by Joseph Nicolosi, Ph.D.

We live in a culture where tolerance, diversity, and the right to define oneself are valued very highly. Today, people who want to live their lives as “gay” are free to do so. That’s their right.

But There’s Another Sexual Minority I’d Like To Tell You About.

These are the men and women who — despite having some homosexual feelings — believe that humanity was designed to be heterosexual.

Homosexuality will never define “who they really are.”

The major professional groups — the American Psychological Association and American Psychiatric Association — (the “APA’s”) — have abandoned these people. Today, gay activists speak for the APA’s on subjects related to homosexuality.

In contrast, “ex-gays” — the sexual minority I have been talking about — are simply forgotten.

Because they have listened only to gay activists, not ex-gays, the APA’s have promoted the myth that people are “born homosexual.” They’ve also promoted the myth that if you have homosexual attractions, that gay is simply “who you are” — and that claiming another lifestyle or identity is a betrayal of one’s “true nature.”

Also, the APA’s have abandoned the age-old understanding that children need BOTH a mother AND a father.

And they’ve promoted the myth that homosexuality is just like heterosexuality, except for the gender of the partner.

All of these ideas are … just myths.

How could this be true? I invite you to read the material posted on this web site.

In everything we write, we have worked hard to be scientifically accurate, and also to be fair and respectful in representing the ideas those who disagree with us. Because “tolerance, diversity and inclusion” are essential guidelines for both sides in any respectful debate.

That is why I am standing up for what I believe.

by Joseph Nicolosi, Ph.D.

I would like to propose a socio-analytic view of the formation of gay identity. This view is based upon the perspective I have gained from the clinical treatment of over 400 homosexually-oriented men during eighteen years as a practicing psychologist.

“The gay identity” has been portrayed as a civil-rights and self-determination issue. We Americans, who love freedom, have loved it too much and have lost our moorings. Our most influential institutions–professional psychology and psychiatry, churches, the education establishment, and the media–have fallen to the gay deception. Because gay is, I am convinced, a self-deceptive identity.

“Gay” is Not “Homosexual”

First, let’s begin with the understanding that I will not be speaking about the person who struggles with same-sex attraction, but rather the gay-identified person–which is to say, that person who is ego-invested and personally identified with the idea that homosexual behavior is as normal and natural as heterosexual behavior.

Secondly, I wish to clarify my belief that there is no such thing as a gay person. Gay is a fictitious identity seized upon by an individual to resolve painful emotional challenges. The man who recognizes that he has a homosexual problem and struggles to overcome it is not “gay.” He is, simply, “homosexual.”

To believe in the concept of a gay identity as valid, a person must necessarily deny significant aspects of human reality. The foundation typically begins with a significant denial of human reality during early childhood.

I’d like to propose a three-step, psycho-social model for the development of a gay identity–first, beginning with the prehomosexual child and his gender distortions; second, with his later assimilation into the gay counterculture, which fosters those same distortions about self and humanity; and finally, concluding by describing how the gay community’s self-deception has expanded into the further deception of a large portion of society.

Early Gender Identity

Let’s begin with the child. At a critical developmental period called the gender-identity phase, the child discovers that the world is divided between male and female. Which one is he going to be? He is personally challenged to assume maleness or femaleness — “Am I a boy? Or am I a girl?” We’ll be talking primarily about boys, because there are some more complex variations for the lesbian.

Confronted with the reality of a gendered world, male and female, and forced to make a choice, the child may first resort to an avoidance strategy–regressing into an androgynous phase: “I need not relinquish the benefits of either sex. I can be both male and female.” However, reality pushes in and language now enters, and he hears “he” and “she,” and “his” and “hers.”

Both sexes are first identified with the mother, the “first love object”–but the boy has the additional developmental task of disidentifying from the mother to move on to the father. We must make no mistake about this: masculinity, as Robert Stoller said, is an achievement. The child–especially the boy–has to work not only for the acquisition of identity, but for the acquisition of gender. Every culture that has ever survived understands this matter of the “achievement” of gender, and will support and assist the boy through rites of passage and male initiation.

Increasingly today, we are abandoning support of our boys’ formation of masculine identity; particularly the support needed from the parents. For the boy, the father is most significant in the identification process. If he is warm and receptive and inviting, the boy will disidentify with mother and bond with father to fulfill his natural masculine strings. If the father is cold, detached, harsh, or even simply disinterested, the boy may reach out, but eventually will feel hurt and discouraged and surrender his natural masculine strivings, returning to his mother.

There is no convincing scientific evidence of a “gay gene,” but certain boys do seem especially vulnerable to homosexual development. Clinical experience tells us that the boy who is sensitive, passive, gentle, and esthetically oriented may be most susceptible to retreat from the developmental challenge to gender-identify with his father. A tougher, bolder, thicker-skinned son may well succeed in pushing through an emotional barrier. The sensitive son seems to decide, “I can’t be male, but I’m not completely female either; so I will remain in my own androgynous world, my secret place of fantasy.”

And, as we shall see, this quality of androgynous fantasy endures into adulthood: in fact, it is a fundamental feature of gay culture. This fantasy contains within it, not only the narcissistic refusal to identify with a gendered culture, but also the refusal to identify with the human biological reality upon which our gendered society is based. In fact, gender–a core feature of personal identity–is central to the way we relate to ourselves and others. It is also a central pathway through which we grow to maturity.

A host of studies confirm the correlation between childhood gender nonconformity, which is suggestive of gender-identity confusion, and later homosexuality. Not all homosexuality develops this way, but this is a common developmental pathway. We hear echoes of this theme over and over in gay literature–the repeated story of the prehomosexual boy who is isolated and “on the outs” from male friends, feeling different, insecure in his masculinity and alone, disenfranchised from father, and retreating back to mother. Camille Paglia, a lesbian activist, says she struggled with a “massive gender dysfunction” throughout childhood. Andrew Sullivan, the gay author of Virtually Normal, was asked by a young classmate, “Are you a girl or a boy in there?”

Because gender was such a source of pain in childhood, the annihilation of gender differences is, not surprisingly, a central demand of gay culture. Gays often call their attitude “an indifference to gender.” Daryl Bem, a gay psychologist, describes his version of utopian society as a “non-gender-polarizing culture” in which everyone would potentially be anyone else’s lover. Other gay writers insist on an “end to the gender system.”

Detachment from Self and Others

So we see that the man who accepts the gay label in adulthood, has typically spent much of his childhood emotionally disconnected from people, particularly his male peers and his father. He also was likely to assume a false, rigid “good little boy” role within the family.

One of my clients said, “I was a non-entity. I didn’t have a place to feel.” Another man said, “I always acted out other people’s scripts for me. I was an actor in other people’s plays.”

One client said, “My parents watched me grow up”; and hearing this, another client added, “I watched myself grow up.” Do you hear that quality of detachment from self? — “I watched myself grow up.” No wonder the pre-homosexual boy is often interested in theatre and acting—” Life is theatre. We are all actors. Can’t reality just be what we wish it to be?”

In the absence of an authentic identity, it is easy to self-reinvent. Oscar Wilde (who probably was the first person to give a face to “gay”), said, “Naturalness is just another pose.”

Without domestic emotional bonds to ground him in organic identity, the gay man is plastic. He is the transformist, a Victor-Victoria, or the character from “La Cage Aux Folles.” He is pretender, jokester–what French psychoanalyst Chasseguet-Smirgel calls “the imposter.” He is what the gay, Jungian psychotherapist Robert Hopcke calls “the outsider, the trickster, the androgyne–the person who breaks the boundaries in our society.”

Freud said, “The father is the reality principle.” Father represents the transition from the blissful mother-child, symbiotic relationship into harsh reality. But the pre-homosexual boy says to himself, “If my father makes me unimportant, I make him unimportant. If he rejects me, I reject him and all that he represents.” Here we see the infantile power of “no” — “Father has nothing to teach me. His power to procreate and affect the world are nothing compared to my fantasy world. What he accomplishes, I can dream. Dream and reality are the same.”

Rather than striving to find his own masculine, procreative power…moving out into the world, trying to impact it…he chooses, instead, to stay in the dreamy, good-little-boy role. Detached, not only from father and other boys, but from maleness and his own male body–including the first symbol of masculinity, his own penis–an object alien even to himself. He will later try to find healing through another man’s penis. Because that is what homosexual behavior is: the search for the lost masculine self.

Since anatomically grounded gender is a core feature of individual identity, the homosexual has not so much a sexual problem, as an identity problem. He has a sense of not being a part of other people’s lives. Thus it follows that narcissism and preoccupation with self are commonly observed in male homosexuals.

The Identity Search is Felt as Homoeroticism

Now in his early teenage years, unconscious drives to fill this emotional vacuum–to want to connect with his maleness–are felt as homoerotic desires. The next stage will be entry into the gay world.

Then for the first time in his life, this lonely, alienated young man meets (through gay romance novels from the library, television personalities, or internet chat rooms) people who share the same feelings. But he gets more than empathy: along with the empathy comes an entire package of new ideas and concepts about sex, gender, human relationships, anatomical relationships, and personal destiny.

Next he experiences that heady, euphoric, pseudo-rite-of-passage called “coming out of the closet.” It is just one more constructed role to distract him from the deeper, more painful issue of self-identity. Gay identity is not “discovered” as if it existed a priori as a natural trait. Rather, it is a culturally approved process of self-reinvention by a group of people in order to mask their collective emotional hurts. This bogus claim to have finally found one’s authentic identity through gayness is perhaps the most dangerous of all the false roles attempted by the young person seeking identity and belonging. At this point, he has gone from compliant, “good little boy” of childhood, to sexual outlaw. One of the benefits of membership in the gay subculture is the support and reinforcement he receives for reverting to fantasy as a method of problem solving.

The Fantasy Option

He is now able to do collectively what he did alone as a child: when reality is painful, choose the fantasy option. “I have merely to redefine myself and redefine the world. If others won’t play my game, I’ll charm and manipulate them. If that doesn’t work, I’ll have a temper tantrum.”

For that lonely child, what awesome benefits of membership he receives by assuming the gay self-label! He receives unlimited sex and unlimited power by turning reality on its head. He enjoys vindication of early childhood hurts. Plus as an added bonus, he gets to reject his rejecting father and similarly, the Judeo-Christian Father-God who separated good from bad, right from wrong, truth from deception. Oscar Wilde said, “Morality is simply an attitude we adopt toward people whom we personally dislike.”

Next, we move on to look at the third level: “How has this group of hurt boys and girls–now known in adulthood as the gay community–managed to promote their make-believe liberation not only to popular culture but to legislators, public-policy makers, universities, and churches?

There are a number of ways, but three such avenues stand out for mention.

The first is the civil-rights movement, probably the single most influential force in forming the collective consciousness of American society in this century. Gay apologists have used authentic rights issues as a wedge to promote their redefinition of human sexuality and, essentially, human nature. And one powerful tool that has been used time and time again is the Coming Out Story. It is that same generic story that has been repeated almost verbatim for thirty years now–from the committee rooms of the American Psychiatric Association in 1973, to the Oprah Winfrey Show.

I have seen religious clergy warmly applauding coming-out stories. And why not? Because “finding oneself” and “being who one really is” are popular late-twentieth-century themes which have a heroic and attractive ring to them. Certainly the person telling the story is sincere. He means what he says, but the audience rarely looks beyond his words to understand his coming-out in the larger context.

A second factor is that sexuality itself is in crisis, with fundamental changes now taking place in our definition of family, community, procreation, marriage, and gender. All of these changes have occurred in the service of an individual’s right to pursue sexual pleasure. But historically, although the gay- rights movement followed along on the coattails of the civil-rights movement, it continues to draw its ideological power from the sexual-liberation movement.

There is at this time, a cultural vulnerability to gay-lib rhetoric. Chasseguet-Smirgel says the “pervert” (in the traditional psychoanalytic sense of the term) confuses two essential human realities: the distinction between the generations, and between the sexes. In gay ideology, we see just this sort of obliteration of differences.

Similarly, Midge Decter tells us we are a culture that treats our children like adults (we have only to look at sex education in elementary school), at the same time that adults are acting like children.

Ours is a consumer-oriented society, and consumer products shape our views of ourselves. Marketing strategists are all-too-ready to target consumer groups. Gay couples are called “DINKS”–dual income, no kids. And that means expendable income. Merchants have always been ready to cater to gay clientele, and merchant-solicitors have given the gay community the face of legitimacy. Today, nearly every major corporation offers services specially tailored to homosexuals–corporations like AT&T, Hyatt House, Seagrams, Apple Computer, Time-Warner, and American Express. Alcohol and cigarettes are popular gay items. We see gay resorts, gay cruises, gay theatre, gay film festivals. Gay magazines, movies and fiction give face and theme to individuals whose essential problem is identity and belonging. Luxury items–jewelry, fashions, furnishings, and cosmetics are ready to soothe, flatter, and gratify a hurting minority. But beyond material reassurance, these luxury items equate gay identity with economic success– “The gay life is the good life.”

Yet “gay” remains a counter-identity, a negative. By that I mean it gets its psychic energy by “what I am not,” and is an infantile refusal to accept reality. Through justification offered through today’s liberal-arts education, it is easily rationalized by the arguments of deconstructionism.

Deconstructionism and the gay agenda are perfectly compatible. They conform to a number of corresponding, modern movements, including the trend against “species-ism”–promoting the idea that man must lay no claim to being above animals. Animal liberationist and founder of PETA Ingrid Newkirk says that “a rat… is a pig…is a dog…is a boy.”

There are also movements to break down the barriers between the generations, evidenced by psychiatry’s recent loosening of the diagnostic definition of pedophilia, and the publishing of the double Journal of Homosexuality issue, “Male Intergenerational Love” (an apologia for pedophilia). There are popular movements (primarily gay and feminist) to deny any mental and emotional differences between the sexes, and–even more alarmingly–nature-worship movements which resymbolize the instincts as sacred.

The founder of the deconstructionist movement is Michel Foucault, a gay man whose philosophical views emerged out of his own personal struggle with homosexuality. Foucault actally had the outrageous plan to deconstruct the distinction between life and death; in his later years, he was obsessed with the idea of simultaneously experiencing death and orgasm. He eventually succeeded, as Charles Socarides says, in “deconstructing himself” (he died of AIDS in a sanitarium).

And so through deconstructionism we see animal confused with human, sacred confused with profane, adult confused with child, male confused with female, and life confused with death — all of these, traditionally the most profound of distinctions and separations, are now under siege through modern deconstructionism.

“Gay” in Film Mythology

In the recent animated Disney film, the Lion King, we see the age-old generational link in the proud and loving relationship between the father Mufasa, king of the lions, and his little son Simba, the future king. They live in the balanced, ordered world of the lion kingdom. Now we also have this other character Scar, the brooding, resentful brother of the king, who lives his life on the outside and is full of envy and anger. It has been argued that Scar is a gay figure.

In the film, it is Scar who ruptures the father-son link between the generations. He kills the Lion King while aligning himself with a scavenger pack of hyenas. Thus Scar turns the ordered lion kingdom into chaos and ruin. But before all this occurs, we hear a brief, light-hearted dialogue between the young male cub, Simba, and his uncle Scar.

Laughingly Simba says, “Uncle Scar, you’re weird.”

Meanfully, Scar replies, “You have no idea.”

The Way Out

And so we have seen that gay is a compromise identity seized upon by an individual, and increasingly supported by our society, in order to resolve emotional conflicts. It is a collective illusion; truly, “the gay deception.” But I have seen more men than I can count in the process of struggle, growth and change. The struggle is a soul-searing one, challenging, as it must, a false identity rooted in one’s earliest years.

As adults, these strugglers have looked into the gay lifestyle and returned disillusioned by what they saw. Rather than wage war against the natural order of society, they have chosen to take up the challenge of an interior struggle. This is, I am convinced, the only true solution to an age-old identity problem.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Chasseguet-Smirgel, Jeannine (1984). Creativity and Perversion. New York, New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Disney Press (1994). The Lion King. New York, New York.

Miller, James E. (1993). The Passion of Michel Foucault. New York, New York: Simon & Schuster.

by Joseph Nicolosi, Ph.D.

IMAGINE: A class-action suit against the American Psychiatric and Psychological Associations–initiated by homosexual strugglers and their families because of the A.P.A.s’ failure to disclose that homosexuality is a treatable condition.

IMAGINE: Men and women testifying that:

Based upon the APAs’ policy recommendations, mental-health counselors had neglected to tell them about all available treatment options.

At a very vulnerable time in their lives, they were advised–without any conclusive scientific evidence–that they were “born gay,” or “had a gay gene.”

They were told to surrender their hope of ever living a traditional family life of spouse and children, and “work through their internalized homophobia” so they could learn to enjoy something they believed was incompatible with their core being.

They were not properly informed that acceptance of a gay identity would lead to greater risk for anxiety, depression, low self-esteem, loneliness, suicide attempts, failed relationships, drug use, alcohol abuse, tobacco use, and addiction to unhealthy (exotic) sexual practices, as well as STD’S and AIDS.

IMAGINE: Attorneys for the plaintiffs showing:

In many cases, gay-affirmative therapy (the psychotherapist’s advice to accept a gay identity) is not appropriate for the patient, and is induced through coercion.

Public-policy statements by the APAs’ regarding the “normalcy” of homosexuality are not and cannot be scientifically neutral conclusions, but are influenced by the social-political philosophy of the time.

Interpretation of the scientific data has been skewed to support the APAs’ favored social philosophy.

The APAs’ systemical withholding of relevant information has restricted the patient’s right to choose from among all reasonable treatment options.

The APAs’ have shown callous disregard for cultural and religious diversity.

The APAs’ have betrayed the public trust as scientific organizations committed to the broader public interest, and are in fact socio-political groups committed to reforming society in their own image.

The APAs’ have failed to disclose that there are parenting methods which help to prevent gender-identity confusion in children, and thus may also prevent future homosexuality.

IMAGINE: The APAs’ are found guilty of misleading patients and the public about a condition that is associated with maladaptive lifestyles and life-threatening disease.

IMAGINE: School superintendents testifying they encouraged young students to adopt a gay identity–simply because they were “following the professional advice” of the APAs’.

IMAGINE: A multi-million dollar settlement.

IMAGINE: Such loss prompts the APAs to launch their own internal investigation.

IMAGINE: Those internal investigations reveal confusion, intimidation, and apathy by their leadership. They are found guilty of allowing a small but powerful political-activist coalition to create a stranglehold on public-policy matters.

IMAGINE: As a result of APAs’ internal investigation, both APAs’ recommit themselves to:

Dissemination of public-health information based upon objective research. This research would be honestly and objectively reported, and based on experimental designs that have NOT been specifically created to serve a political purpose.

The significance of the research would no longer be interpreted according to one single group’s social-political reformist objectives.

By Joseph Nicolosi, Ph.D.

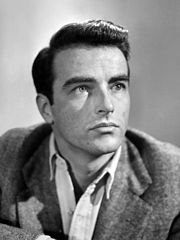

In the biography of celebrated actor Montgomery Clift, we see a striking example of some of the features found in the backgrounds of homosexual men. One background feature found rather often (though not universally) in homosexual men is the Triadic Narcissistic Family System.

Monty Clift was a broodingly handsome, classical actor who is considered to be one of the greatest screen stars of the Golden Age of film. He led a tormented life, dying prematurely after many years of drinking, drugs and a long string of affairs with men, as well as a few with women. An enormously attractive screen presence, he portrayed a haunting vulnerability and sensitivity that was evidently as much “who he was” offscreen as it was onscreen.

In Clift’s biography, we see the classic maternal (over-involved) and paternal (withdrawn) parenting style in the lives of homosexual men, with Monty as the “good” son who does not rebel — which would have been the healthier response– but instead becomes the perfectionistic high-achiever, growing up unable to trust his own feelings. He and his siblings harbor a family secret that something was very wrong behind the perfectionistic family image, but they are not sure what it is. The same-sex-attracted (SSA) son was the sensitive child, the one among the siblings who absorbed the expectations of the well-meaning but narcissistic parent; and the child whose restless drivenness and inability to trust his feelings gradually leads, in adulthood, to his self-destruction.

The Family Secret

A common feature of the Triadic Narcissistic family system is the existence of some unspoken secret that was kept from outsiders, and even from themselves. Beneath the normal, even “ideal” family image, there is “something wrong,” something too weird to discuss even among siblings. Perhaps it is the secret that his parents actually didn’t love each other, or else (as Montgomery Clift’s siblings suspected), perhaps their parents weren’t the happy people they presented themselves to be.

Adult children from narcissistic family systems who enter treatment often speak to their siblings to confirm their own perception of some kind of distortion: “Was it true,” they ask their brothers and sisters, “that it really happened that way?” When they do share their tentative impressions, they are often surprised to discover they shared the same, “strange” impressions. The family’s conflicting messages were too confusing to sort out, making it easier to retreat to the belief that “everything was OK.”

As Montgomery Clift’s brother, Brooks, said,

“Psychologically we couldn’t take the memories…so we forgot. But at the same time we were obsessed with our childhood. We’d refer to it among ourselves, but only among ourselves. Part of each of us desperately wanted to remember our past, and when we couldn’t, it was frustrating. It caused us to weep, when we were drunk enough…”

The client from the Narcissistic Family rarely recognizes the pathology in his upbringing. At the start of therapy he may report a very normal family life– despite his inability to feel and express anger, his low self-esteem, feelings of inadequacy in relationships, depression, cynical and pessimistic moods, and difficulty in making decisions. There is often no obvious parental dysfunction; the malattunement was subtle– not easily detected. Things in the family “looked normal,” yet somehow, “felt strange.”

The Allure of Theatre and Acting

The child of the Triadic-Narcissistic Family must develop a coping mechanism to survive. He does so by creating a False Self, which we see in his role of the “Good Little Boy.” This allows him to bury his “bad” self and adapt to the demands of his environment. But in doing so, he must necessarily sever his connection with his own emotional life.

In compensation, he often develops a fascination with fantasy, theatre and acting, taking on the emotional life of someone else. If he was born with the temperamental traits of creativity and sensitivity, he will find it especially easy to retreat to fantasy.

As Montgomery Clift’s brother said, when Monty played someone else, he was at last freed from his old role as the good son, and he no longer had to live up to the image his mother imagined for him. Without guilt, he could wrest himself free of the “good boy” and claim the persona of someone else.

Another place where we often find gay men seeking meaning and spiritual solace is in the reality-denying and gender-blurring archetypes of New Age philosophy.

Failure to Emotionally Connect Leads to a Sense of Existential Meaninglessness

The child of the Narcissistic Family simply does not know himself because his parents confused their own needs with his needs. The child can never fully satisfy his parents’ perceived needs, so he feels like a failure. He feels inadequate, immature, unprepared for adult responsibility, and unready to assume control over his life. He continues to look to the expectations of others. He has grown up without knowing “who ‘owns’ the ‘should,’” because he never received accurate mirroring; that is, accurate parental attunement to who he was, separate from the parent.

Because he cannot maintain genuine emotional connectedness with himself or others, he suffers from a pervasive sense that life is empty and meaninglessness. One homosexual man explained it to me his way:

“Life is just so …[searching for a word]…. petty!”

Impairment of the Child’s Gender Maturation

The boy who grows up within the Triadic-Narcissistic Family will develop trust issues which center around the gendered self — i.e., he will fear that men will “diminish” and “degrade” him, while women (like his mother) will manipulate and control him, and drain him of his masculine power.

In Montgomery Clift: A Biography, author Patricia Bosworth describes Monty’s father Bill as passive, good-natured, and very dependent on his charismatic wife, Sunny. A successful man in the business world, Bill nevertheless deferred to this strong-willed, opinionated woman at home. “My father would do anything in the world to please Mother,” Monty’s sister Ethel said (p. 23). “She made everyone—including her husband—feel that no one with any brains could possibly disagree with her and still be a person of consequence” (p. 31).

Indeed, Sunny was known as a vibrantly attractive and intelligent woman. She was “energetic, sometimes venomous, always triumphant in any situation” (p. 284).

Sunny herself had been adopted as an infant into a family that apparently abused her, and she was never able to locate her birth parents. She had been told, however, that her bloodlines made her a “thoroughbred.” She became obsessed with tracking down her genealogy, and she poured all her energy into it. Her primary goal in life, biographer Boswell says, was to raise her children as “the thoroughbreds they were” so they would never know the insecurity she had suffered in her life. She gave birth to two boys (Monty and Brooks) and one girl (Ethel). Sunny did not seem to respect their biological gender differences– “”Monty and the others were being raised as triplets, given identical haircuts…clothes, lessons, and responsibilities, regardless of age or sex.”

Brooks, the tougher son, rebelled—fighting and talking back to his mother when he was told he must dress like his younger brother and sister. “I wanted to be myself,’’ he explained later. Brooks (who grew up to be heterosexual) was married and divorced several times. However, “Monty appeared the most docile, the most obedient of the three children. He did precisely what he was told…” Biographer Bosworth notes that his “independent impulses, his drives, were curbed again and again” (p. 31) by his mother.

In spite of the intense pain the relationship brought him, Monty–his brother Brooks later recalled– “had a secretive relationship” of mutual specialness with their mother which Brooks and his sister “never intruded upon.” (p. 50). In contrast, Monty and his father “rarely communicated about anything” and in the morning, they would both read the paper while sitting at the breakfast table, “rarely exchanging a word” (p. 55) .

Isolated from his male peers, the sensitive and gentle Monty also developed an intense closeness to his sister Ethel. “Throughout his life Monty relied on Sister for comfort and advice…Their insecurities made them inseparable. By the time they were seven they were sharing every secret, every fantasy” ( p. 26).

All three children complained that they were lonely because they weren’t allowed to play with others in the neighborhood, but Sunny never explained why: she just forbade it. When Brooks later confronted his father Bill about their isolated childhood, Bill told him that he shouldn’t feel bad about it — it was for his own good–because they were special, just like their mother was:

“Everything she did for you she did because she believes you are thoroughbreds. If only I could convince you of your mother’s greatness—she is a great, great woman. She wanted you to have every advantage—and all the love she never had.” (p. 49)

“You Be Happy, So I Can Be Happy”

In the Clift family, there was apparently no room for anyone but Sunny to vent anger or express opinions. The father deferred to his wife in family disagreements, and did not defend the children. “‘Ma was always right.’ She would tell them that her entire life was dedicated to, and sacrificed for, her children, so “the least they could do” was to behave and keep her happy.

Indeed, Sunny’s happiness was understood to be essential to keeping the family together. Monty’s father, on a business trip, described himself as “miserable” whenever he was away from his wife. He wrote his son a letter, reminding him who gave the Clift family its identity:

“Your mother is the heart of the Clift family. All our hopes and ambitions center around her. We love her better than all else, and we are ambitious because of her. She is the very lifeblood of the family…” (p. 38)

Sunny tutored the children at home; her plan was that the children “would be beautifully educated but they would have to associate only with each other, ‘with their own kind.’” (p. 19)…Their father, who was often away from home, “came and went” between business deals in Manhattan and Chicago.

When the children were old enough to appreciate culture, Sunny took them to Europe for two years. Their father, says Clift’s biographer, “had worked weekends and 14-hour-long days trying to given them the creature comforts Sunny had insisted were their right, by heritage.” (p. 22) They stayed at the best hotels, but were always expected to keep to themselves.

It was not long before the Clift brothers soon began to be cruelly teased by other boys. At times, a “mob” of boys would chase them home on their bicycles.

Then, the stock market crash bankrupted the Clift family, and Bill Clift became deeply depressed. His wife, always strong through adversity, bolstered her husband and “gave me courage,” Bill said, “when nobody else would.” (p. 35) The children later recalled that both parents acted as if nothing was wrong– the children continued to “sleep on silk sheets” in the dark, dingy room they rented, and no one talked about their dire circumstances.

Hazy, Uncertain Memories

“As an adult, Monty refused to discuss his childhood with anyone—not even his closest friends” and both his brother and sister reported a similar “amnesia.” “Once they left home and began living their own lives,” Monty’s biographer said, “they blanked out much of those years” (p. 35).

Monty’s brother Brooks noted that, “Psychologically we couldn’t take the memories…so we forgot. But at the same time we were obsessed with our childhood. We’d refer to it among ourselves, but only among ourselves. Part of each of us desperately wanted to remember our past, and when we couldn’t, it was frustrating. It caused us to weep, when we were drunk enough…” (p. 36). “All three children felt profound anxieties they could not comprehend” as Sunny tried harder and harder to “cast everyone in their assigned roles, and deny their individual needs” (p. 38).

Acting as Release from a False Role

By the age of 12, Monty had found the one love of his life– becoming another person through acting. He became fascinated with the spectacle of the circus and with theatre. His brother Brooks said acting was the perfect release for Monty because when he played someone else, he was at last freed from his old role—the one created for him by his mother: “Now he [Monty] no longer had to live up to the image Sunny imagined for him,” (p. 44) Brooks said.

“You’re Special, I’m Special”

Although Sunny was fiercely devoted to her children, on a deeper level, the relationship was evidently narcissistically driven. Returning from an acting job one time, Monty teased his father, saying everyone thought Monty looked Jewish onscreen (his father disliked Jews). They began arguing. But instead of trying to make peace between them, Sunny’s question to her son was, “Monty, dear, why are you doing this to me??” (p. 285). Says his biographer:

“The sound of that question brought back memories of his boyhood when every time he attempted to be independent– to make choices, decisions — she told him he was wrong and she was right; and when he disobeyed her anyway, she would cry, “Why are you doing this to me? “ (p. 285)

Monty was 18 and working at an acting job when a fellow actor, Pat Collinge, noted that Monty’s male roommate had to move out and make bed space for Sunny to share Monty’s room whenever she visited him. “Everybody…thought it was rather odd,” Collinge said, “for an 18-year-old boy to share his bedroom with his mother” (p. 58). Collinge noted of Sunny, “I found her bewitching and charming, but a killer too. She stifled and repressed Monty by not allowing him to give vent to his enthusiasms or his deep needs” (p. 58).

At 17, Monty went away for the summer but he received a phone call from his mother every day. She discouraged him from dating and told him to conserve his energy for his career.

It was not long before Monty began dating men. One of them described Monty as a “beautiful darling boy” who was “incapable of growing up” (p. 66). Monty slowly began to make a life apart from his mother. However, his closest lifelong friends (most notably, Elizabeth Taylor) were, like his mother, magnetic, strong-willed women with whom he became enmeshed in intense (platonic) relationships. “As time passed, Monty slept with both men and women indiscriminately in an effort to discover his sexual preference, but his conflict remained obvious” (p. 67) says his biographer.

The rest of Montgomery Clift’s life was marred by alcoholism and depression. The hostile-dependent relationships he developed with platonic women friends caused him recurrent distress: “Some days he would threaten to stop seeing Elizabeth Taylor – then, the thought would make him burst into tears.” (p. 369) No doubt Clift enjoyed the sense of mutual specialness such relationships created, in a reenactment of the sense of specialness he had shared in the hostile-dependent bond he had had with his mother.

Later in life, he had a near-fatal car accident when he was driving home drunk from a party, which left him with permanent facial disfigurement, and started him down a yet deeper spiral of depression.

The death of this brilliant and magnetic actor – in a tragic end, alone at age 45 in a hotel room — was said to be brought on by complications from his longtime drug use and alcoholism. Yet there is no doubt that this sensitive child of a narcissistic family system, growing up with the resulting ill-effects on sexual orientation and personal individuation, had been simply unable to cope with the demands of life.

by Joseph Nicolosi, Ph.D.

On January 13th, 2015, I was a guest on the “Dr. Phil Show” when a segment was aired on children who want to be the opposite sex.

Also appearing on the show was the mother of a transgendered boy who is living life as a girl, and several psychotherapists who believe that transgenderism is normal, natural and healthy for some people.

I took the position that children should not, however, be encouraged to think of themselves–and live as–as the opposite sex. All of the other psychotherapists disagreed with me.

“Imitative Attachment” in the Gender-Disturbed Boy

“Gender-identity disorder is primarily an attachment problem.” These words, spoken by me during the TV interview, were edited out, but they are critical to the understanding of gender-disturbed children. No one on the show discussed this issue.

GID children do not necessarily suffer from a lack of parental love. But to begin to understand the GID child, we must understand that in early infancy, the child’s sense of self is very fragile, and is formed in relationship to the mother. The mother is the source and symbol of the child’s very existence. It is a simple, biological reality that infants cannot survive without a nurturing caregiver.

Experts in the area of childhood gender-identity disorder (GID) have found certain patterns in the backgrounds of GID children. A common scenario is an over-involved mother with an intense, yet insecure attachment between mother and child. Mothers of GID children usually report high levels of stress during the child’s earliest years.

We often see severe maternal clinical depression during the critical attachment period (birth to age 3) when the child is individuating as a separate person, and when his gender identity is being formed. The mother’s behavior was often highly volatile during this time, which could have been due to a life crisis (such as a marital disruption), or from a deeper psychological problem in the mother herself -i.e., borderline personality disorder, narcissism, or a hysterical personality type.

When the mother is alternately deeply involved in the boy’s life, and then unexpectedly disengaged, the infant child experiences an attachment loss–what we call “abandonment-annihilation trauma.” Some children’s response is an “imitative identification”– the unconscious idea that “If I become Mommy (i.e., become female), then I take Mommy into me and I will never lose her.”

This is the same dynamic that we see in the fetish, where the boy is “taking in a piece of Mommy” (her shoes, her scarf) and developing an intense (and later sexualized) attachment to an object associated with her.

The infantile dynamic of “imitative attachment” is such that “keeping Mommy inside” becomes truly a life-or-death issue – “Either I become Mommy, or I cease to exist.” This explains why gender-disturbed boys are willing to tolerate social rejection for their opposite-sex role-playing–it feels like death to abandon this perception of themselves as a female.

The phenomenon of “imitative attachment” explains why gender-disturbed boys do not display femininity in a natural, biologically based way, as do girls; but rather, demonstrate a one-dimensional caricature of femininity–exaggerated interest in girls’ clothes, makeup, purse-collecting, etc. and a mimicry of a feminine manner of speaking.

As one mother explained to me, “My GID boy is more ‘feminine’ than his sisters.”

“Born that Way?”

Although I believe gender disturbances always involve some kind of attachment problem, there may also be biological influences that lead some children in that direction.

One psychiatrist on the show discussed a recent, credible biological theory. For at least some boys who want to be girls, there may have been an unusual biological developmental problem, during the time when the then-unborn child was being formed in the uterus. This resulted in the incomplete masculinization of the boy’s brains. These boys’ brains are more feminine than other boys’; in extreme cases, they may grow up feeling like girls trapped in a male body.

This biological theory has some credible support–in fact, it may well explain some cases of gender disturbance. But science has, as yet, no biological test that can confirm that this brain event has actually occurred. Furthermore, we know that human emotional attachment changes the structure of the infant’s brain after birth. So if we encourage the gender-disturbed boy to act like a girl, we will never know to what extent he could have become more comfortable with his biological sex if his parents were committed to actively reinforcing his normal, biologically appropriate gender identity and working to address the psychological problem of imitative attachment with the mother.

In our clinical work with GID boys, we see genuine, positive changes occur. We never shame the child for acting like a girl; we reinforce him for biologically appropriate behaviors and encourage him to grow more comfortable as a boy, thus helping him to sense that being a boy (and internalizing a masculine identity) is safe, and that being a boy is good.

No one on the Dr. Phil Show mentioned the implications of taking the opposite approach–actively preparing a boy for future sex-change surgery. Surgery can never truly change a person’s sex. Doctors can remove the male genitals and form an imitation of the sex female sex organs, but they cannot make the simulated organs reproductively functional. The DNA in a boy’s body cells cannot be changed with surgery. Thus, after sex reassignment surgery, there will still be a typically male genotype present.

We believe that every effort should be made to help a gender-disturbed boy accept his biological maleness, and be comfortable in life with the intact (not surgically mutilated) body with which he was born.

by Joseph Nicolosi, Ph.D.

The easy availability of pornography and consequent addiction to it, has reached epidemic proportions that the media continues to ignore. For the man with SSA, gay porn becomes a particular problem because of the natural but frustrated desires it represents.

As I work with SSA men, it becomes apparent to many of them that its appeal lies in porn’s seeming fulfillment of three emotional drives: (1) Body Envy, (2) Assertive Attitude and (3) Need for Vulnerable Sharing.

If, upon reflection, the client agrees that his attraction to porn is rooted in the above motivations, then we proceed to work on them. If not, then we approach the issue from another direction.

Let us review each of these emotional needs described above, and see how they can be represented in gay porn.

Body Envy

Usually the first identified need is the desire for a body like the personified image. The porn actor possesses qualities of masculinity regarding which the client usually feels inadequate. For each client, those masculine features may differ, but the common elements are muscularity, body hair, large build, and the archetypal image of masculinity, a large penis, which the client often feels are shamefully lacking within himself.

Assertive Attitude

In addition to body image, the client is drawn to a display of directness, non-inhibition and bold aggression. These are exactly what most clients lack in their own life, especially, due to their inhibited and sexualized relationships with other men.

Vulnerable Sharing

With further exploration, the client may identify his attraction to porn, to the idea that it offers open sharing with another man. Sexual activity between two men offers a fantasy image of vulnerable sharing and the illusion of a deep level of mutual acceptance and validation which are painfully absent in his male relationships.

Fantasy for Reality

Diminished interest in gay porn occurs as the client begins to understand that he is pursuing normal, healthy and valid needs through this fantasy and wishful thinking. Yetwhile apparently emotionally “safe,” gay porn offers nothing but temporary relief from loneliness and alienation from other men. The client is encouraged by his therapist to surrender this false intimacy for authentic friendship. While it offers him momentary “safety” from the anticipation of shame-invoking rejection by other men, porn satisfies only in the moment.

The three therapeutic techniques for uncovering the client’s unconscious needs are: (1) Inquiry-Investigation, (2) Body Work, and (3) EMDR. The effectiveness of each technique depends upon the client. The therapist may combine them, but as a general rule, Body Work is more effective than Inquiry-Investigation, and EMDR is more effective than Body Work. (Body Work involves the development of self-attunement and does not involve touching.)

The client’s recognition of porn as merely fantasy projection of unmet needs inevitably leads the motivated client to ask: “Well, then how do I get these needs met?” His question marks the second phase of Reparative Therapy and the process out of gay porn, and more importantly, out of homosexuality itself. Preoccupation with male porn always represents the client’s own sense of masculine inferiority made manifest in these three aspects, and investigation into the life of the SSA client always reveals a lack of authentic male friendships.

Memories of boyhood shaming by dominant males often surface during therapeutic exploration. Porn actors, after all, represent the kind of men who intimidate our client. The client comes to realize that through porn, he can dominate or be dominated by the men who once frightened him. Through porn, he can engage in imaginary play and feel a pseudo-acceptance from the kinds of men who have humiliated and rejected him.

As the client comes to identify how he projects onto the porn image his unmet needs and as he fulfills those needs in real male friendships, the compelling power of the porn image diminishes. Clinical reports tell us that the client may eventually find such images not only uninteresting and non-arousing, but repellant in the same way that such images are experienced by heterosexual men.

by Joseph Nicolosi, Ph.D.

Reparative Therapy® posits two fundamentally distinct self-states: The Assertive Self- State within which the client finds his true self, and the Shame Self-State within which he experiences his false self. In working on overcoming his gay porn addiction, the client comes to realize that in order to become sexually aroused, he must first leave his Assertive True Self and shift into a Shamed False Self. He does this without his awareness, but the eventual realization serves to expose the fantasy nature of the attraction, diminishing the grip of his addiction, as well as his homosexuality.

The Self-State distinction essential to Reparative theory finds theoretical support in the writings of Joyce McDougall. In her clinical studies, she confirms our understanding of homosexual enactment as a gender-based self-reparation.

Among the few contemporary psychoanalysts willing to study what were once called the perversions, Joyce McDougall has investigated the central role of theatre and role-playing in perverse forms of sexual activity, including homosexuality.

McDougall understands “sexual theatre” to be essential to perverse sexual behavior which is rooted in a symbolic attempt to resolve a personal identity conflict. In this regard she confirms the classic psychoanalytic understanding of perverse sexual activity as being rooted in identity confusion. Noting the repetitive-compulsive nature of these role enactments, McDougall found that while her patients complain about the constrained structure of these “erotic theatre pieces,” they could not abstain from their enactments: “…and have to do it again and again and again” (McDougall, 2000, p.182).

The compulsive/repetitive enactment of these rituals represents a symbolic attempt to resolve psychic conflict caused by a problematic parental message regarding the child’s sexuality. In the extreme case of transsexuals, for example, McDougall reports that her patients…“felt that at last they would be recognized by the mother and what she had always unconsciously desired for them” (McDougall, 2000, p.186). These “erotic scenarios” serve to safeguard the feeling of sexual identity but are a technique of psychic survival in that they preserve the feeling of subjective identity. As “compulsive neo-sexual inventions,” they represent the best possible solution that the child of the past was able to find in the face of contradictory parental communications regarding gender identity and sex role. “And they come to the child or the adolescent as revelation of what his or her sexuality is, along with the sometimes painful recognition that it is somehow different from that of others: there is no awareness of choice” (McDougall, 1986, p.21). Further, she saw these dramatic and compulsive enactments as ways of preserving the narcissistic self-image from disintegration: “Thus the act becomes a drug intended to disperse feelings of violence, as well as a threatened loss of ego boundaries, and a feeling of inner death. Meanwhile the partner and the sexual scenario become containers for dangerous parts of the individual. These will subsequently be mastered, in illusory fashion, by gaining erotic control over the other or through a game of mastery within the sexual scenario” (McDougall, 1986, p. 21).

Bibliography

McDougall, Joyce, Arnold Modell, and Phyllis Meadow (2000) “Sexuality Reconsidered: A Panel Discussion.” Modern Psychoanalysis, 25:181-189.

McDougall, Joyce, (1986) “Identifications, Neo-needs and Neo-sexualities,” International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 67:19-30.

Nicolosi, Joseph (2009), Shame and Attachment Loss: The Practical Work of Reparative Therapy. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press.

by Joseph Nicolosi, Ph.D. and Linda A. Nicolosi

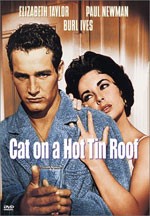

“Cat on a Hot Tin Roof” was a Broadway play, later made into a compelling movie starring Elizabeth Taylor and Paul Newman.

The play is heavily biographical for its author, Tennessee Williams. Shy, sensitive and frail as a child due to a debilitating bout with diptheria, Williams believed that he was a disappointment to his father, a man known for alcoholism and a violent temper. Williams’ mother was a Southern Belle who was known as a strong-willed social climber; she focused her high expectations on her son when her marriage went sour. Thus the playwright’s parents seem to have created the environment of what we know as the Classic Triadic Family System, a common background in the life of homosexual men.

Tennessee WilliamsWhen in college, Williams briefly flirted with heterosexuality, as he had a crush on a female classmate. Eventually, though, he was drawn into homosexual relationships. Williams never could seem to be acceptable to his fraternity brothers, who considered him shy and awkward. He became an alcoholic and drug addict, and eventually he died of an overdose, but not before a remarkable artistic career during which he produced some of the greatest plays of the twentieth century, many of which were known to be autobiographical.

——————

The plot of “Cat” centers on “Big Daddy”’s birthday party. An aging, wealthy Southern Estate owner, “Big Daddy” is a gruff, commanding patriarch who uses material rewards as substitute for love. “What makes Big Daddy so big? …His big heart, his big belly …” his family chants, “…his big money!”

This is a play about how Big Daddy and his two sons are each deficient in the three life-forces that create masculinity: the Reality Principle, procreation, and the ability to love another person. In fact, the challenge to confront reality–resisting the temptation to substitute a narcissistic universe of make-believe– is a repeated theme in the plays of Tennessee Williams. In “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof” (said to be his favorite creative work), he seems to have been trying to work out his own struggle with reality, and with his sexuality as well.

When the story begins, Brick, the youngest son (played in the film by Paul Newman) lacks all the necessary elements of masculinity. He is neither realistic, procreative, nor loving. He is the boy stuck in a youthful narcissistic world, a rebel against the universal law, substituting fantasy and thus preserving his narcissistic illusions. His wife Maggie (Elizabeth Taylor) calls him “Boy” or “boy of mine.” He is not yet a man. He dreams of his lost past as a youthful athlete, and of a man (“Skipper”) he had a romantic fascination with. Now, he can no longer be intimate with his wife. He is constantly drunk.

Yet his name is suggestive of a solid building material for the family empire, should he ever break free of his anger and illusions.

Trying to re-live his glorious football past, Brick injures his ankle the night before Big Daddy’s birthday party while at the high-school track field (drunk) trying to jump the hurdles. Throughout the play, he is on crutches. Asked “What were you jumping high hurdles for? Brick answers, “Because I used to, and people like to do what they used to do after they’ve stopped being able to do it.”

Brick’s father, Big Daddy, represents two of the three masculine principles: the reality principle and procreation. He lives out a harsh reality (ruthless money-making) and is committed to family and to promoting his lineage. When he was young and single, he found out that Big Mama was carrying his child. He said to her, without love or tenderness: “That’s my kid, ain’t it? I want that kid. I need him. He ain’t going to have nobody else’s name but mine. Let’s get the preacher. That’s what marriage is for. Family.”

Burl Ives as Big Daddy (left) and Paul Newman as BrickBut Big Daddy’s flaw is that he does not like people. In his ruthless money-making, he has forgotten how to love. Because he is disconnected from this primary masculine principle, his wife, Big Mama, is also love-deprived and ungrounded in reality. “Truth!” Big Mama says. “Everybody keeps hollering about the truth. The truth is as dirty as lies!”

Big Mama’s relationship to Brick is possessive and intrusive, excluding her other son, Gooper. Soon after the story begins, she hears the bad news that Big Daddy has terminal cancer, and she cries out: “I want Brick. Where’s my Brick? Where’s my only son?”

Gooper represents the opposite of rebellious Brick. Gooper is the “good” sort of son who follows orders and does all the right things expected of him, keeping his wife continually pregnant with a brood of smiley-faced but malevolent children, even while Gooper and his wife secretly plot to take over the family inheritance. But he is a hollow male; materialistic and legalistic. Like Big Daddy, Gooper lives a sham reality, and like Big Daddy, he cannot love. He can procreate, but he cannot give life. His procreative power is soulless, creating not children, but unloved wild sub-creatures who have been given dogs’ names. Like animals, his children represent “a flesh-and-blood dynasty…waiting to take over”; Brick’s wife Maggie calls them “no-neck monsters” because “their fat little heads sit on their fat bodies without a bit of connection.”

Gooper’s wife, like her husband, is also soulless and money-focused. Along with Gooper, she portrays a picture-perfect family image. She uses her children to help her win the inheritance with an annoying parade of theatricalities designed to “entertain” Big Daddy and make him feel good about himself.

Married to a man who is incomplete, Gooper’s wife is unable to fulfill her feminine nature. She can procreate but cannot give birth to genuine human life. She is the Negative Feminine. Maggie, Brick’s wife, calls her “that fertility monster.”

Maggie is the only sympathetic and noble person in this dysfunctional family. Brick’s withholding of love and unrelenting cruelty toward her –while he remains obsessed with a man from the past, Skipper– has forced her to undergo, in her own words, “this horrible transformation” into becoming “hard and frantic and cruel.”

The plot repeatedly returns to the Brick’s relationship with the mysterious and unseen Skipper. This is the man who is the unspoken source of his and Maggie’s marital conflict. The relationship with Skipper was intense and mutually dependent with the suggestion of being homoerotic. Despite the devastating effect of this situation on Maggie, Brick refuses to talk about it.

Seeking the male connection he did not get from his father, Brick made Skipper the special person in his life, overshadowing and competing withhis wife. Without a man’s masculine blessing he cannot become a procreative man, cannot live in truth, and cannot love a woman. Brick wants to take masculine love from Skipper, but Skipper needs it as well, and Skipper’s suicidal end is the final result. And so Brick broods, and numbs his misery in alcohol.

A turning point in the play occurs whenBig Daddy wants to have a “private conversation” with Brick.

In his crude style he asks what is troubling his son. Revealing some glimmers of true love, Big Daddy says, “Boy, sometimes you worry me. Why do you drink?” Brick refuses to answer. All he can say is, “It’s too painful and it’s no use. We talk in circles. We have nothing to say to each other!”

Big Daddywants to know the truth about his son’s special relationship with Skipper, which he sarcastically refers to as “this great and true friendship.” Whatever happened that night when Skipper killed himself, Skipper had been devastated and screamed for help, but Brick could not save him. Brick explains this with a rhetorical question: “How does one drowning man help another drowning man?”

Big Daddy persists; asking again, “Why do you drink?”

In reply, Brick cries out; “Mendacity! It’s lies and liars! Not one lie or one person. The whole thing.” In deeper honesty, Brick adds, “That disgust with mendacity is really disgust with myself. That’s why I’m a drunk. When I’m drunk I can stand myself.”

Big Daddy agrees about the pretense that characterizes the family; but here, he reveals his fundamental difference on the principle of reality. Unlike Brick who lived with the family’s mendacity and turned it into self-hate, Big Daddy takes on gritty reality and just sees lies and falsity as an unchangeable fact of life. He answers Brick: “Look at the lies I’ve got to put up with. Pretenses, hypocrisy! Pretending like I care for Big Mama. I haven’t tolerated her in years. Church! It bores me, but I go. All those swindling lodges, social clubs, and money-grabbing auxiliaries that’s got me on their number-one sucker list. Boy, I’ve lived with mendacity. Why can’t you live with it?”

Illustrating their differing attitude on life, Brick (who dulls his own pain with alcohol) offers Big Daddy some morphine to kill the pain of his own cancer, but Big Daddy refuses: “It will kill the pain, but kill the senses, too. When you’ve got pain, at least you know you’re alive. I’m not going to stupefy myself with that stuff. I want to think clear. I want to see everything and feel everything.”

The breakthrough occurs when father and son are standing in the basement of the house (revisiting the “unconscious,” or place of buried memories) and surrounded by his mother’s outrageous collection of “stuff” — statues, pieces of grotesque faux art, and garish furniture covered in cobwebs, which have been put into storage after her previous wild decorating sprees. Big Daddy, softened by the knowledge of the approach of his death, and ready to face some of the truths of life, sits amidst that piled-up junk in a moment of uncharacteristic vulnerability and tenderness.

Brick is still looking for love, with either man or woman. But Big Daddy had given up the search: “The truth is pain and sweat, paying bills and making love to a woman that you don’t love anymore.”

They begin an honest talk about Big Daddy’s cancer. Now, the inevitability of his demise shatters the family’s false-happy illusions and establishes the basis for an uncharacteristic tenderness between father and son. Their lifelong arguments at first resume, until Brick cries: “All I wanted was a father, not a boss! I wanted you to love me. We’ve known each other all my life and we’re strangers!”

Then Big Daddy recalls his own father: “I was ashamed of that miserable, old tramp….” Then he adds, unexpectedly, “I reckon I never loved anything as much as that lousy old tramp.”

Suddenly, tenderly recalling his father’s love, Big Daddy is open to loving his own son, which immediately links the three generations of men and breaks through the deadening barrier of pretense. Big Daddy’s love, expressed for the first time, frees Brick to transform himself from a self-preoccupied alcoholic to a man alive to himself and able to love; and through this transformation, he can now respond to Maggie’s womanhood.

Big Daddy and Brick, perhaps for the first time in a lifetime,cry together.

Then in a moment of wild and joyful emotional release, Brick smashes his mother’s ridiculous collection of discarded “stuff.” Throwing aside his crutches, he hobbles up the stairs, exultant with joy. Maggie sees his joy, and she tells the family that she has new life in her body, and that the family will now continue through a child that is Brick’s.

Gooper and wife laugh sarcastically; they say they have heard the begging and pleading through the bedroom walls at night, when Brick refuses to be intimate with Maggie, so they know this story of her pregnancy cannot be true. Big Daddy’s family and his inheritance, they insist, will continue only through them and their side of the family.

But Brick grabs his wife, full of joy, takes her to the bedroom, kicks the door shut, embraces her with spontaneity and love for the first time since the play began. He exults that it is true– that there will soon be new life in Maggie’s body as well.

And so the play ends.

by Joseph Nicolosi, Ph.D.

I am often asked, “If homosexuality is usually caused by an internalized sense of masculine inferiority, how do you explain the masculine type of homosexual?”

I explain it as follows. The reparative principle is the same: there is an eroticized attempt to capture the lost masculine self. The masculine type of homosexual man suffers the same internal sense of masculine deficit as the more androgynous or feminine type, but in boyhood, this man typically needed to develop an external “macho” persona to fend off emotional abuse. The very masculine actor, Rock Hudson, the quintessential “heart throb” of the 1960’s, confessed: “There is a little girl inside of me” (Davidson, 1986).

An early environment of severe humiliation has taught some masculine types of homosexual men not to show weakness and to have contempt for their own vulnerability. Bullying typically came from the father, an older brother or male peers at school. In these situations, to show weakness often provoked greater assault and so denial of their vulnerability was necessary for survival.

This maneuver into a hyper-masculine façade is a “reaction formation,” which entails, as Freud said, an “identification with the aggressor.” It is a primitive form of self-protection in which the victim gains a fantasy security by imitating the feared person (*).

This same shift in identity is also seen in the masculine lesbian who may have perceived her mother – and therefore femininity – as weak; such a person therefore joins, through identification, with her mother’s spouse (the father) and she becomes Daddy’s little boy.

The masculine-type homosexual man often displaces his own need for love, comfort and protection onto a younger, weaker male. This is similar to the situation we see in another sexual deviation, pedophilia, where the man may wish to “give love” to a boy as he wished he himself had been loved (although in a different, non-sexualized way) when he himself was a child. This “innocent young boy” image he is so drawn to, is a projection of the abandoned boy that still exists within himself. Self-psychology explains this displacement of his unmet needs onto the disavowed self as a form of narcissistic identification.

When this masculine type of homosexual man feels insecure, he resorts to the reparative sexual enactment of giving comfort to the frightened boy within, by seeking closeness with a vulnerable younger man. Therefore he is often attracted to the younger, less masculine type of male – the innocent, adolescent type of partner who represents the suppressed part of himself that had to be denied in order for him to survive his boyhood. So this masculine type of homosexual now gives protection and “love” (albeit sexualized) to the youth, something which he himself once longed for.

Therapy necessitates guiding the masculine homosexual client with such a background toward abandoning the false macho, hyper-masculine facade and discovering his genuine masculine self. A genuine masculine self is characterized by, among other things, a natural vulnerability. This process also necessitates resolving his childhood trauma of abuse and intimidation. Through this resolution, he no longer has the compelling need to reenact his reparative sexual fantasy.

————————

(*) This phenomenon is similar to the Stockholm Syndrome in which captives identify with their abductors. The case of Patty Hearst, heiress to the Hurst media empire, is another example. For two months, Patty was kept in a closet and “brainwashed” by her captors, culminating in her assuming their identity. A willing convert to their revolution, she took the name “Tanya” (a tribute to the wife of Che Guevara) and participated in the robbery of a San Francisco bank.

Reference:

Davidson, Sara (1986). Rock Hudson: His Story. New York: Morrow.

My name is Father Bob and I am a 41-year-old Catholic priest who is in residence in a diocese.

It was about a month after the passing of my dad when I decided to contact Dr. Joe.

A few years previous, I had found myself viewing gay porn that I had discovered on the internet, and acting out the feelings from the images every two to three months. That was pretty typical. The interval became every two to three months, and finally, every two months…. then once a month. That just told me to pick up the phone and give Dr. Joe a call.

It was an embarrassment, the shame of knowing that a priest shouldn’t be living this way, and that I did not live up to my moral and Catholic values.

A priest-friend of mine who is a professor, had introduced me to Dr. Joe in the 1990’s and so I always knew in the back of my mind that he was out there. I had a lot of pain around my relationship with my Dad. I knew that pain was much the cause of my SSA. So when Dad died, that was the proverbial “straw that broke the camel’s back” and that’s why I gave Dr. Joe a call.

During the last few years of his life, I had tried to bond with my father. I remember once pouring out my heart and soul, crying on the phone, wanting and begging and pleading with him to please go and do something with me or have a relationship with me. But of course nothing came of it. His idea of bonding was us going to Wal-Mart together when I would visit home. I guess when he died, I had nowhere else to turn.

When I began therapy, Dr. Joe stunned me the first therapy session when he told me that my problem is not homosexuality per se, but shame. I have to admit I didn’t understand what that meant, but I was at the end of my rope. I had nowhere else to go. I had hit rock-bottom. I believed him, and that message became clear, and then he said I could benefit from “Body Work.” I didn’t know what that meant but we did it anyway.

It took me at least a year to really grasp shame and the grieving process, so that was what first happened. Because my problem came up around homoerotic pictures, we agreed to have me face the issue, and so I pulled up a homoerotic image. It was a picture I pulled up on my computer, of a muscular guy with exaggerated genitalia. After the first sexual charge left, I was stunned when I felt a flashback from my childhood, being beat up by a bully. I remember feeling very scared. That took me to grief, which was so intense that it surprised me.

This all took me back to when I was a kid, walking home from school. Every once in a while I would get picked on, and I’ve always remembered that sense of dread and fear; I felt like a caged animal with nowhere else to go, and I basically had to sit there and let them beat me up and be totally terrified. It was that same feeling–the exact same feeling I was getting– when I looked at that picture I pulled up on my computer of that naked guy. When the truth of that connection hit me, the sexual feeling quickly left. In that moment, I had another accepting male role model there with me, which made the arousal vanish. But then, the awareness of the real grief came, full-force. Boy, it was powerful and unexpected.

Then– it was just like a camera flash– another memory popped up and the fear became even more intense. I was walking home from school on a sunny afternoon, and I remember getting beat up by another kid. He said: “Go ahead, take your best shot.” I couldn’t do it; I just stood there in front of him and thought “Oh shit, now what?” And he kicked me again– he gave me a roundhouse kick to the stomach, and then my little sister came to my defense. How many sisters do that for their big brothers? But that’s what happened, and that’s what I went back to. I suddenly saw the connection between these sexy guys and these bullies. Something about the fear of them made the experience feel sexual to me. Sounds weird, but true.

What made a difference for me in the therapy was learning to stay in my assertion, practicing what Dr. Joe taught me. I remember once, when I was whining, he “kicked my butt” verbally: “Bob, you know these things – you know the steps, you know the shame and fear and tightness and the Gray Zone and the resolution… so get with it.” I needed that.

What also helped me was finding other safe, salient males that I could turn to and tell them of my inner struggles with SSA. Relating to other men who were heterosexual really was the key. You know, you can’t just try to “get it out of your head.” You have to do the work, you have to connect with straight men.

When I first came to the therapy I didn’t realize that my relationship with my mother was a part of the problem. I had no idea. She was my confidante, and my world revolved around her. I would call her every single week without fail. She was my best friend, but when we got into an argument, she was always right and I was always wrong. I can’t remember a time when she ever admitted she was wrong. I confronted her about how she made me feel, and she kept saying: “ “I would never want to hurt you,” which I believe is true, but now it’s abundantly clear that she will never understand me. She is very kind and very nice and gracious, but she doesn’t understand how she comes across, how she affects other people, and how she disempowers me and shuts me down.

I remember how I saw the correlation between conversations or visits with my mom and my acting out sexually. One particular case in point; I had been in therapy for only a few months and I tried to discuss with her how I felt about Dad and how he abandoned me, and that was a mistake. She did not want to hear that. She protested how much he really loved me. Then I tried to tell her how she makes me feel, how I feel this or that, or how I get shut down or fearful when she talks about herself. Instead she kept on protesting how much she loved me and wouldn’t want to hurt me and then, rather than her trying to hear and understand me, it just became about her.

That following week I had an episode. I acted-out seven times in one night, over a 24-hour period, with the gay porn. I have to take ownership of my own actions and as a priest, I feel guilty about this. But I see how I get triggered when I’m around my mother. It took me a few years to see the connection but it is abundantly clear today. So, sadly, I must keep her at a distance.

My life right now is nothing like it used to be before. I no longer live in fear. Most importantly, when I feel any sort of shame moment, 90% of the time I catch the shame moment right in the moment. Sometimes it takes me a day to pick up on it. I know how to “check in” with myself. I can even do the EMDR if necessary, but I don’t live in fear. I now feel much more comfortable around men. I really feel more like a man amongst men. It wasn’t always like that. Today I could rattle off many names of guys who I am buddies with.

Now, I don’t allow myself to be enmeshed with women. There is a boundary which was not there before, which is there now. Especially as a priest, there are these women who want to make you their son or something. This is especially true for the older women, the matronly type. They are sweet but controlling, like my mother. I would let myself be “the good little priest” for them and feel responsible to talk to them after Mass. I’d stand there for a half hour as they went on and on about God knows what. Then I wondered why I felt like acting out.

There was one particular parishioner who is a matriarchal type of woman who fussed over me and drove me crazy. Now I always keep her at arm’s length and she gets the message. I feel so much better about myself.

I have always tended to be drawn toward larger, muscular men, football player types or certain body builders. I may feel an attraction still, but nowhere near as intense as it used to be. And most importantly, It does not cause me to act out. I know immediately to go to my body and feel the pain, and often times, I do feel the pain. The pain is not as intense as it used to be, like a year ago, but the pain is still like… yuk. I feel it in my chest and I stay with it for a minute, but I realize and remember an example Dr. Joe gave me in therapy; seeing a bigger man is like looking at a bigger horse, a big horse as opposed to a small horse…he’s just bigger, not better, and I see it more in that light today.

I realize now that big men can “set me off” because they remind me of bullies, and particularly of my father. From a boy’s perspective, his father is a hero, and in my case my father was this very large, overpowering and intimidating man. These large men represent my father, which represents overall masculinity in the world of men– unapproachable, untouchable, exotic, foreign, very different from me. So when I see a big man, I still get a whiff of that same feeling but I know it comes from the feeling of inadequacy, the shame-based self-statement that I am smaller and in a gender sense, inferior. I can accept the fact that I may be physically smaller– it is a truthful statement– that I can be physically smaller overall and in body parts too, but I’m OK with that. I know it doesn’t make me less of a man.