desire for a body like the personified image. The porn actor possesses qualities of masculinity regarding which the client usually feels inadequate. For each client, those masculine features may differ, but the common elements are muscularity, body hair, large build, and the archetypal image of masculinity, a large penis, which the client often feels are shamefully lacking within himself.

Assertive Attitude

In addition to body image, the client is drawn to a display of directness, non-inhibition and bold aggression. These are exactly what most clients lack in their own life, especially, due to their inhibited and sexualized relationships with other men.

Vulnerable Sharing

With further exploration, the client may identify his attraction to porn, to the idea that it offers open sharing with another man. Sexual activity between two men offers a fantasy image of vulnerable sharing and the illusion of a deep level of mutual acceptance and validation which are painfully absent in his male relationships.

Fantasy for Reality

Diminished interest in gay porn occurs as the client begins to understand that he is pursuing normal, healthy and valid needs through this fantasy and wishful thinking. Yetwhile apparently emotionally “safe,” gay porn offers nothing but temporary relief from loneliness and alienation from other men. The client is encouraged by his therapist to surrender this false intimacy for authentic friendship. While it offers him momentary “safety” from the anticipation of shame-invoking rejection by other men, porn satisfies only in the moment.

The three therapeutic techniques for uncovering the client’s unconscious needs are: (1) Inquiry-Investigation, (2) Body Work, and (3) EMDR. The effectiveness of each technique depends upon the client. The therapist may combine them, but as a general rule, Body Work is more effective than Inquiry-Investigation, and EMDR is more effective than Body Work. (Body Work involves the development of self-attunement and does not involve touching.)

The client’s recognition of porn as merely fantasy projection of unmet needs inevitably leads the motivated client to ask: “Well, then how do I get these needs met?” His question marks the second phase of Reparative Therapy and the process out of gay porn, and more importantly, out of homosexuality itself. Preoccupation with male porn always represents the client’s own sense of masculine inferiority made manifest in these three aspects, and investigation into the life of the SSA client always reveals a lack of authentic male friendships.

Memories of boyhood shaming by dominant males often surface during therapeutic exploration. Porn actors, after all, represent the kind of men who intimidate our client. The client comes to realize that through porn, he can dominate or be dominated by the men who once frightened him. Through porn, he can engage in imaginary play and feel a pseudo-acceptance from the kinds of men who have humiliated and rejected him.

As the client comes to identify how he projects onto the porn image his unmet needs and as he fulfills those needs in real male friendships, the compelling power of the porn image diminishes. Clinical reports tell us that the client may eventually find such images not only uninteresting and non-arousing, but repellant in the same way that such images are experienced by heterosexual men.

by Joseph Nicolosi, Ph.D.

Reparative Therapy® posits two fundamentally distinct self-states: The Assertive Self- State within which the client finds his true self, and the Shame Self-State within which he experiences his false self. In working on overcoming his gay porn addiction, the client comes to realize that in order to become sexually aroused, he must first leave his Assertive True Self and shift into a Shamed False Self. He does this without his awareness, but the eventual realization serves to expose the fantasy nature of the attraction, diminishing the grip of his addiction, as well as his homosexuality.

The Self-State distinction essential to Reparative theory finds theoretical support in the writings of Joyce McDougall. In her clinical studies, she confirms our understanding of homosexual enactment as a gender-based self-reparation.

Among the few contemporary psychoanalysts willing to study what were once called the perversions, Joyce McDougall has investigated the central role of theatre and role-playing in perverse forms of sexual activity, including homosexuality.

McDougall understands “sexual theatre” to be essential to perverse sexual behavior which is rooted in a symbolic attempt to resolve a personal identity conflict. In this regard she confirms the classic psychoanalytic understanding of perverse sexual activity as being rooted in identity confusion. Noting the repetitive-compulsive nature of these role enactments, McDougall found that while her patients complain about the constrained structure of these “erotic theatre pieces,” they could not abstain from their enactments: “…and have to do it again and again and again” (McDougall, 2000, p.182).

The compulsive/repetitive enactment of these rituals represents a symbolic attempt to resolve psychic conflict caused by a problematic parental message regarding the child’s sexuality. In the extreme case of transsexuals, for example, McDougall reports that her patients…“felt that at last they would be recognized by the mother and what she had always unconsciously desired for them” (McDougall, 2000, p.186). These “erotic scenarios” serve to safeguard the feeling of sexual identity but are a technique of psychic survival in that they preserve the feeling of subjective identity. As “compulsive neo-sexual inventions,” they represent the best possible solution that the child of the past was able to find in the face of contradictory parental communications regarding gender identity and sex role. “And they come to the child or the adolescent as revelation of what his or her sexuality is, along with the sometimes painful recognition that it is somehow different from that of others: there is no awareness of choice” (McDougall, 1986, p.21). Further, she saw these dramatic and compulsive enactments as ways of preserving the narcissistic self-image from disintegration: “Thus the act becomes a drug intended to disperse feelings of violence, as well as a threatened loss of ego boundaries, and a feeling of inner death. Meanwhile the partner and the sexual scenario become containers for dangerous parts of the individual. These will subsequently be mastered, in illusory fashion, by gaining erotic control over the other or through a game of mastery within the sexual scenario” (McDougall, 1986, p. 21).

Bibliography

McDougall, Joyce, Arnold Modell, and Phyllis Meadow (2000) “Sexuality Reconsidered: A Panel Discussion.” Modern Psychoanalysis, 25:181-189.

McDougall, Joyce, (1986) “Identifications, Neo-needs and Neo-sexualities,” International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 67:19-30.

Nicolosi, Joseph (2009), Shame and Attachment Loss: The Practical Work of Reparative Therapy. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press.

by Joseph Nicolosi, Ph.D. and Linda A. Nicolosi

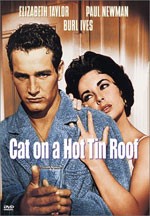

“Cat on a Hot Tin Roof” was a Broadway play, later made into a compelling movie starring Elizabeth Taylor and Paul Newman.

The play is heavily biographical for its author, Tennessee Williams. Shy, sensitive and frail as a child due to a debilitating bout with diptheria, Williams believed that he was a disappointment to his father, a man known for alcoholism and a violent temper. Williams’ mother was a Southern Belle who was known as a strong-willed social climber; she focused her high expectations on her son when her marriage went sour. Thus the playwright’s parents seem to have created the environment of what we know as the Classic Triadic Family System, a common background in the life of homosexual men.

Tennessee WilliamsWhen in college, Williams briefly flirted with heterosexuality, as he had a crush on a female classmate. Eventually, though, he was drawn into homosexual relationships. Williams never could seem to be acceptable to his fraternity brothers, who considered him shy and awkward. He became an alcoholic and drug addict, and eventually he died of an overdose, but not before a remarkable artistic career during which he produced some of the greatest plays of the twentieth century, many of which were known to be autobiographical.

——————

The plot of “Cat” centers on “Big Daddy”’s birthday party. An aging, wealthy Southern Estate owner, “Big Daddy” is a gruff, commanding patriarch who uses material rewards as substitute for love. “What makes Big Daddy so big? …His big heart, his big belly …” his family chants, “…his big money!”

This is a play about how Big Daddy and his two sons are each deficient in the three life-forces that create masculinity: the Reality Principle, procreation, and the ability to love another person. In fact, the challenge to confront reality–resisting the temptation to substitute a narcissistic universe of make-believe– is a repeated theme in the plays of Tennessee Williams. In “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof” (said to be his favorite creative work), he seems to have been trying to work out his own struggle with reality, and with his sexuality as well.

When the story begins, Brick, the youngest son (played in the film by Paul Newman) lacks all the necessary elements of masculinity. He is neither realistic, procreative, nor loving. He is the boy stuck in a youthful narcissistic world, a rebel against the universal law, substituting fantasy and thus preserving his narcissistic illusions. His wife Maggie (Elizabeth Taylor) calls him “Boy” or “boy of mine.” He is not yet a man. He dreams of his lost past as a youthful athlete, and of a man (“Skipper”) he had a romantic fascination with. Now, he can no longer be intimate with his wife. He is constantly drunk.

Yet his name is suggestive of a solid building material for the family empire, should he ever break free of his anger and illusions.

Trying to re-live his glorious football past, Brick injures his ankle the night before Big Daddy’s birthday party while at the high-school track field (drunk) trying to jump the hurdles. Throughout the play, he is on crutches. Asked “What were you jumping high hurdles for? Brick answers, “Because I used to, and people like to do what they used to do after they’ve stopped being able to do it.”

Brick’s father, Big Daddy, represents two of the three masculine principles: the reality principle and procreation. He lives out a harsh reality (ruthless money-making) and is committed to family and to promoting his lineage. When he was young and single, he found out that Big Mama was carrying his child. He said to her, without love or tenderness: “That’s my kid, ain’t it? I want that kid. I need him. He ain’t going to have nobody else’s name but mine. Let’s get the preacher. That’s what marriage is for. Family.”

Burl Ives as Big Daddy (left) and Paul Newman as BrickBut Big Daddy’s flaw is that he does not like people. In his ruthless money-making, he has forgotten how to love. Because he is disconnected from this primary masculine principle, his wife, Big Mama, is also love-deprived and ungrounded in reality. “Truth!” Big Mama says. “Everybody keeps hollering about the truth. The truth is as dirty as lies!”

Big Mama’s relationship to Brick is possessive and intrusive, excluding her other son, Gooper. Soon after the story begins, she hears the bad news that Big Daddy has terminal cancer, and she cries out: “I want Brick. Where’s my Brick? Where’s my only son?”

Gooper represents the opposite of rebellious Brick. Gooper is the “good” sort of son who follows orders and does all the right things expected of him, keeping his wife continually pregnant with a brood of smiley-faced but malevolent children, even while Gooper and his wife secretly plot to take over the family inheritance. But he is a hollow male; materialistic and legalistic. Like Big Daddy, Gooper lives a sham reality, and like Big Daddy, he cannot love. He can procreate, but he cannot give life. His procreative power is soulless, creating not children, but unloved wild sub-creatures who have been given dogs’ names. Like animals, his children represent “a flesh-and-blood dynasty…waiting to take over”; Brick’s wife Maggie calls them “no-neck monsters” because “their fat little heads sit on their fat bodies without a bit of connection.”

Gooper’s wife, like her husband, is also soulless and money-focused. Along with Gooper, she portrays a picture-perfect family image. She uses her children to help her win the inheritance with an annoying parade of theatricalities designed to “entertain” Big Daddy and make him feel good about himself.

Married to a man who is incomplete, Gooper’s wife is unable to fulfill her feminine nature. She can procreate but cannot give birth to genuine human life. She is the Negative Feminine. Maggie, Brick’s wife, calls her “that fertility monster.”

Maggie is the only sympathetic and noble person in this dysfunctional family. Brick’s withholding of love and unrelenting cruelty toward her –while he remains obsessed with a man from the past, Skipper– has forced her to undergo, in her own words, “this horrible transformation” into becoming “hard and frantic and cruel.”

The plot repeatedly returns to the Brick’s relationship with the mysterious and unseen Skipper. This is the man who is the unspoken source of his and Maggie’s marital conflict. The relationship with Skipper was intense and mutually dependent with the suggestion of being homoerotic. Despite the devastating effect of this situation on Maggie, Brick refuses to talk about it.

Seeking the male connection he did not get from his father, Brick made Skipper the special person in his life, overshadowing and competing withhis wife. Without a man’s masculine blessing he cannot become a procreative man, cannot live in truth, and cannot love a woman. Brick wants to take masculine love from Skipper, but Skipper needs it as well, and Skipper’s suicidal end is the final result. And so Brick broods, and numbs his misery in alcohol.

A turning point in the play occurs whenBig Daddy wants to have a “private conversation” with Brick.

In his crude style he asks what is troubling his son. Revealing some glimmers of true love, Big Daddy says, “Boy, sometimes you worry me. Why do you drink?” Brick refuses to answer. All he can say is, “It’s too painful and it’s no use. We talk in circles. We have nothing to say to each other!”

Big Daddywants to know the truth about his son’s special relationship with Skipper, which he sarcastically refers to as “this great and true friendship.” Whatever happened that night when Skipper killed himself, Skipper had been devastated and screamed for help, but Brick could not save him. Brick explains this with a rhetorical question: “How does one drowning man help another drowning man?”

Big Daddy persists; asking again, “Why do you drink?”

In reply, Brick cries out; “Mendacity! It’s lies and liars! Not one lie or one person. The whole thing.” In deeper honesty, Brick adds, “That disgust with mendacity is really disgust with myself. That’s why I’m a drunk. When I’m drunk I can stand myself.”

Big Daddy agrees about the pretense that characterizes the family; but here, he reveals his fundamental difference on the principle of reality. Unlike Brick who lived with the family’s mendacity and turned it into self-hate, Big Daddy takes on gritty reality and just sees lies and falsity as an unchangeable fact of life. He answers Brick: “Look at the lies I’ve got to put up with. Pretenses, hypocrisy! Pretending like I care for Big Mama. I haven’t tolerated her in years. Church! It bores me, but I go. All those swindling lodges, social clubs, and money-grabbing auxiliaries that’s got me on their number-one sucker list. Boy, I’ve lived with mendacity. Why can’t you live with it?”

Illustrating their differing attitude on life, Brick (who dulls his own pain with alcohol) offers Big Daddy some morphine to kill the pain of his own cancer, but Big Daddy refuses: “It will kill the pain, but kill the senses, too. When you’ve got pain, at least you know you’re alive. I’m not going to stupefy myself with that stuff. I want to think clear. I want to see everything and feel everything.”

The breakthrough occurs when father and son are standing in the basement of the house (revisiting the “unconscious,” or place of buried memories) and surrounded by his mother’s outrageous collection of “stuff” — statues, pieces of grotesque faux art, and garish furniture covered in cobwebs, which have been put into storage after her previous wild decorating sprees. Big Daddy, softened by the knowledge of the approach of his death, and ready to face some of the truths of life, sits amidst that piled-up junk in a moment of uncharacteristic vulnerability and tenderness.

Brick is still looking for love, with either man or woman. But Big Daddy had given up the search: “The truth is pain and sweat, paying bills and making love to a woman that you don’t love anymore.”

They begin an honest talk about Big Daddy’s cancer. Now, the inevitability of his demise shatters the family’s false-happy illusions and establishes the basis for an uncharacteristic tenderness between father and son. Their lifelong arguments at first resume, until Brick cries: “All I wanted was a father, not a boss! I wanted you to love me. We’ve known each other all my life and we’re strangers!”

Then Big Daddy recalls his own father: “I was ashamed of that miserable, old tramp….” Then he adds, unexpectedly, “I reckon I never loved anything as much as that lousy old tramp.”

Suddenly, tenderly recalling his father’s love, Big Daddy is open to loving his own son, which immediately links the three generations of men and breaks through the deadening barrier of pretense. Big Daddy’s love, expressed for the first time, frees Brick to transform himself from a self-preoccupied alcoholic to a man alive to himself and able to love; and through this transformation, he can now respond to Maggie’s womanhood.

Big Daddy and Brick, perhaps for the first time in a lifetime,cry together.

Then in a moment of wild and joyful emotional release, Brick smashes his mother’s ridiculous collection of discarded “stuff.” Throwing aside his crutches, he hobbles up the stairs, exultant with joy. Maggie sees his joy, and she tells the family that she has new life in her body, and that the family will now continue through a child that is Brick’s.

Gooper and wife laugh sarcastically; they say they have heard the begging and pleading through the bedroom walls at night, when Brick refuses to be intimate with Maggie, so they know this story of her pregnancy cannot be true. Big Daddy’s family and his inheritance, they insist, will continue only through them and their side of the family.

But Brick grabs his wife, full of joy, takes her to the bedroom, kicks the door shut, embraces her with spontaneity and love for the first time since the play began. He exults that it is true– that there will soon be new life in Maggie’s body as well.

And so the play ends.

by Joseph Nicolosi, Ph.D.

I am often asked, “If homosexuality is usually caused by an internalized sense of masculine inferiority, how do you explain the masculine type of homosexual?”

I explain it as follows. The reparative principle is the same: there is an eroticized attempt to capture the lost masculine self. The masculine type of homosexual man suffers the same internal sense of masculine deficit as the more androgynous or feminine type, but in boyhood, this man typically needed to develop an external “macho” persona to fend off emotional abuse. The very masculine actor, Rock Hudson, the quintessential “heart throb” of the 1960’s, confessed: “There is a little girl inside of me” (Davidson, 1986).

An early environment of severe humiliation has taught some masculine types of homosexual men not to show weakness and to have contempt for their own vulnerability. Bullying typically came from the father, an older brother or male peers at school. In these situations, to show weakness often provoked greater assault and so denial of their vulnerability was necessary for survival.

This maneuver into a hyper-masculine façade is a “reaction formation,” which entails, as Freud said, an “identification with the aggressor.” It is a primitive form of self-protection in which the victim gains a fantasy security by imitating the feared person (*).

This same shift in identity is also seen in the masculine lesbian who may have perceived her mother – and therefore femininity – as weak; such a person therefore joins, through identification, with her mother’s spouse (the father) and she becomes Daddy’s little boy.

The masculine-type homosexual man often displaces his own need for love, comfort and protection onto a younger, weaker male. This is similar to the situation we see in another sexual deviation, pedophilia, where the man may wish to “give love” to a boy as he wished he himself had been loved (although in a different, non-sexualized way) when he himself was a child. This “innocent young boy” image he is so drawn to, is a projection of the abandoned boy that still exists within himself. Self-psychology explains this displacement of his unmet needs onto the disavowed self as a form of narcissistic identification.

When this masculine type of homosexual man feels insecure, he resorts to the reparative sexual enactment of giving comfort to the frightened boy within, by seeking closeness with a vulnerable younger man. Therefore he is often attracted to the younger, less masculine type of male – the innocent, adolescent type of partner who represents the suppressed part of himself that had to be denied in order for him to survive his boyhood. So this masculine type of homosexual now gives protection and “love” (albeit sexualized) to the youth, something which he himself once longed for.

Therapy necessitates guiding the masculine homosexual client with such a background toward abandoning the false macho, hyper-masculine facade and discovering his genuine masculine self. A genuine masculine self is characterized by, among other things, a natural vulnerability. This process also necessitates resolving his childhood trauma of abuse and intimidation. Through this resolution, he no longer has the compelling need to reenact his reparative sexual fantasy.

————————

(*) This phenomenon is similar to the Stockholm Syndrome in which captives identify with their abductors. The case of Patty Hearst, heiress to the Hurst media empire, is another example. For two months, Patty was kept in a closet and “brainwashed” by her captors, culminating in her assuming their identity. A willing convert to their revolution, she took the name “Tanya” (a tribute to the wife of Che Guevara) and participated in the robbery of a San Francisco bank.

Reference:

Davidson, Sara (1986). Rock Hudson: His Story. New York: Morrow.

Following is a letter written by a graduate psychology student to his college professor.

The student has struggled personally with same-sex attractions. In this letter, he seeks to educate his professor about the unmet developmental needs that lay the foundation for homosexual attraction.

He describes the unmet needs he recognizes in his own background, and at the same time, explains why the “born that way” theory simply doesn’t account for the development of his homosexuality.

Dear Professor,

I am enjoying the multicultural counseling class immensely. But there is a subject, which, when it comes up, I feel like a distinct minority, and it is causing me pain. You appear to hold a strong point of view on this subject, which I know springs out of good intentions, but for which I feel invalidated.

I would like to begin by referencing a quote from page 205 of the textbook we are reading. In referring to African-Americans, it quotes:

“Environmental factors have a great influence on how people develop. This orientation is consistent with African American beliefs that racism, discrimination, oppression, and other external factors create problems for the individual. Emotional disorders and antisocial acts are caused by external forces (system variables) rather than internal, intrapsychic, psychological forces.” (Sue & Sue, 2008)

The quote seems to imply that the black experience of oppression is due to what they grow up with and face environmentally, rather than any intrinsic difference. And that it is these environmental factors which are the problem. I agree with this.

In my own life, the “environmental factors” that influenced my growing up caused many maladjustments. You know, for example, that my dad sexually abused me. In addition, core needs of mine were unmet. It’s a theme you read about in my personal life story paper in the Human Development Theories class you taught. I believe a principal need of mine that went unmet was attuned nurturance from my dad. To me he was such an unattractive and abusive individual that I can remember as early as age 4, detaching from him as a kind of defense response. This has been termed “defensive detachment.”

I turned instead to my mother, who was only too eager to have “a special little boy” to look up to her. I believe, in fact, that I was meeting her emotional needs as much as, if not more than, she was meeting mine. This set up a very unhealthy triangulation dynamic in my upbringing.

My dad was scary to me, and I felt I needed to suppress my natural masculine instincts in order to survive. Take for example, the day when I was six years old, and stood at the front of the line with my family, and decided to express masculine initiative and care for my siblings. We were standing in line to order donuts at one of these places with 50 different donut varieties. I remember how overwhelming it felt to choose which donut to order. I imagined that the rest of my family felt this way too. So when I saw a piece of brown donut on the counter top within my reach, I thought I could narrow the field on behalf of my family. I proudly announced “I’ll taste the chocolate donut!” I then picked up the donut piece and popped it into my mouth.

I felt like I was expressing qualities of both problem-solving and love for my family. This was true masculine initiative, coming from a six-year-old boy. What happened? My dad started slapping me in the face, with a mean, ominous look. No words were spoken. I ran to my mom and buried my head in her skirt. She said nothing on my behalf to my dad.

I share this with you because this, and countless other little incidents like it, had a dire effect on my self-concept as a male, and my sense of personal power. My self-esteem kept sinking and I began to portray myself as a victim, seeing most males as mean and scary, like my dad. I had a real problem. I had defensively detached from my dad, and was also defensively detaching from the boys at school as well. BY DEFAULT, NOT BY CHOICE I identified with girls, because it was safer to be around them, and my subjective experience from males had been so negative.

So what do you think happened to me in adolescence? I WAS SEXUALLY ATTRACTED TO OTHER BOYS, NOT TO GIRLS!

Does this mean I was “born” gay? A counselor I once had seemed to imply that an abusive father “knows” when his little toddler son is gay, and unconsciously abuses him for it. It’s such an outrageous implication, it makes me vomit.

Did I want homosexual arousal? No. Did I choose it? Again, no. Was my upbringing a major factor in this? Sadly, I find that the psychological community in general would admit that it was a small factor that was meaningless, because I was probably born gay. The Sue & Sue textbook states on page 445:

“As one researcher concluded, “Homosexuality in and of itself is unrelated to psychological disturbance or maladjustment.”

For many gay men I have known or met, I COULDN’T DISAGREE MORE. And it is sad that an enlightened textbook as this has given us a chapter on sexual minorities that is so single-track.

Also on page 445, is a discussion of the APA removing homosexuality from the DSM in 1973. It goes on to state:

“However, it did create a new category, ego-dystonic homosexuality, in the third edition of the DSM…for individuals with (1) ‘a lack of heterosexual arousal that interferes with heterosexual relationships’ and (2) ‘persistent distress from unwanted homosexual arousal.’ This category was eliminated in the face of argument that it is societal pressure and prejudice that create the distress.”

Wow, I would definitely have fit that DSM description, and perhaps a therapist could have addressed it with me. Too bad they removed it.

Why was it that I could not embrace a gay identity and gay sexuality? I can’t speak for other men, but I reject the notion that it is strictly because of societal disapproval. In my own case:

My sense of masculinity had been extremely compromised as a boy, and this was related to abuse and rejection from males. I felt so lacking in masculine affirmation, which to me is such a natural and normal need for boys (as is feminine affirmation for girls). Yes, I desperately needed connection with the masculine, and in part because I was afraid of other boys, I didn’t like sports, which is a major avenue whereby boys in our culture get that masculine connection. I couldn’t seem to get what I so desperately needed. It’s as if my psyche screamed “Get connection with masculine, and get it now!” So no wonder my bodily response in adolescence was one of sexual arousal toward other boys!

So why didn’t I “go for it”? It is true that my religious/ spiritual convictions played a part as a huge protective factor. But beyond that, I knew something profound at an intuitive level. That capitulating to my sexual desire for other boys would be to capitulate to the abuse, and to the family and social factors that had caused me great emotional pain in the first place. Instead of feeling better about myself as a male, this would likely cause me to feel worse about myself. I do not attribute this feeling to societal pressure, although I admit that such pressure is strong. For me it had to do with wanting to access my own masculinity, rather than cannibalizing it from another male. And also, despite being “exciting,” the idea of sex with a male felt “dark.”

In my journey, I certainly understand that piece about “darkness.” I believe that being sexually and emotionally abused at a very young age was a large part of that darkness. The reparative drive of the human psyche looks to the familiar, in order to try to promote reparation, or “healing” (witness the women who were battered by their fathers, who go on to marry a batterer). On some level, I believe I intuitively understood that sex with another male would have been like a re-creation of the sexual abuse I had experienced.

Through lots of personal growth and prayer, I felt my self-esteem improve as I moved into young adulthood. Beginning a professional career in my 20’s was difficult, but I stuck it out. When I began to hit my stride in my department, my manager, who was a man I looked up to, as well as other men in the office, praised me, and affirmed me. I felt AFFILIATED with men in a positive way, for perhaps the first time in my entire life.

How interesting that this was the period when I met the woman who was to become my wife, AND HAD GENUINE AND COMPELLING SEXUAL AROUSAL TOWARD HER. Having sexual arousal TOWARD A WOMAN had never happened prior to this in my entire life! However, after a time, the same-sex attraction returned, when healthy masculine affiliation waned again. And in my private thoughts and moments, my sexual fantasies would be about men, not women.

After my divorce quite a number of years later, I attended an intense, week-long residential therapy program, geared for people who grew up in dysfunctional families–often with a substance-abuse component, and the problems which derive from that. The program was excellent, and tears it evoked in me were intense. It was like lancing a wound. We were, of course, encouraged to find a therapist when we returned home, if we did not already have one. Before leaving the retreat, I spoke a few minutes to the clinical director of the program, to tell her how much it had meant to me. I then brought up the (to me) troubling subject of my unwanted same-sex attractions. Her response? She shrugged her shoulders, as if the feelings that had damaged my marriage, and were destroying my life, were irrelevant! That’s SHOCKING to me.

So here are the stated choices, from the standpoint of the psychology profession: That you are either heterosexual, or, if you feel attracted to the same sex, you are either gay or bisexual, and you should embrace your gay/bisexual identity. But Professor, neither of those “shoes” fit me! And I believe it is destructive to imply that the battle is between liberals and conservatives, or those who believe in gay rights, and those who don’t. I vehemently disagree with the tone of the rhetoric of some right-wing churches, and with ANYONE who would bring harm to a gay person, be it physical or psychological harm. And yet, the implication from our profession is that a gay lifestyle is totally healthy, and should be embraced by any and by all. I disagree with that profoundly.

So I find myself in a distinct, and yes, oppressed minority position on all of this, which rejects both the right and left. The issues are so deep, and the arguments, in my view, by both the right and the left, so shallow, and take into account surface manifestations only, rather than looking deeply into causes.

I also believe that there are profoundly unhealthy behavior cultures rampant in the gay male community, which are harming men. (This has nothing to do with religious moralism). But the psychology profession seems hostage to political correctness.

Consider a book that came out a few years ago called “Destructive Trends in Mental Health: The Well-Intentioned Path to Harm,” by Rogers Wright and Nicholas Cummings. Cummings is past president of the APA, and Wright is the founding president of the Council for the Advancement of Psychological Professions and Sciences. From a book review in the January/ February 2006 “Psychotherapy Networker,” I quote the following:

“Their charges of runaway political correctness add up to an exhausting critique…Many lesbian and gay activists want to forbid the right to treatment for troubled clients who come into therapy wishing to change their sexual orientation.” (How outrageous—so much for client self-determination!)

“What seems to bother Wright, Cummings, and the other contributors to this book more than the content of political correctness is its baleful effect on the scientific foundations of psychology. They believe that political correctness is behind the shortsighted view that science is somehow irrelevant to what psychologists do. For instance, Cummings says that he supported the 1974 American Psychological Association resolution stating that homosexuality isn’t a psychiatric condition. What’s often forgotten, however, is that further resolutions were passed, prescribing the need for more scientific research into the issue. But none has ever been done. In short, writes Cummings, “the two APA’s had established forever that medical and psychological diagnoses are subject to political fiat.”

Some organizations with religious affiliations claim to help men and women with unwanted same-sex attractions (SSA) to change. But I am wary, because of what I view as a potential religious agenda. There are, however, some organizations which are secular, and which are pioneering a relatively new model for healing from unwanted SSA. Several years ago, I attended an experiential weekend put on by an organization called “People Can Change” (www.peoplecanchange.com) That weekend was among the most powerful experiences of my entire life. In preparation for the weekend, they sent an article about the principles behind change. This (roughly 10 page) article is a very cogent and logical explanation of the causes of SSA, (for males) and the implications of the work needed to heal. Professor, I have attached it to this e-mail, and encourage you to read it thoughtfully, if you are willing to learn about environmental dynamics which can cause SSA in men. My own life story makes so much sense in light of what is written in this document. In fact, it virtually is my life story.

Another secular organization is the National Association for Research and Therapy of Homosexuality (www.narth.com). This is a network of therapists and psychologists who believe in a patient’s right to choose “reparative” therapy for overcoming unwanted SSA.

So how has “change” worked in my own life? Whereas I used to isolate, I now have healthy friendships with men, which is meeting those needs for affiliation and affirmation from my own gender. Same-sex attractions have gone from what I would describe as “troublesome” to now only very occasional, and when it does happen, they are far less intense than they once were, and fade quickly. I now can spot the old emotional issues that I formerly was unaware of, and which used to translate into sexual arousal. I have a much improved body self-image now, and have had two relationships with women in the last four years. But more importantly, I believe that I have been shedding an imposed identity and embracing my true authentic identity.

Is this kind of reparative therapy for everyone? No. Is it hard work? Yes. As you know, the neural networks of the brain don’t change overnight.

Professor, there are many more details about my journey, but I believe I have written enough. The work I have done toward sexual reorientation has been so profound, so life-enhancing, that it feels a bit like the lifting of a curse. I see this as a potential practice for me in the future: to help other men heal from unwanted SSA.

Please know that I admire you greatly as both a teacher and as a caring person (why else would I spend literally the better part of entire day thinking about and writing this?). Thank you for being open to viewing such a “charged” subject in a new and thoughtful way, and to challenge your own conceptions. Thank you for honoring my experience and my walk, and the experience and walk of those who will come after me.

Sincerely, and with care,

A Graduate Student in a master’s program in counseling

Excerpts from the professor’s response:

Hi Student,

Thank you…for trusting me with so many personal details of your story,

for telling me when I do something that hurts you, for taking the time to share your thoughts with me…

I have read your letter four times now, and will undoubtedly need to read it a few more times. Each time I am humbled and honored that you’ve talked to me, and that I get to know you… as well as so sad that I have invalidated your experience. I haven’t read the article yet, but have printed it out to read later tonight. But I didn’t want to make you wait that long for my reply, as I imagine you are wondering at my reaction…

I think your story is so important to tell, as (like you say) some of the views around sexuality are deeply imbedded in our professions… Your story has definitely got me thinking, and I really thank you for taking off more of my blinders. You are so committed and passionate about self discovery, and so am I! So I thank you for making me more aware of what I say and how that impacts others.

Please can we talk more? Or do you feel like you’ve said enough?!?

Professor

by Joseph Nicolosi, Ph.D.

The scientific prestige of the American Psychological Association (APA) was evidenced recently during the legal debate over treatment for unwanted homosexuality.

Over and over in the courtroom, one piece of evidence trumped all other information — the APA’s’ Task Force Report, “Appropriate Therapeutic Responses to Sexual Orientation” (2009).

With unbroken success, that gay-activist trump card was used as the decisive factor in all recent court decisions. For this reason, it is necessary to reexamine the Report’s origins.

While numerous methodological critiques have been made against the Report (1), this paper will focus exclusively on the inherent bias of the seven members who made up this panel of experts.

When “The Foxes Are Guarding The Henhouse”

If the APA wanted to do an objective investigation of the therapeutic effectiveness of sexual-orientation change therapy using a representational demographic, and if 1-2%, of the U.S. population is gay, then we would expect that of the seven Task Force members, perhaps one would be gay. But of the seven members of the Task Force Committee, six have publicly documented themselves as gay-or bisexual-identified.

Not only were these members gay, but all – including the one non-gay-identified member, and the one bisexual member- engaged in gay activism before their selection for the Task Force.

In my previous paper, “Why Gay Cannot Speak for Ex-Gays,” I offered a psychological explanation as to why the identity process of “coming out” which results in a gay identity will bias the individual from accepting the possibility of change for others. Abandoning the hope of ever overcoming their unwanted homosexuality (which is a necessary prerequisite for accepting a gay identity) creates a resistance in the mind of the gay-identified person that change could be possible for someone else: “If it was impossible for me, then no one else can do it.”

Has Homosexuality Been Scientifically Proven To Be “Positive”?

Beside this bias, another overlooked fact is that, prior to the start of their investigation, the Task Force members admitted to being opposed to the very existence of reorientation therapy, based on their view that homosexuality must be viewed by others as “positive.” In the introduction of their report, they state:

“The task force…[accepts]… the following scientific facts:

Same-sex sexual attractions, behavior, and orientations per se are normal and positive variants of human sexuality—in other words, they do not indicate either mental or developmental disorders.” (2).

Here the Task Force members are “a priori” acknowledging that they would not consider any non-normative causes of homosexuality, nor any reasonable motivation for a person to change. But this view is not a “scientific fact” — it has not been scientifically demonstrated; and, furthermore, it is as much a question of philosophy as of science.

The Task Force’s assumption that a homosexual orientation is a good and desirable orientation (and by logical extension, that any attempt at change is bad for the individual), was not unique to the Task Force members, but reflects the official policy of the APA. The Report was from the start, not intended to open an investigation into the matter, but to reaffirm APA policy.

In addition, before approval, every applicant for admission to the Task Force had to be first “recommended” by the APA Committee on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgendered Concerns (3).

Who, then, were the seven APA Task Force members?

Chair: Judith M. Glassgold, Psy. D. is a lesbian psychologist. She sits on the board of the Journal of Gay and Lesbian Psychotherapy and is past president of APA’s Gay and Lesbian Division 44.

Jack Drescher, M.D. is a well-known gay-activist psychiatrist, and serves on the Journal of Gay and Lesbian Psychotherapy and is one of the most vocal opponents of Reparative Therapy®.

A. Lee Beckstead, Ph. D. is a gay counseling psychologist who counsels LBGT-oriented clients from traditional religious backgrounds. He is a staff associate at the University of Utah’s Counseling Center. Before joining the Task Force he expressed strong skepticism that reorientation therapy could be helpful. As a Mormon he urged the Mormon Church to revise its non-gay-affirming policy on homosexuality and instead, to affirm church members in a gay identity.

Beverly Greene, Ph.D., ABPP, is a lesbian psychologist and was the founding co-editor of the APA Division 44 (Gay and Lesbian division) and serves on the Psychological Perspectives on Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Issues.

Robin Lin Miller, Ph.D. is a bisexual community psychologist and associate professor at Michigan State University. From 1990-1995, she worked for the Gay Men’s Health Crisis in New York City and has written for gay publications.

Roger L. Worthington, Ph.D. is not homosexual, but in 2001 was awarded the “2001 Catalyst Award,” from the LGBT Resource Center, University of Missouri, Columbia, for “speaking up and out and often regarding LGBT issues.” He co-authored “Becoming an LGBT-Affirmative Career Advisor: Guidelines for Faculty, Staff, and Administrators” for the National Consortium of Directors of Lesbian Gay Bisexual and Transgender Resources in Higher Education.

Clinton Anderson, Ph.D. is a gay psychologist, officer of the APA’s Office for Gay, Lesbian and Bisexual Concerns and served as Task Force Committee Liaison.

Remarkably, the APA rejected, for membership on this committee, every practitioner of sexual-reorientation therapy who applied for inclusion.

The rejected applicants included–

-

NARTH Past-President A. Dean Byrd, Ph.D., M.P.H., M.B.A., (now deceased), a distinguished professor at the University of Utah School of Medicine, longtime practitioner of reorientation therapy, and co-author of several peer-reviewed journals and articles studying change of sexual orientation. Dr. Byrd is considered one of the foremost experts on same-sex attraction and reorientation therapy. He has published numerous articles on sexual reorientation, as well as gender and parenting issues.

-

George Rekers, Ph.D., Professor of Neuropsychiatry and Behavioral Science at the University of South Carolina, editor of the Handbook of Child and Adolescent Sexual Problems, a National Institute of Mental Health grant recipient, author of the book Growing Up Straight, as well as numerous peer-reviewed articles on gender-identity issues;

-

Stanton Jones, Ph.D., Provost and Dean of the Graduate School and Professor of Psychology at Wheaton College, Illinois, the co-author of Homosexuality: The Use Of Scientific Research In The Church’s Moral Debate, and a second book, titled, Ex-Gays? A Longitudinal Study of Religiously Mediated Change in Sexual Orientation.

-

Joseph Nicolosi, Ph.D. (author of this article), a founding officer of NARTH, practitioner of Reparative Therapy® for over 30 years, and author of Reparative Therapy of Male Homosexuality and the 2009 book, Shame and Attachment Loss.

-

Mark A. Yarhouse, Ph.D., is Professor of Psychology, Doctoral Program in Clinical Psychology at Regent University in Virginia Beach, Virginia. Dr. Yarhouse is co-author of Homosexuality: The Use Of Scientific Research In The Church’s Moral Debate and Ex-Gays? and A Longitudinal Study of Religiously Mediated Change in Sexual Orientation and has published many peer-reviewed articles on homosexuality.

When Clinton Anderson, Chairperson of the Task Force, was confronted at an APA Town Hall Meeting as to why the above names were rejected, Dr. Anderson evaded the question with a bit of sleight of hand: “They were not rejected, they just were not accepted.”

If the APA truly wished to study sexual orientation–a values-laden issue with a strong (but unacknowledged) worldview component, they would have followed established scientific practice by choosing a balanced committee that included individuals with differing worldviews. They would have included clinicians who respect their traditionalist clients’ views on sexual expression. Instead, they chose only psychologists who are these clients’ philosophical opponents.

The scientific bias of the Task Force is further evidenced by four facts:

-

The Task Force failed to reveal the well-documented, far-higher level of pathology associated with a homosexual lifestyle. If they had truly been interested in science, they would have believed it their duty to warn the public about the psychological and medical health risks associated with homosexual and bisexual behavior. Their failure to advise the public about the risks not only betrays their lack of commitment to science, but prevents sexually confused young people from accurately assessing the choices available to them.

-

Why do some people become homosexual? The reader of the Report might justifiably expect some discussion of the varying factors associated with the development of same-sex attractions. This whole field of study was ignored.

-

The Task Force did not study individuals who reported treatment success. Even if (for the sake of argument) therapeutic change had been reported to be successful in only ONE case, then the committee should have asked, “What therapeutic methods brought about this change?” But since the Task Force considered change undesirable, they showed no interest in pursuing this avenue of investigation.

-

The Task Force’s standard for successful treatment for unwanted homosexuality was far higher than that for any other psychological condition. What if they had studied treatment success for narcissism, borderline personality disorder, or alcohol/food/drug abuse? All of these conditions, like unwanted homosexuality, cannot be expected to resolve totally, and usually necessitate some degree of lifelong struggle. Many of these conditions are, in fact, quite notoriously resistant to treatment. Yet there is no debate about the usefulness of treatment for these conditions: and psychologists continue to treat them, despite their uncertain outcomes.

A Gay Critique of Traditional Religion

The Task Force Report speculated about two types of response to homosexuality– first, as seen in the person who claims his homosexuality as a source of his deepest self-identity: and second, in the person who believes he was not designed for homosexuality and chooses to reject it as a source of identity. They are defined by:

Organismic Congruence (claiming a gay identity), defined as “affirmative … models of LGB psychology” and “living with a sense of wholeness in one’s experiential self” (p. 18).

Telic Congruence. This applies to people of faith who do not wish to identify with their homosexuality; they instead choose to live consistently within their values. Therefore, to live out one’s traditionalist religious values, according to the Task Force, is to make oneself incomplete and inconsistent within one’s experiential self.

In creating this distinction between organismic congruence and telic congruence, the members of the Task Force offer us a misleading dichotomy. Seen through the perspective of their own gay identities, the Task Force therefore claims that persons striving to live a life consistent with their religious values are denying their true, embodied selves. Religious believers who choose not to gay-identify therefore must constrict their true selves through unnatural behavioral control and cannot experience organismic wholeness, self-awareness and a mature development of their identity. These attributes are only possible for individuals who, like the Task Force members, identify with their same-sex attractions.

The Task Force members evidently cannot understand that the person of traditional faith finds his biblically based values to be guides and sources of inspiration that lead him on an authentic journey. The person of traditional faith holds the conviction that his religions teachings direct him toward a rightly-gendered wholeness which allows him to live his life in a manner congruent with his creator’s embodied design.

This wholeness is satisfying, experiential, and deeply integrated into the person’s being. It is achieved not by suppression, repression or denial–but by understanding homosexuality within the greater context of a mature wisdom that is integrated into a scientifically accurate psychology.

References

(1) NARTH Committee Response to APA report, September 11, 2009, narth.com.

(2) The Task Force Report of the American Psychological Association, 2009, “Appropriate Therapeutic Responses to Sexual Orientation,” page 2.

(3) APA Press Release, Public Affairs, May/21/2007.

A man walks into the doctor’s office complaining about a pain in his lower back, and worries that he may have to live with the pain for the rest of his life. The doctor says: “Let me see you walk.” The man gets up and walks back and forth in front of the doctor. The doctor say: “Stop. You are slumping over a bit. Bring your shoulders a little further back and lift your chin slightly. Try walking like that.” The man begins walking as the doctor tells him, and suddenly he feels no pain in his lower back. “See,” the doctor says, “you don’t have a back problem, you have a posture problem. If you focus your attention on how you stand and face the world, your back pain won’t give you trouble. ”

The man is amazed and very grateful, and he goes home. A few hours later he feels the back pain again, and his first thought is that the doctor is a fraud. But then notices that he is not walking with his shoulders back and his chin up, and when he does so, suddenly, the nagging pain disappears. Eventually, the man comes to know his body so well that when he feels the pain, he knows that it’s a signal to him that he is out of posture.

Similarly, I often tell my clients: “You don’t have a homosexual problem, you have a ‘posture’ problem. When you stand up and face the world from a different posture, your same-sex attraction will disappear.”