by Joseph Nicolosi, Ph.D.

No one wants to be the bearer of bad news about a group that has suffered discrimination.

Statistics tell us that gay sex is often tied to substance abuse, promiscuity and unsafe sex practices. A significant minority of gay men also participate in sadomasochism, public sex in bathhouses and group sex.

Many people, both gay and straight, become curious about this “dark side of life” and briefly dabble in it. Soon, however, they come to reject such things as degrading, destructive of their integrity as human beings, and “not who I am.” Why, then, do such things maintain an enduring foothold in the gay community?

This phenomenon is not restricted to a fringe of the gay subculture. Even Andrew Sullivan–a Catholic and well-known conservative in the gay movement–defends the “the beauty and mystery and spirituality of sex, even anonymous sex” in his book Love Undetectable.

And in a speech to a gathering of college students, the Rev. Mel White was also reported by Pastoral Care Ministries Newsletter (Spring 2000) to have said that he does not “struggle” with pornography, but uses it. The reverend is the leader of Soulforce, a gay group that pickets Protestant denominational meetings to push for the blessing of same-sex unions.

Writers Gabriel Rotello (author of Sexual Ecology) and Michelangelo Signorile (Life Outside) are both conservatives in the sense that they have spoken out strongly about the dangers of irresponsible sex and sexually transmitted diseases, and have taken rancorous criticism from the gay community’s more radical faction.

Yet when Signorile speaks of the “rauchy, impersonal atmosphere” of sex in public parks and bathrooms, he is careful to note that he, himself, would never judge it:

“There’s nothing morally wrong with this–and I say that as someone who has certainly had my share of hot public sex, beginning when I was a teenager and well into my adulthood.” (1)

Similarly, Gabriel Rotello says he has been maligned for his role as a so-called “moralistic crusader” against unsafe sex. Yet he explains:

“Let me simply say that I have no moral objection to promiscuity, provided it doesn’t lead to massive epidemics of fatal diseases. I enjoyed the ’70’s, I didn’t think there was anything morally wrong with the lifestyle of the baths. I believe that for many people, promiscuity can be meaningful, liberating and fun.” (2)

Taking a Closer Look

When NARTH’s literature describes the dark side of the gay movement, this is not done for the purpose of moralizing or gay bashing. Our primary purpose is to identify and understand a psychological pattern.

Mainstream psychologists are usually too conflicted (or simply uninformed) to acknowledge any pattern or assign any significance to this sexual radicalism.

Indeed, much of the language of psychologists has been purged of evaluative judgment that could explain the meaning and significance of a particular behavior. A 1975 Dictionary of Psychology states that “fetishism, homosexuality, exhibitionism, sadism and masochism are the most common types of perversion.” Now, 25 years later, the word “perversion” is never used for any of those conditions; they are known as “deviations” or “variations.”

Emotional Deficits Become Sexual Fixations

But because homosexuality is deficit-based, the dark side of gay life–characterized by sexual addictions and fixations–keeps stubbornly emerging, in spite of public-relations efforts to submerge it.

Culture Facts, an online publication of Family Research Council, recently reported on a street fair that illustrates this paradox. The fair was sponsored in part by the Human Rights Campaign (HRC) and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force (NGLTF)–two very prominent groups committed to mainstreaming and normalizing homosexuality.

Yet that event featured public whippings, body piercing, public sex, sado-masochism, and public nakedness by parade marchers. Fair booths sold bumper stickers that said, “God masturbates,” and “I Worship Satan,” and merchants peddled studded dog collars and leather whips (not for their dogs). On the sidelines of the public fair, a man dressed as a Catholic nun was strapped to a cross with his buttocks exposed, and onlookers were invited to whip him for a two-dollar donation.

How long can psychologists be in denial about the significance of the dark side, and ignore what it implies about the homosexual condition?

And there’s a matter of even greater concern. How long will psychologists eagerly throw open the door to gay life for every sexually confused teenager?

Endnotes

(1) “Nostalgia Trip,” by Michaelangelo Signorile, The Gay and Lesbian Review, Spring 1998, Volume Five, No. 2, p. 27.

(2) “This is Sexual Ecology,” by Gabriel Rotello, The Gay and Lesbian Review, Spring 1998, Volume Five, No. 2, p. 24.

by Joseph Nicolosi, Ph.D.

All the psychotherapists who join NARTH (now known as The Alliance for Therapeutic Choice and Scientific Integrity) agree on one essential point–that reorientation therapy is ethical, and that it can be effective for clients who seek it. All strongly defend the client’s right to choose his own direction in treatment.

Beyond that point of agreement around which we all rally, there are some differences.

Some take the position that the condition is a developmental disorder–particularly, a gender-identity disorder–which leads to a romantic idealization and sexualization of the qualities that the individual experiences as deficient within himself.

But other therapists disagree. Some prominent members–even some of our Scientific Advisory Committee members–refuse to take a position on the question of pathology.

Massachusetts psychologist Dr. Uriel Meshoulam, for example, believes the therapist should address the subjective problem of the client’s suffering, and not concern himself with the objective question of disorder. “We must allow the person who seeks treatment to define undesirability and unhappiness,” he says.

In an editorial, Dr. Meshoulam explained the reasoning behind this view:

“Psychotherapy is appropriate when applied to unwanted behaviors and unhappy constructions, rather than to so-called abnormal disorders…Preventing a person who is unhappy with his or her construction of self from seeking treatment is…oppressive.

“Many men and women are unhappy with their construction of their sexuality. It is of questionable ethics to try to convince them that they are ‘wrong,’ and try to convert them to the therapist’s way of thinking. Clients who had been greeted with ‘gay-affirmative’ statements from therapists often told me that they felt grossly misunderstood, and despaired over the prospect of having nowhere to go with their problem.

“…I have seen people who enter therapy with a wide range of unhappy constructions and attitudes toward their sexuality. As a result of therapy, many of them learn to redefine themselves and their sexuality, and thus enhance their potential.”

Some other therapists, including our Scientific Advisory Board member Dr. Mark Stern, take the position that homosexuality is not a disorder, but a missed potential–a closing off of a part of oneself and a “saying no” to generativity.

Some prominent practitioners outside of NARTH take an apparent middle ground on this issue. Dr. Robert Spitzer, the psychiatrist known as the architect of the 1973 decision to remove homosexuality from the list of disorders, maintains that homosexuality was not “normalized” when it was removed from the DSM–only that it was no longer categorized as a disorder. He believes this decision was appropriate because the condition is not invariably assoaciated with subjective distress, nor a generalized impairment in social effectiveness or functioning.

At that time he referred to homosexuality as an “irregular” form of sexuality, and more recently, he agreed that when a person has no capacity for heterosexual arousal, “something is not working.”

There is clearly room for practitioners of both persuasions within NARTH, all working together to defend the client’s right to pursue change.

I myself take the view that homosexuality represents a developmental adaptation to trauma, and that it is potentially preventable. I see strong evidence for the classic psychodyamic position that homosexual behavior is rooted in a sense of gender-identity deficit, and representative of a drive to “repair” that deficit. When the underlying emotional needs and identification deficits are addressed, clinical experience has shown me that the unwanted fantasies and behavior diminish, and for many people, there follows an awakening of some degree of heterosexual responsiveness.

Indeed, the debate continues.

by Joseph Nicolosi, Ph.D.

Bem’s E.B.E. theory relies on two ideas characteristic of gay culture: that gender differences are arbitrary and culturally determined, and that society needs to relax its sexual boundaries.

In “Exotic Becomes Erotic: A Developmental Theory of Sexual Orientation,” (Psychological Review 1996, Vol. 103, #2, pp. 320-335) and his upcoming book, Daryl Bem explains the formation of male homosexuality in a six-step sequence of events called E.B.E. theory.

A former philosophy teacher of mine had a saying: “For every complex question there is a simple answer–and it’s usually wrong.”

E.B.E. theory attempts to respond to a complex question with just this sort of simple answer. With its mechanistic emphasis on autonomic arousal, one wonders why the paper was not published instead in the Journal of Neuroanatomy. Bem’s theory explicitly omits any intrapsychic and interpersonal explanations for homosexuality, implying that normal psychosexual development is no more complex or meaningful than stimulus-response mechanism.

He begins with (a) “biological variables,” which predetermine (b) “childhood temperament,” resulting in (c) “gender-inappropriate behavior,” which causes the boy to (d) “feel different from same-sex peers,” which creates within the boy (e) “non-specific autonomic arousal” toward other boys, which is eventually experienced as (f) “erotic/romantic attractions,” as follows:

A. Biological Variables (e.g., genes, prenatal hormones)

B. Childhood Temperaments (e.g., aggression, activity level)

C. Sex-Typical/Atypical Activity & Playmate Preferences (Gender Conformity/Nonconformity)

D. Feeling Different from Opposite/Same-Sex Peers (dissimiliar, unfamiliar, exotic)

E. Nonspecific Autonomic Arousal to Opposite/Same-Sex Peers

F. Erotic/Romantic Attraction to Opposite/Same-Sex Persons (Sexual Orientation)

Thus Bem traces adult sexual orientation to childhood preferences for sex-typical or sex-atypical activities and friendships. Typical children–those who conform to the norm for their gender–grow up feeling different from the opposite sex; thus they will be attracted to the opposite sex in adulthood. On the contrary, children who grow up feeling different from their own sex in childhood will typically grow up homosexual. He cites one study in which 75% of the non-gender-conforming boys grew up to be homosexual or bisexual.

Dr. John Money’s well-known book, The Sissy Boy Syndrome, describes a similar scenario, as does Zucker and Bradley’s Gender Identity Disorder and Psychosexual Problems in Children and Adolescents, reviewed in the August 1996 NARTH Bulletin.

The heart of his theory, as Bem explains, is “the proposition that individuals become erotically or romantically attracted to those who were dissimilar or unfamiliar to them in childhood.” Thus he sees homosexuality as nothing more or less than a biological predisposition to gender nonconformity, which leads to heightened physiological arousal in response to the perceived strangeness of the opposite sex.

I have counseled over 400 men in my work as a clinician specializing in Reparative Therapy® of homosexuality, and I can attest that Bem’s description of the childhood sequence of events is correct– at least superficially. His theory agrees with Reparative Therapy’s primary principle: that we are erotically attracted to what we are not identified with. Indeed, many homosexually-oriented men report the feeling of not having been “one of the boys,” and having been “on the outside looking in” at male activities throughout childhood and adolescence. Most of my clients were all too familiar with their mothers, but could never understand their fathers. Even when they grew to adulthood, men remained mysteries.

But the problem is that Bem is attempting to explain the whole with a part of the whole. This is called reductionism, or as we see in E.B.E. theory, deconstructionism. Bem essentially reduces developmental psychology to a social deconstructionist view of sex, in which the ideas of heterosexuality as normal, and identification with one’s own sex as normal, are deemed to be mere social constructs.

The Missing “How”

Essentially, Bem shifts the entire discourse away from established principles of psychosexual development onto the neurological mechanism of “excitability.” Citing the “well-documented observation that novelty and unfamiliarity heighten arousal,” he assumes autonomic arousal obliterates all other considerations.

He gives no consideration to the boy’s authentic needs for acceptance, affection and approval from members of the same sex, particularly his father and male peers, and his genuine need to experience himself as a boy-like-other-boys. Nowhere is there acknowledgment of the boy’s natural emotional need for attachment and identification. For Bem, even love is reduced to autonomic arousal.

He avoids the expansive vista of family systems research, clinical case histories, self-report from homosexuals transitioning to heterosexuality, and an understanding of the psychotherapeutic change process. He says nothing of the well-established psychodynamic understanding of the process of gender identification, especially through relationship with the same-sex parent (Bieber, 1962; Hatterer, 1970; Kronemeyer, 1970; Mayerson and Lief, 1965); ignores family systems and object-relations theory, and psychoanalytic/oedipal theory (Socarides, 1968); along with the well-documented, poor father-son relationship for the male homosexual (Bieber 1962). He makes no reference to van den Aardweg’s (1985, 1986) deeper understanding of the meaning of same-sex peer relationships. Thus his model dismisses both subjective experience and personal meaning.

With this dismissal, he fails to understand the developmental significance of critical moments in the life of the prehomosexual boy. One such moment was described to me by a 35-year-old client:

“I recall the exact moment I knew I was gay. I was twelve years old and we were taking a shortcut to class. We were walking across the gym and through the locker room, and an older guy was coming out of the shower. He was wet and naked and I thought, Wow!”

I asked the client to again tell me exactly what his experience was. He became very pensive. Then he answered,

“The feeling was, ‘Wow, I wish I was him’.”

As a little boy, this client had been asthmatic and physically frail. Clearly, the “older guy” coming out of the shower was his idealized self–all that he wasn’t, and wished he could be.

Unmet normal developmental needs predispose the boy to the “Wow!” experience, and later, through influences from an increasingly gay-affirming culture, these feelings are interpreted as “Therefore I must be gay.” This shift occurs during the critical erotic transitional phase, when the same-sex attachment needs of the child change into erotic attraction, and identificatory strivings rooted in same-sex emotional deficit begin to feel sexual. When the client recognizes that these attractions actually represent same-sex identification needs, then the healing of homosexuality begins.

Bem says he omits consideration of the deeper developmental meaning of experience because the literature fails to establish a “coherent, experienced-based developmental theory of sexual orientation.” The problem, he says, is in psychology’s past attempts to “empirically measure experience.” (He will make up for this lack, he says, by finding a measure for a neurological concomitant of experience.)

On a Shaky Foundation: Bell and Weinberg

Bem builds his model almost exclusively on Bell, Weinberg amd Hammersmith’s Sexual Preference: Its Development in Men and Women (1981), a study which claims to “once and for all” debunk the developmental and family factors linked to homosexuality. This study analyzes recollections of family experiences through a statistical procedure called path analysis. Originally designed for use by the hard sciences, path analysis has been called inappropriate for use in the social sciences (Brandstadter and Bernitzke, 1976).

Many writers have criticized the conclusions drawn by the Bell study (Gagnon, 1981, Reiss, 1982, DeLamater). In a review of the Bell study in Contemporary Sociology, Ira Reiss comments:

“It is hard to see how this study can ‘once and for all’ settle our thinking…the tendency to underplay the importance of the predictor variables, and thereby imply strong rejection of previous theories, is pervasive…there is a serious lack of theoretical development in handling the data…Overall, the book does not impress one as a development of theoretical insights into sexual preferences, but rather as an attempt to play down aspects of psychoanalytic and other, older views [emphasis added].”

Why did Bell, et al. so resoundingly dismiss the family data? Some sources see a desire to interpret the data for gay-advocacy purposes. In Gender Identity Disorder and Psychological Problems in Children and Adolescents, Zucker (1995) states:

“… we should note that the Bell, et al. study will ultimately have to be understood in a broader context–that of the sexual politics of our time.” (p. 240) “… [T]heir interpretation of their data was clearly colored by political correctness…If, in fact aspects of their family interaction and relationship data showed a departure from an ideal of optimal functioning in homosexual men, Bell, et al. (1981) … [tended] … to minimize the observed significant effects.

“…Influenced by the zeitgeist … [they] chose to interpret their data as showing that the glass was half empty, not half full” (p. 241).

Love as Fetish

Bem then reaches back for further supportive evidence of his E.B.E. theory to an 1887 reference explaining that “strong and vivid emotion” becomes associated with feelings of “love.” He quotes a literary piece in which a man, trying to woo a woman, did so by killing her pet pigeons. Her intense arousal at the sight of the suffering pigeons contributed to her falling in love with her suitor.

He reaches back further yet to a first-century Roman handbook called “The Art of Love.” In this handbook, Ovid advises any man who is interested in sexual seduction to take the woman to a gladiatorial tournament, where she would be more easily aroused with passion.

According to this “excitability” model, both homosexuality and heterosexuality are reduced to the psychology of the fetish. Fear, anger, hatred, sadism, masochism, romantic passion, enduring love–for Bem, all spring from the same source in mechanism.

The fetishes, in fact, he sees not as disorders, but as reflections of arbitrary cultural prejudices. Physical attributes not regarded by a culture as beautiful (feet, for example), when eroticized by individuals within that culture, cause that person to be (in Bem’s view) unfairly burdened by being called fetishists. It seems to him that heterosexual men from our culture who love women’s breasts should themselves be considered to have a fetish. But the problem with this deconstructionist view is that, as any clinician knows, the compelling drive and compulsive quality of the paraphilia is not the same as the heterosexual man’s normal attraction to female anatomy. Further, he reduces all normal sexual attraction to the level of a fetish. Perhaps for Bem, love itself is mere fetish.

While conceding that he doesn’t yet understand the specifics of precisely how exotic becomes erotic, he is quite satisfied to conclude:

“[I]t is sufficient to know that autonomic arousal, regardless of its source or affective tone, can subsequently be experienced cognitively, emotionally, and physiologically as erotic/romantic attraction. At that point, it is erotic/romantic attraction.” (p. 326)

E.B.E. theory is an attempt to contribute to a “different but equal” developmental model of sexual orientation, treating homosexuality and heterosexuality as the same phenomenon.

To accommodate his simplistic neurological model of the person, Bem must follow with a simplistic understanding of culture. He deems culture largely responsible for sexual object-choice, due to its “social constrictions of gender,” and repeatedly bemoans our “gender-polarizing culture”–but offers no non-gender-polarizing culture in contrast.

From the point of view of the gay community, Bem’s model makes an important contribution in that it describes a model of homosexual development which is non-pathological. (After thirty years of marriage and two children, he recently “came out” as gay.) “Indeed,” he says, “the gay community should be happy with E.B.E. theory because it views heterosexuality as no more biologically natural than homosexuality.”{1}

But by viewing homosexuality as essentially the same phenomenon as homosexuality, and by putting sexual orientation and romantic love on a par with fetishes, he disregards the larger significance of human relationships. Refusing to grant that heterosexuality is the mature outcome of psychosexual development, he contradicts a simple–and I believe accurate–working definition of the term “normal”: “that which functions according to its design.{2}

In support of this philosophy, he quotes his (apparently former) wife Sandra as she rather obscurely describes her apparent pansexuality:

“I am not now–and never have been–a ‘heterosexual,’ but neither have I been a ‘lesbian’ or a ‘bisexual’ …. The sex-of-partner dimension implicit in the three categories … seems irrelevant to my own particular pattern of erotic attraction and sexual experiences.

“Although some of the (very few) individuals to whom I have been attracted … have been men and some have been women, what those individuals have in common has nothing to do with either their biological sex, or mine–from which I conclude, not that I am attracted to both sexes, but that my sexuality is organized around dimensions other than sex.” (p.vii)

A Society Where Everyone Could Be Everyone Else’s Lover

Elaborating on his wife’s personal revelation, Daryl Bem proceeds to define his own utopian society. He describes a world often championed by gay theorists–one where everyone would potentially be everyone else’s lover, and gender would be insignificant. He envisions a…

“non-gender-polarizing culture that [does] not systematically estrange its children from either opposite sex, or same sex peers. Such children would not grow up to be asexual; rather, their erotic and romantic preferences would simply crystallize around a more diverse and idiosyncratic variety of attributes. Gentlemen might still prefer blondes, but some of those gentlemen (and some ladies) would prefer blondes of any sex. In the final deconstruction, then, EBE theory reduces to but one ‘essential’ principle: Exotic becomes erotic” (p. 332).

In the end, Bem is so taken by his own radical deconstructionist theory that he sees it as the only “given” in the development of sexual orientation. Nothing else is normal and necessary for healthy psychosexual development. Delighted by the elegance of his model, he concludes:

“That’s it. Everything else is cultural overlay, including the concept of sexual orientation itself.” (p. 331)

Endnotes

{1}Bem, D. Cornell Chronicle, August 29, 1996, p. 8.

{2}King, C. (1945). “The meaning of normal,” Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine, 18, 493-501.

Bibliography

Bell, A., Weinberg, M., Hammersmith, S., (1981). Sexual Preference: Its Development in Men and Women. Indiana University Press: Bloomington, IL.

Bieber, I. et al. (1962). Homosexuality: A Psychoanalytic Study of Male Homosexuals. New York: Basic Books.

Brandtstadter, J. and Bernitzke, F., “The Technique of Path-Analysis: A Contribution to the Problem of Experimental Construction of Causal Models.” Psychologische-Beitrage, 1976, Vol. 18(1), pp. 12-34.

DeLamater, John, “Origins of Sexual Preference,” Book Review in Science, Vol. 215, March 5, 1982, pp. 1229-1230.

Gagnon, John H., “Searching for the Childhood of Eros,” New York Times Book Review, Vol. 86, Dec. 13, 1981, p. 10, 37.

Hatterer, L. (1970). Changing Homosexuality in the Male. New York: McGraw Hill Book Co.

Kronemeyer, R. (1980). Overcoming Homosexuality. New York: MacMillan.

Mayerson, P. and Lief, H. (1965). Psychotherapy of homosexuals: A follow-up study. In Marmor J. (Ed.), Sexual Inversion: The Multiple Roots of Homosexuality. New York: Basic Books.

Reiss, Ira L., “Sex and Gender: Book Review,” Contemporary Sociology, Vol. 11, No. 4, July 1982, pp. 455-456.

Socarides, C.W. (1968). The Overt Homosexual. New York: Grune and Stratton.

van den Aardweg, G. (1985). Homosexuality and Hope: A Psychologist Talks about Treatment and Change. Ann Arbor, MI: Servant Books.

———————(1986). On the Origins and Treatment of Homosexuality: A Psychoanalytic Reinterpretation. Westport, CT: Praeger.

Zucker, K. J., Bradley, S. J. (1995). Gender Identity Disorder and Psychological Problems in Children and Adolescents. New York: Guilford Press.

by Joseph Nicolosi, Ph.D. and Dale O’Leary

This article appeared in 1999 in the NARTH (National Association of Research and Therapy of Homosexuality) Bulletin. It reports on a study published by the American Psychological Association. Although it is not recent news, the subject remains quite relevant today.

Deconstructionists argue that distinctions between the genders are arbitrary and political. Now, the same argument is being advanced by man-boy love advocates about the distinction between the generations.

An article published last summer in the American Psychological Association’s Psychological Bulletin has drawn a recent firestorm of criticism. Talk show hosts and congressmen are calling for investigations. The outrage has focused on the authors’ conclusion, based on their analysis of child-molestation studies, that “the negative effects [of sexual abuse] were neither pervasive nor typically intense.”

The article was entitled “A Meta-analytic Examination of Assumed Properties of Child Sexual Abuse Using College Samples.”

APA spokeswoman Rhea Faberman defended publication of the article as part of the scientific work of the organization, saying, “We try to create a lot of dialogue.” She labeled “ridiculous” the claim of radio talk-show host Dr. Laura Schlessinger that publication of the article and the attempt to normalize pedophilia were in any way related.

Contrary to Ms. Faberman’s assertion, however:

- There is a real and growing movement to legitimize and also legalize sexual relations between boys aged 10 to 16 and adult males;

- Robert Bauserman, one of the authors of the article, has associated himself with the pedophilia movement through a previous article;

- The movement’s strategy is to promote the “objective” study of child/adult sex, free of moral considerations;

- The APA should have known this before they published the article.

Those who are interested in legalizing sexual relations between adults and children want to change the parameters of the discussion from the “absolutist” moral position, to the “relative” position that it can sometimes be beneficial. The A.P.A. article furthered exactly this position.

Deconstructionists have argued–with some success–that distinctions between the genders are arbitrary and politically motivated. Now, the same argument is being advanced about the distinction between the generations.

In a recent lead article of the Journal of Homosexuality (1), for example, Harris Mirkin says the “sexually privileged” have disadvantaged the pedophile through sheer political force in the same way that blacks were disadvantaged by whites before the civil-rights movement.

The Movement to Legitimize Pedophilia

In 1981, Dr. Theo Sandfort, co-director of the research program of the Department of Gay and Lesbian Studies at the University of Utrecht, Netherlands, interviewed 25 boys aged 10 to 16 who were currently involved in sexual relationships with adult men. The interviews took place in the homes of the men.

According to Sandfort, “For virtually all the boys … the sexual contact itself was experienced positively…” Could an adult-child sexual contact, then, truly be called positive for the child? Based on the research presented, Sandfort answered that question in the affirmative.

The study was severely criticized by experts in the field of child sexual abuse. Dr. David Mrazek, co-editor of Sexually Abused Children and Their Families, attacked the Sandfort research as unethical, saying:

“In this study, the researchers joined with members of the National Pedophile Workshop to ‘study’ the boys who were the sexual ‘partners’ of its members … there is no evidence that human subject safeguards were a paramount concern. However, there is ample evidence that the study was politically motivated to ‘reform’ legislation.

“These researchers knowingly colluded with the perpetuation of secret illegal activity … In the majority of cases, these boys’ parents were unaware of these sexual activities with adult men, and the researchers contributed to this deception by their action.”

Child sexual-abuse expert Dr. David Finkelhor also criticized the Sandfort research, pointing to the numerous studies which show adult-child sexual contact as a predictor of later depression, suicidal behavior, dissociative disorders, alcohol and drug abuse, and sexual problems.

Dr. Finkelhor strongly defended laws against child/adult sex, saying that many of those now-grown children are very active in lobbying for such protection.

In 1990, the campaign to legalize man-boy sex was furthered by the publication of a two-issue special of the Journal on Homosexuality, reissued as Male Intergenerational Intimacy: Historical, Socio-Psychological, and Legal Perspectives.

This volume provided devastating information on the way psychologically immature pedophile men use vulnerable boys who are starved for adult nurturance and protection.

In the forward, Gunter Schmidt decries discrimination against and persecution of pedophiles, and describes

“successful pedophile relationships which help and encourage the child, even though the child often agrees to sex while really seeking comfort and affection. These are often emotionally deprived, deeply lonely, socially isolated children who seek, as it were, a refuge in an adult’s love and for whom, because of their misery, see it as a stroke of luck to have found such an ‘enormously nurturant relationship’.”

There is another deeply disturbing article in the volume, revealingly titled, “The Main Thing is Being Wanted: Some Case Studies on Adult Sexual Experiences with Children.” In it, pedophiles reveal their need to find a child who will satisfy their desire for uncritical affirmation and a lost youth. One of the men justifies his activity as a search for love, and complains that: “Although I’ve had physical relationships with probably, I don’t know, maybe a hundred or more boys over the years, I can only point to four or five true relationships over that time.”

The volume also contains an introductory article which decries society’s anti-pedophile sentiment. The authors complain about the difficulty studying man-boy relationships in “an objective way,” and they hope the social sciences will adopt a broader approach which could lead to understanding of the “diversity and possible benefits of intergenerational intimacy.”

Bauserman Defends Sandfort’s Research

The same volume contains an article by Robert Bauserman-co-author of the A.P.A. study–which complains that objective research is impossible in a social climate that condemns man-boy sexual relationships. Bauserman decries the prevailing ideology that labels all boys as “victims” and all adult pedophiles as “perpetrators.” He attacks researchers Mzarek and Finkelhor as being driven by a “particular set of beliefs about adult-juvenile sex.” Bauserman looks for a new “scientific objectivity,” with the explicit call for research that will challenge the social-moral taboo against adult/child sex. The meta-analysis which he co-authored, and which the American Psychological Association published, can be seen as Bauserman’s follow-up to his Journal of Homosexuality article.

More Recent Defenses of Pedophilia

Harris Mirkin recently wrote a lead article in the Journal of Homosexuality entitled “The Pattern of Sexual Politics: Feminism, Homosexuality and Pedophilia.” Using social-constructionist theory, he argues that the concept of child molestation is a “culture- and class-specific creation” which can and should be changed.

He likens the battle for the legalization of pedophilia to the battles for women’s rights, homosexual rights, and even the civil rights of blacks.

He sees the hoped-for shift as taking place in two stages. During the first stage, the opponents of pedophilia control the debate by insisting that the issue is non-negotiable–while using psychological and moral categories to silence all discussion.

But in the second stage, Mirkin says, the discussion must move on to such issues as the “right” of children to have and enjoy sex.

If this paradigm shift could be accomplished, the issue would move from the moral to the political arena, and therefore become open to negotiation. For example, rather than decrying sexual abuse, lawmakers would be forced to argue about when and under what conditions adult/child sex could be accepted. Once the issues becomes “discussible,” it would only be a matter of time before the public would begin to view pedophilia as another sexual orientation, and not a choice for the pedophile.

The response to the APA article shows that for the present, social opposition to pedophilia continues to be strong. Finkelhor’s response to Bauserman, which was included in Male Intergenerational Intimacy, explains why:

“Some types of social relationships violate deeply held values and principles in our culture about equality and self-determination. Sex between adults and children is one of them. Evidence that certain children have positive experiences does not challenge these values, which have deep roots in our worldview.”

To pedophile advocates, any discussion of the benefits of child-adult sex is a victory. The APA should have understood this, should have known about Bauserman’s connections, and should have been well aware of–and vocally resistent to–the growing movement to legalize pedophilia.

Endnote

Mirkin, Harris, “The Pattern of Sexual Politics: Feminism, Homosexuality and Pedophilia,” Journal of Homosexuality vol. 37(2), 1999, p. 1-24.

by Joseph Nicolosi, Ph.D. and Linda Ames Nicolosi

A February 2001 article published in The American Psychologist critiqued the traditionalist view of the man as head of the household and family protector. NARTH President Joseph Nicolosi and his wife, Linda Ames Nicolosi, submitted the following Commentary to the journal:

In your lead article of the last issue of the American Psychologist (1), the authors criticize the “benevolent sexism” and “chivalrous ideology” in a marriage where the husband serves as the protector and provider.

Given that the authors’ radical feminist view is at odds with a significant portion of American society, it is surprising indeed that there is so little resistance to it in the pages of this journal. We see little objection–in this journal or others–to the relentless deconstruction of the traditional family, and to the related assumption that children do just as well, if not better, in nontraditional families.

Perhaps this view is so prevalent in intellectual circles because we Americans love democracy so much–along with its cherished individualism and equality–that we easily tend to slip down the slippery slope into radical egalitarianism. Radical egalitarianism, some philosophers have noted, leads to a denial of the foundational social distinctions of gender, generation, and hierarchy.(2)

But when gender distinctions are denied, and the subtle, hierarchical distinctions of traditional marriage are deemed merely laughable, there is reason for concern for the continuation of the foundational institution of marriage, upon which democracy itself depends.

As Stanley Kurtz of the Hudson Institute has noted, (3) the success of marriage actually seems to depend on gender distinctions–particularly, the innate complementarity of the sexes, although “even to mention it [complementarity] these days is to invite ridicule.” Male-female physical and emotional complementarity is, Kurtz astutely observes, biologically-based and thus “not about to disappear.” Women help to domesticate the man’s typically more aggressive, sexual and risk-taking nature.

Innate gender differences may help to explain why gay male relationships, for example, in contrast to heterosexual marriage, characteristically turn out to be “open,” while lesbian relationships are more often socially exclusive and tend to be possessive. Neither of the latter two types of relationships possesses the strength inherent in gender complementarity.

Does a man’s protectiveness toward his family translate into anything like “sexism,” or worse, a form of despotism? Perhaps quite the opposite; in fact, one very important factor that works in favor of marriage, as Kurtz notes, is a man’s sense that his home is his “castle” and he its “king.” Even so, the reality, he observes, is that “a rough sort of equality” has always lain hidden in the reality of a husband-wife relationship. But still, “what the Promise Keepers has the audacity to say out loud about a man’s authority within the marriage bond remains, in subtler form, the formula of heterosexual marital success.”

While the authors of the American Psychologist article would obliterate gender distinctions, the distinction between the generations is now also slowly deteriorating. Thus we now see arguments being made in favor of “intergenerational intimacy”–a euphemism for man-boy sex–which are published in the Journal of Homosexuality. That journal has argued that children are an oppressed minority who possess a natural right to their sexual autonomy.

The next frontier is the obliteration of the distinction between the species–a project of the animal-rights movement and of those who question whether human life is indeed any more sacred than that of animals.

Where, we are asking, is the intellectual resistance to these movements? Other than within journals of religion and public policy like First Things and Commentary, its intellectual opponents have largely fallen silent.

Some of this silence can be attributed to the powerful “censoring role” of the media which prefers to promote its favorite causes; some, we believe, to the fact that a small group of deeply committed idealogues (particularly, radical feminists and gay activists) can impose social and career costs on their adversaries.

“But one also senses,” says Kurtz (and we agree), “that the silencing of the majority would never have been possible were the majority itself more certain of its ground.”

Endnotes

(1) “An Ambivalent Alliance: Hostile and Benevolent Sexism as Complementary Justifications for Gender Inequality,” The American Psychologist, February 2001, p. 3.

(2) Weaver, Richard, Ideas Have Consequences. Chicago, Ill.: U. of Chicago Press, 1948.

(3) Kurtz, Stanley, “What is Wrong with Gay Marriage,” Commentary, September 2000, pp. 35-41.

by Joseph Nicolosi, Ph.D.

We live in a culture where tolerance, diversity, and the right to define oneself are valued very highly. Today, people who want to live their lives as “gay” are free to do so. That’s their right.

But There’s Another Sexual Minority I’d Like To Tell You About.

These are the men and women who — despite having some homosexual feelings — believe that humanity was designed to be heterosexual.

Homosexuality will never define “who they really are.”

The major professional groups — the American Psychological Association and American Psychiatric Association — (the “APA’s”) — have abandoned these people. Today, gay activists speak for the APA’s on subjects related to homosexuality.

In contrast, “ex-gays” — the sexual minority I have been talking about — are simply forgotten.

Because they have listened only to gay activists, not ex-gays, the APA’s have promoted the myth that people are “born homosexual.” They’ve also promoted the myth that if you have homosexual attractions, that gay is simply “who you are” — and that claiming another lifestyle or identity is a betrayal of one’s “true nature.”

Also, the APA’s have abandoned the age-old understanding that children need BOTH a mother AND a father.

And they’ve promoted the myth that homosexuality is just like heterosexuality, except for the gender of the partner.

All of these ideas are … just myths.

How could this be true? I invite you to read the material posted on this web site.

In everything we write, we have worked hard to be scientifically accurate, and also to be fair and respectful in representing the ideas those who disagree with us. Because “tolerance, diversity and inclusion” are essential guidelines for both sides in any respectful debate.

That is why I am standing up for what I believe.

by Joseph Nicolosi, Ph.D.

I would like to propose a socio-analytic view of the formation of gay identity. This view is based upon the perspective I have gained from the clinical treatment of over 400 homosexually-oriented men during eighteen years as a practicing psychologist.

“The gay identity” has been portrayed as a civil-rights and self-determination issue. We Americans, who love freedom, have loved it too much and have lost our moorings. Our most influential institutions–professional psychology and psychiatry, churches, the education establishment, and the media–have fallen to the gay deception. Because gay is, I am convinced, a self-deceptive identity.

“Gay” is Not “Homosexual”

First, let’s begin with the understanding that I will not be speaking about the person who struggles with same-sex attraction, but rather the gay-identified person–which is to say, that person who is ego-invested and personally identified with the idea that homosexual behavior is as normal and natural as heterosexual behavior.

Secondly, I wish to clarify my belief that there is no such thing as a gay person. Gay is a fictitious identity seized upon by an individual to resolve painful emotional challenges. The man who recognizes that he has a homosexual problem and struggles to overcome it is not “gay.” He is, simply, “homosexual.”

To believe in the concept of a gay identity as valid, a person must necessarily deny significant aspects of human reality. The foundation typically begins with a significant denial of human reality during early childhood.

I’d like to propose a three-step, psycho-social model for the development of a gay identity–first, beginning with the prehomosexual child and his gender distortions; second, with his later assimilation into the gay counterculture, which fosters those same distortions about self and humanity; and finally, concluding by describing how the gay community’s self-deception has expanded into the further deception of a large portion of society.

Early Gender Identity

Let’s begin with the child. At a critical developmental period called the gender-identity phase, the child discovers that the world is divided between male and female. Which one is he going to be? He is personally challenged to assume maleness or femaleness — “Am I a boy? Or am I a girl?” We’ll be talking primarily about boys, because there are some more complex variations for the lesbian.

Confronted with the reality of a gendered world, male and female, and forced to make a choice, the child may first resort to an avoidance strategy–regressing into an androgynous phase: “I need not relinquish the benefits of either sex. I can be both male and female.” However, reality pushes in and language now enters, and he hears “he” and “she,” and “his” and “hers.”

Both sexes are first identified with the mother, the “first love object”–but the boy has the additional developmental task of disidentifying from the mother to move on to the father. We must make no mistake about this: masculinity, as Robert Stoller said, is an achievement. The child–especially the boy–has to work not only for the acquisition of identity, but for the acquisition of gender. Every culture that has ever survived understands this matter of the “achievement” of gender, and will support and assist the boy through rites of passage and male initiation.

Increasingly today, we are abandoning support of our boys’ formation of masculine identity; particularly the support needed from the parents. For the boy, the father is most significant in the identification process. If he is warm and receptive and inviting, the boy will disidentify with mother and bond with father to fulfill his natural masculine strings. If the father is cold, detached, harsh, or even simply disinterested, the boy may reach out, but eventually will feel hurt and discouraged and surrender his natural masculine strivings, returning to his mother.

There is no convincing scientific evidence of a “gay gene,” but certain boys do seem especially vulnerable to homosexual development. Clinical experience tells us that the boy who is sensitive, passive, gentle, and esthetically oriented may be most susceptible to retreat from the developmental challenge to gender-identify with his father. A tougher, bolder, thicker-skinned son may well succeed in pushing through an emotional barrier. The sensitive son seems to decide, “I can’t be male, but I’m not completely female either; so I will remain in my own androgynous world, my secret place of fantasy.”

And, as we shall see, this quality of androgynous fantasy endures into adulthood: in fact, it is a fundamental feature of gay culture. This fantasy contains within it, not only the narcissistic refusal to identify with a gendered culture, but also the refusal to identify with the human biological reality upon which our gendered society is based. In fact, gender–a core feature of personal identity–is central to the way we relate to ourselves and others. It is also a central pathway through which we grow to maturity.

A host of studies confirm the correlation between childhood gender nonconformity, which is suggestive of gender-identity confusion, and later homosexuality. Not all homosexuality develops this way, but this is a common developmental pathway. We hear echoes of this theme over and over in gay literature–the repeated story of the prehomosexual boy who is isolated and “on the outs” from male friends, feeling different, insecure in his masculinity and alone, disenfranchised from father, and retreating back to mother. Camille Paglia, a lesbian activist, says she struggled with a “massive gender dysfunction” throughout childhood. Andrew Sullivan, the gay author of Virtually Normal, was asked by a young classmate, “Are you a girl or a boy in there?”

Because gender was such a source of pain in childhood, the annihilation of gender differences is, not surprisingly, a central demand of gay culture. Gays often call their attitude “an indifference to gender.” Daryl Bem, a gay psychologist, describes his version of utopian society as a “non-gender-polarizing culture” in which everyone would potentially be anyone else’s lover. Other gay writers insist on an “end to the gender system.”

Detachment from Self and Others

So we see that the man who accepts the gay label in adulthood, has typically spent much of his childhood emotionally disconnected from people, particularly his male peers and his father. He also was likely to assume a false, rigid “good little boy” role within the family.

One of my clients said, “I was a non-entity. I didn’t have a place to feel.” Another man said, “I always acted out other people’s scripts for me. I was an actor in other people’s plays.”

One client said, “My parents watched me grow up”; and hearing this, another client added, “I watched myself grow up.” Do you hear that quality of detachment from self? — “I watched myself grow up.” No wonder the pre-homosexual boy is often interested in theatre and acting—” Life is theatre. We are all actors. Can’t reality just be what we wish it to be?”

In the absence of an authentic identity, it is easy to self-reinvent. Oscar Wilde (who probably was the first person to give a face to “gay”), said, “Naturalness is just another pose.”

Without domestic emotional bonds to ground him in organic identity, the gay man is plastic. He is the transformist, a Victor-Victoria, or the character from “La Cage Aux Folles.” He is pretender, jokester–what French psychoanalyst Chasseguet-Smirgel calls “the imposter.” He is what the gay, Jungian psychotherapist Robert Hopcke calls “the outsider, the trickster, the androgyne–the person who breaks the boundaries in our society.”

Freud said, “The father is the reality principle.” Father represents the transition from the blissful mother-child, symbiotic relationship into harsh reality. But the pre-homosexual boy says to himself, “If my father makes me unimportant, I make him unimportant. If he rejects me, I reject him and all that he represents.” Here we see the infantile power of “no” — “Father has nothing to teach me. His power to procreate and affect the world are nothing compared to my fantasy world. What he accomplishes, I can dream. Dream and reality are the same.”

Rather than striving to find his own masculine, procreative power…moving out into the world, trying to impact it…he chooses, instead, to stay in the dreamy, good-little-boy role. Detached, not only from father and other boys, but from maleness and his own male body–including the first symbol of masculinity, his own penis–an object alien even to himself. He will later try to find healing through another man’s penis. Because that is what homosexual behavior is: the search for the lost masculine self.

Since anatomically grounded gender is a core feature of individual identity, the homosexual has not so much a sexual problem, as an identity problem. He has a sense of not being a part of other people’s lives. Thus it follows that narcissism and preoccupation with self are commonly observed in male homosexuals.

The Identity Search is Felt as Homoeroticism

Now in his early teenage years, unconscious drives to fill this emotional vacuum–to want to connect with his maleness–are felt as homoerotic desires. The next stage will be entry into the gay world.

Then for the first time in his life, this lonely, alienated young man meets (through gay romance novels from the library, television personalities, or internet chat rooms) people who share the same feelings. But he gets more than empathy: along with the empathy comes an entire package of new ideas and concepts about sex, gender, human relationships, anatomical relationships, and personal destiny.

Next he experiences that heady, euphoric, pseudo-rite-of-passage called “coming out of the closet.” It is just one more constructed role to distract him from the deeper, more painful issue of self-identity. Gay identity is not “discovered” as if it existed a priori as a natural trait. Rather, it is a culturally approved process of self-reinvention by a group of people in order to mask their collective emotional hurts. This bogus claim to have finally found one’s authentic identity through gayness is perhaps the most dangerous of all the false roles attempted by the young person seeking identity and belonging. At this point, he has gone from compliant, “good little boy” of childhood, to sexual outlaw. One of the benefits of membership in the gay subculture is the support and reinforcement he receives for reverting to fantasy as a method of problem solving.

The Fantasy Option

He is now able to do collectively what he did alone as a child: when reality is painful, choose the fantasy option. “I have merely to redefine myself and redefine the world. If others won’t play my game, I’ll charm and manipulate them. If that doesn’t work, I’ll have a temper tantrum.”

For that lonely child, what awesome benefits of membership he receives by assuming the gay self-label! He receives unlimited sex and unlimited power by turning reality on its head. He enjoys vindication of early childhood hurts. Plus as an added bonus, he gets to reject his rejecting father and similarly, the Judeo-Christian Father-God who separated good from bad, right from wrong, truth from deception. Oscar Wilde said, “Morality is simply an attitude we adopt toward people whom we personally dislike.”

Next, we move on to look at the third level: “How has this group of hurt boys and girls–now known in adulthood as the gay community–managed to promote their make-believe liberation not only to popular culture but to legislators, public-policy makers, universities, and churches?

There are a number of ways, but three such avenues stand out for mention.

The first is the civil-rights movement, probably the single most influential force in forming the collective consciousness of American society in this century. Gay apologists have used authentic rights issues as a wedge to promote their redefinition of human sexuality and, essentially, human nature. And one powerful tool that has been used time and time again is the Coming Out Story. It is that same generic story that has been repeated almost verbatim for thirty years now–from the committee rooms of the American Psychiatric Association in 1973, to the Oprah Winfrey Show.

I have seen religious clergy warmly applauding coming-out stories. And why not? Because “finding oneself” and “being who one really is” are popular late-twentieth-century themes which have a heroic and attractive ring to them. Certainly the person telling the story is sincere. He means what he says, but the audience rarely looks beyond his words to understand his coming-out in the larger context.

A second factor is that sexuality itself is in crisis, with fundamental changes now taking place in our definition of family, community, procreation, marriage, and gender. All of these changes have occurred in the service of an individual’s right to pursue sexual pleasure. But historically, although the gay- rights movement followed along on the coattails of the civil-rights movement, it continues to draw its ideological power from the sexual-liberation movement.

There is at this time, a cultural vulnerability to gay-lib rhetoric. Chasseguet-Smirgel says the “pervert” (in the traditional psychoanalytic sense of the term) confuses two essential human realities: the distinction between the generations, and between the sexes. In gay ideology, we see just this sort of obliteration of differences.

Similarly, Midge Decter tells us we are a culture that treats our children like adults (we have only to look at sex education in elementary school), at the same time that adults are acting like children.

Ours is a consumer-oriented society, and consumer products shape our views of ourselves. Marketing strategists are all-too-ready to target consumer groups. Gay couples are called “DINKS”–dual income, no kids. And that means expendable income. Merchants have always been ready to cater to gay clientele, and merchant-solicitors have given the gay community the face of legitimacy. Today, nearly every major corporation offers services specially tailored to homosexuals–corporations like AT&T, Hyatt House, Seagrams, Apple Computer, Time-Warner, and American Express. Alcohol and cigarettes are popular gay items. We see gay resorts, gay cruises, gay theatre, gay film festivals. Gay magazines, movies and fiction give face and theme to individuals whose essential problem is identity and belonging. Luxury items–jewelry, fashions, furnishings, and cosmetics are ready to soothe, flatter, and gratify a hurting minority. But beyond material reassurance, these luxury items equate gay identity with economic success– “The gay life is the good life.”

Yet “gay” remains a counter-identity, a negative. By that I mean it gets its psychic energy by “what I am not,” and is an infantile refusal to accept reality. Through justification offered through today’s liberal-arts education, it is easily rationalized by the arguments of deconstructionism.

Deconstructionism and the gay agenda are perfectly compatible. They conform to a number of corresponding, modern movements, including the trend against “species-ism”–promoting the idea that man must lay no claim to being above animals. Animal liberationist and founder of PETA Ingrid Newkirk says that “a rat… is a pig…is a dog…is a boy.”

There are also movements to break down the barriers between the generations, evidenced by psychiatry’s recent loosening of the diagnostic definition of pedophilia, and the publishing of the double Journal of Homosexuality issue, “Male Intergenerational Love” (an apologia for pedophilia). There are popular movements (primarily gay and feminist) to deny any mental and emotional differences between the sexes, and–even more alarmingly–nature-worship movements which resymbolize the instincts as sacred.

The founder of the deconstructionist movement is Michel Foucault, a gay man whose philosophical views emerged out of his own personal struggle with homosexuality. Foucault actally had the outrageous plan to deconstruct the distinction between life and death; in his later years, he was obsessed with the idea of simultaneously experiencing death and orgasm. He eventually succeeded, as Charles Socarides says, in “deconstructing himself” (he died of AIDS in a sanitarium).

And so through deconstructionism we see animal confused with human, sacred confused with profane, adult confused with child, male confused with female, and life confused with death — all of these, traditionally the most profound of distinctions and separations, are now under siege through modern deconstructionism.

“Gay” in Film Mythology

In the recent animated Disney film, the Lion King, we see the age-old generational link in the proud and loving relationship between the father Mufasa, king of the lions, and his little son Simba, the future king. They live in the balanced, ordered world of the lion kingdom. Now we also have this other character Scar, the brooding, resentful brother of the king, who lives his life on the outside and is full of envy and anger. It has been argued that Scar is a gay figure.

In the film, it is Scar who ruptures the father-son link between the generations. He kills the Lion King while aligning himself with a scavenger pack of hyenas. Thus Scar turns the ordered lion kingdom into chaos and ruin. But before all this occurs, we hear a brief, light-hearted dialogue between the young male cub, Simba, and his uncle Scar.

Laughingly Simba says, “Uncle Scar, you’re weird.”

Meanfully, Scar replies, “You have no idea.”

The Way Out

And so we have seen that gay is a compromise identity seized upon by an individual, and increasingly supported by our society, in order to resolve emotional conflicts. It is a collective illusion; truly, “the gay deception.” But I have seen more men than I can count in the process of struggle, growth and change. The struggle is a soul-searing one, challenging, as it must, a false identity rooted in one’s earliest years.

As adults, these strugglers have looked into the gay lifestyle and returned disillusioned by what they saw. Rather than wage war against the natural order of society, they have chosen to take up the challenge of an interior struggle. This is, I am convinced, the only true solution to an age-old identity problem.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Chasseguet-Smirgel, Jeannine (1984). Creativity and Perversion. New York, New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Disney Press (1994). The Lion King. New York, New York.

Miller, James E. (1993). The Passion of Michel Foucault. New York, New York: Simon & Schuster.

by Joseph Nicolosi, Ph.D.

IMAGINE: A class-action suit against the American Psychiatric and Psychological Associations–initiated by homosexual strugglers and their families because of the A.P.A.s’ failure to disclose that homosexuality is a treatable condition.

IMAGINE: Men and women testifying that:

Based upon the APAs’ policy recommendations, mental-health counselors had neglected to tell them about all available treatment options.

At a very vulnerable time in their lives, they were advised–without any conclusive scientific evidence–that they were “born gay,” or “had a gay gene.”

They were told to surrender their hope of ever living a traditional family life of spouse and children, and “work through their internalized homophobia” so they could learn to enjoy something they believed was incompatible with their core being.

They were not properly informed that acceptance of a gay identity would lead to greater risk for anxiety, depression, low self-esteem, loneliness, suicide attempts, failed relationships, drug use, alcohol abuse, tobacco use, and addiction to unhealthy (exotic) sexual practices, as well as STD’S and AIDS.

IMAGINE: Attorneys for the plaintiffs showing:

In many cases, gay-affirmative therapy (the psychotherapist’s advice to accept a gay identity) is not appropriate for the patient, and is induced through coercion.

Public-policy statements by the APAs’ regarding the “normalcy” of homosexuality are not and cannot be scientifically neutral conclusions, but are influenced by the social-political philosophy of the time.

Interpretation of the scientific data has been skewed to support the APAs’ favored social philosophy.

The APAs’ systemical withholding of relevant information has restricted the patient’s right to choose from among all reasonable treatment options.

The APAs’ have shown callous disregard for cultural and religious diversity.

The APAs’ have betrayed the public trust as scientific organizations committed to the broader public interest, and are in fact socio-political groups committed to reforming society in their own image.

The APAs’ have failed to disclose that there are parenting methods which help to prevent gender-identity confusion in children, and thus may also prevent future homosexuality.

IMAGINE: The APAs’ are found guilty of misleading patients and the public about a condition that is associated with maladaptive lifestyles and life-threatening disease.

IMAGINE: School superintendents testifying they encouraged young students to adopt a gay identity–simply because they were “following the professional advice” of the APAs’.

IMAGINE: A multi-million dollar settlement.

IMAGINE: Such loss prompts the APAs to launch their own internal investigation.

IMAGINE: Those internal investigations reveal confusion, intimidation, and apathy by their leadership. They are found guilty of allowing a small but powerful political-activist coalition to create a stranglehold on public-policy matters.

IMAGINE: As a result of APAs’ internal investigation, both APAs’ recommit themselves to:

Dissemination of public-health information based upon objective research. This research would be honestly and objectively reported, and based on experimental designs that have NOT been specifically created to serve a political purpose.

The significance of the research would no longer be interpreted according to one single group’s social-political reformist objectives.

By Joseph Nicolosi, Ph.D.

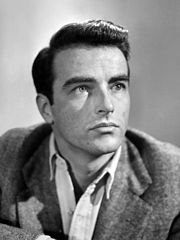

In the biography of celebrated actor Montgomery Clift, we see a striking example of some of the features found in the backgrounds of homosexual men. One background feature found rather often (though not universally) in homosexual men is the Triadic Narcissistic Family System.

Monty Clift was a broodingly handsome, classical actor who is considered to be one of the greatest screen stars of the Golden Age of film. He led a tormented life, dying prematurely after many years of drinking, drugs and a long string of affairs with men, as well as a few with women. An enormously attractive screen presence, he portrayed a haunting vulnerability and sensitivity that was evidently as much “who he was” offscreen as it was onscreen.

In Clift’s biography, we see the classic maternal (over-involved) and paternal (withdrawn) parenting style in the lives of homosexual men, with Monty as the “good” son who does not rebel — which would have been the healthier response– but instead becomes the perfectionistic high-achiever, growing up unable to trust his own feelings. He and his siblings harbor a family secret that something was very wrong behind the perfectionistic family image, but they are not sure what it is. The same-sex-attracted (SSA) son was the sensitive child, the one among the siblings who absorbed the expectations of the well-meaning but narcissistic parent; and the child whose restless drivenness and inability to trust his feelings gradually leads, in adulthood, to his self-destruction.

The Family Secret

A common feature of the Triadic Narcissistic family system is the existence of some unspoken secret that was kept from outsiders, and even from themselves. Beneath the normal, even “ideal” family image, there is “something wrong,” something too weird to discuss even among siblings. Perhaps it is the secret that his parents actually didn’t love each other, or else (as Montgomery Clift’s siblings suspected), perhaps their parents weren’t the happy people they presented themselves to be.

Adult children from narcissistic family systems who enter treatment often speak to their siblings to confirm their own perception of some kind of distortion: “Was it true,” they ask their brothers and sisters, “that it really happened that way?” When they do share their tentative impressions, they are often surprised to discover they shared the same, “strange” impressions. The family’s conflicting messages were too confusing to sort out, making it easier to retreat to the belief that “everything was OK.”

As Montgomery Clift’s brother, Brooks, said,

“Psychologically we couldn’t take the memories…so we forgot. But at the same time we were obsessed with our childhood. We’d refer to it among ourselves, but only among ourselves. Part of each of us desperately wanted to remember our past, and when we couldn’t, it was frustrating. It caused us to weep, when we were drunk enough…”

The client from the Narcissistic Family rarely recognizes the pathology in his upbringing. At the start of therapy he may report a very normal family life– despite his inability to feel and express anger, his low self-esteem, feelings of inadequacy in relationships, depression, cynical and pessimistic moods, and difficulty in making decisions. There is often no obvious parental dysfunction; the malattunement was subtle– not easily detected. Things in the family “looked normal,” yet somehow, “felt strange.”

The Allure of Theatre and Acting

The child of the Triadic-Narcissistic Family must develop a coping mechanism to survive. He does so by creating a False Self, which we see in his role of the “Good Little Boy.” This allows him to bury his “bad” self and adapt to the demands of his environment. But in doing so, he must necessarily sever his connection with his own emotional life.

In compensation, he often develops a fascination with fantasy, theatre and acting, taking on the emotional life of someone else. If he was born with the temperamental traits of creativity and sensitivity, he will find it especially easy to retreat to fantasy.

As Montgomery Clift’s brother said, when Monty played someone else, he was at last freed from his old role as the good son, and he no longer had to live up to the image his mother imagined for him. Without guilt, he could wrest himself free of the “good boy” and claim the persona of someone else.

Another place where we often find gay men seeking meaning and spiritual solace is in the reality-denying and gender-blurring archetypes of New Age philosophy.

Failure to Emotionally Connect Leads to a Sense of Existential Meaninglessness

The child of the Narcissistic Family simply does not know himself because his parents confused their own needs with his needs. The child can never fully satisfy his parents’ perceived needs, so he feels like a failure. He feels inadequate, immature, unprepared for adult responsibility, and unready to assume control over his life. He continues to look to the expectations of others. He has grown up without knowing “who ‘owns’ the ‘should,’” because he never received accurate mirroring; that is, accurate parental attunement to who he was, separate from the parent.

Because he cannot maintain genuine emotional connectedness with himself or others, he suffers from a pervasive sense that life is empty and meaninglessness. One homosexual man explained it to me his way:

“Life is just so …[searching for a word]…. petty!”

Impairment of the Child’s Gender Maturation

The boy who grows up within the Triadic-Narcissistic Family will develop trust issues which center around the gendered self — i.e., he will fear that men will “diminish” and “degrade” him, while women (like his mother) will manipulate and control him, and drain him of his masculine power.

In Montgomery Clift: A Biography, author Patricia Bosworth describes Monty’s father Bill as passive, good-natured, and very dependent on his charismatic wife, Sunny. A successful man in the business world, Bill nevertheless deferred to this strong-willed, opinionated woman at home. “My father would do anything in the world to please Mother,” Monty’s sister Ethel said (p. 23). “She made everyone—including her husband—feel that no one with any brains could possibly disagree with her and still be a person of consequence” (p. 31).

Indeed, Sunny was known as a vibrantly attractive and intelligent woman. She was “energetic, sometimes venomous, always triumphant in any situation” (p. 284).

Sunny herself had been adopted as an infant into a family that apparently abused her, and she was never able to locate her birth parents. She had been told, however, that her bloodlines made her a “thoroughbred.” She became obsessed with tracking down her genealogy, and she poured all her energy into it. Her primary goal in life, biographer Boswell says, was to raise her children as “the thoroughbreds they were” so they would never know the insecurity she had suffered in her life. She gave birth to two boys (Monty and Brooks) and one girl (Ethel). Sunny did not seem to respect their biological gender differences– “”Monty and the others were being raised as triplets, given identical haircuts…clothes, lessons, and responsibilities, regardless of age or sex.”

Brooks, the tougher son, rebelled—fighting and talking back to his mother when he was told he must dress like his younger brother and sister. “I wanted to be myself,’’ he explained later. Brooks (who grew up to be heterosexual) was married and divorced several times. However, “Monty appeared the most docile, the most obedient of the three children. He did precisely what he was told…” Biographer Bosworth notes that his “independent impulses, his drives, were curbed again and again” (p. 31) by his mother.

In spite of the intense pain the relationship brought him, Monty–his brother Brooks later recalled– “had a secretive relationship” of mutual specialness with their mother which Brooks and his sister “never intruded upon.” (p. 50). In contrast, Monty and his father “rarely communicated about anything” and in the morning, they would both read the paper while sitting at the breakfast table, “rarely exchanging a word” (p. 55) .

Isolated from his male peers, the sensitive and gentle Monty also developed an intense closeness to his sister Ethel. “Throughout his life Monty relied on Sister for comfort and advice…Their insecurities made them inseparable. By the time they were seven they were sharing every secret, every fantasy” ( p. 26).

All three children complained that they were lonely because they weren’t allowed to play with others in the neighborhood, but Sunny never explained why: she just forbade it. When Brooks later confronted his father Bill about their isolated childhood, Bill told him that he shouldn’t feel bad about it — it was for his own good–because they were special, just like their mother was:

“Everything she did for you she did because she believes you are thoroughbreds. If only I could convince you of your mother’s greatness—she is a great, great woman. She wanted you to have every advantage—and all the love she never had.” (p. 49)

“You Be Happy, So I Can Be Happy”

In the Clift family, there was apparently no room for anyone but Sunny to vent anger or express opinions. The father deferred to his wife in family disagreements, and did not defend the children. “‘Ma was always right.’ She would tell them that her entire life was dedicated to, and sacrificed for, her children, so “the least they could do” was to behave and keep her happy.

Indeed, Sunny’s happiness was understood to be essential to keeping the family together. Monty’s father, on a business trip, described himself as “miserable” whenever he was away from his wife. He wrote his son a letter, reminding him who gave the Clift family its identity:

“Your mother is the heart of the Clift family. All our hopes and ambitions center around her. We love her better than all else, and we are ambitious because of her. She is the very lifeblood of the family…” (p. 38)

Sunny tutored the children at home; her plan was that the children “would be beautifully educated but they would have to associate only with each other, ‘with their own kind.’” (p. 19)…Their father, who was often away from home, “came and went” between business deals in Manhattan and Chicago.

When the children were old enough to appreciate culture, Sunny took them to Europe for two years. Their father, says Clift’s biographer, “had worked weekends and 14-hour-long days trying to given them the creature comforts Sunny had insisted were their right, by heritage.” (p. 22) They stayed at the best hotels, but were always expected to keep to themselves.

It was not long before the Clift brothers soon began to be cruelly teased by other boys. At times, a “mob” of boys would chase them home on their bicycles.

Then, the stock market crash bankrupted the Clift family, and Bill Clift became deeply depressed. His wife, always strong through adversity, bolstered her husband and “gave me courage,” Bill said, “when nobody else would.” (p. 35) The children later recalled that both parents acted as if nothing was wrong– the children continued to “sleep on silk sheets” in the dark, dingy room they rented, and no one talked about their dire circumstances.

Hazy, Uncertain Memories

“As an adult, Monty refused to discuss his childhood with anyone—not even his closest friends” and both his brother and sister reported a similar “amnesia.” “Once they left home and began living their own lives,” Monty’s biographer said, “they blanked out much of those years” (p. 35).

Monty’s brother Brooks noted that, “Psychologically we couldn’t take the memories…so we forgot. But at the same time we were obsessed with our childhood. We’d refer to it among ourselves, but only among ourselves. Part of each of us desperately wanted to remember our past, and when we couldn’t, it was frustrating. It caused us to weep, when we were drunk enough…” (p. 36). “All three children felt profound anxieties they could not comprehend” as Sunny tried harder and harder to “cast everyone in their assigned roles, and deny their individual needs” (p. 38).

Acting as Release from a False Role

By the age of 12, Monty had found the one love of his life– becoming another person through acting. He became fascinated with the spectacle of the circus and with theatre. His brother Brooks said acting was the perfect release for Monty because when he played someone else, he was at last freed from his old role—the one created for him by his mother: “Now he [Monty] no longer had to live up to the image Sunny imagined for him,” (p. 44) Brooks said.

“You’re Special, I’m Special”

Although Sunny was fiercely devoted to her children, on a deeper level, the relationship was evidently narcissistically driven. Returning from an acting job one time, Monty teased his father, saying everyone thought Monty looked Jewish onscreen (his father disliked Jews). They began arguing. But instead of trying to make peace between them, Sunny’s question to her son was, “Monty, dear, why are you doing this to me??” (p. 285). Says his biographer:

“The sound of that question brought back memories of his boyhood when every time he attempted to be independent– to make choices, decisions — she told him he was wrong and she was right; and when he disobeyed her anyway, she would cry, “Why are you doing this to me? “ (p. 285)

Monty was 18 and working at an acting job when a fellow actor, Pat Collinge, noted that Monty’s male roommate had to move out and make bed space for Sunny to share Monty’s room whenever she visited him. “Everybody…thought it was rather odd,” Collinge said, “for an 18-year-old boy to share his bedroom with his mother” (p. 58). Collinge noted of Sunny, “I found her bewitching and charming, but a killer too. She stifled and repressed Monty by not allowing him to give vent to his enthusiasms or his deep needs” (p. 58).

At 17, Monty went away for the summer but he received a phone call from his mother every day. She discouraged him from dating and told him to conserve his energy for his career.