Homosexuality is not fixed and unchangeable, as these public figures reveal. Some of them celebrate their sexual fluidity as a good thing; others believe that the only true expression of sexuality is heterosexuality, since it is consistent with our biological design.

But the message is the same from all of them — people can change.

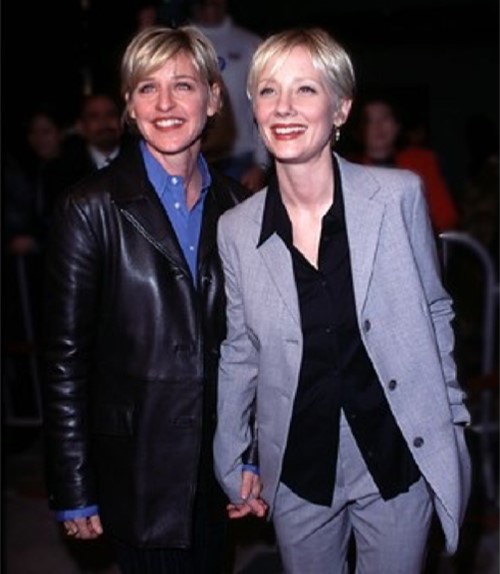

Anne Heche

Anne (born May 25, 1969) was an American actress who died in 2022. Her film credits include Six Days Seven Nights, Return to Paradise, I Know What You Did Last Summer, John Q and Volcano. She also starred in the television series Men in Trees, Hung, and, most recently, in Save Me, Dig and Quantico.

Heche and DeGeneres started dating in 1997, and at one point, said they would get a civil union if such became legal in Vermont. They broke up in August 2000.

Reporters asked “what the walls would say” if their $3.5 million L.A. pad could talk, more than three years after their going public with their relationship. “They’d be saying that we are very excited and we’re very happy and in love three years later,” DeGeneres said.

“Yeah,” Heche agreed. “We’re very lucky women, that we get to have what we have.”

“It’s a celebration every single day,” DeGeneres continued. “It’s kind of disgusting and crazy that we’re like … Oh, we’re so lucky.”

“Yeah,” Heche agreed. “We’re lucky, we’re so lucky.”[1]

Here statement about not being gay any more:

Anne then left Ellen DeGeneres to marry James Tupper.

From an interview:

[the interviewer] said “You were gay for a bit… you have an open mind.” Anne said “I have yes – had an open mind. But then I make decisions, ‘I have an open mind, but then ‘I’ve learned about that….fantastic’… I have an open mind, I can change my mind…There’s a door, we can close that door. We can go to another door.”[2]

Jessica Ellen Cornish (Jessie J)

Jessie J is an English singer and songwriter. She is the first British female artist to have six top ten singles from a studio album. The release of her third album Sweet Talker (2014) was preceded by the single “Bang Bang” which debuted at number one in the UK and went multi-platinum worldwide. As of January 2015, Jessie J had sold over 20 million singles and 3 million albums worldwide.

Her statement when she was gay:

She said in an interview:

If I meet someone and I like them, I don’t care if they’re a boy or a girl.

Her statement about not being gay any more:

From an interview about her previous lesbian attractions:

Passing comments [were] made into ‘facts’ that can never change. Guess what? They can change. As they should. And I have changed and grown up ALOT, and that’s allowed. And I feel more comfortable in my own skin now than ever before. We all are on a journey and I refuse to feel boxed and judged because of how I felt once! A long-ass time ago. Vegetarians eat meat sometimes. Get it? People change.[3]

Bob Dixon

Sen. Bob Dixon is an American Republican politician currently serving the Missouri State Senate who. Dixon was first elected to the house in 2002 and served four terms. Between 2004 and 2008 he served as Majority Caucus Chairman and chaired the House Transportation committee.

Statement about not being gay any more:

Missouri State Sen. Bob Dixon claims that childhood abuse and teenage confusion caused him to engage in gay relationships for a few years.

Dixon’s campaign issued a statement touting his faith in God and support for traditional marriage, while condemning any opponents who try to use his past against him.

“Through the years, I have publicly spoken about being abused as a child and the confusion this caused me as a teenager,” said Dixon in the statement. “There are literally thousands of Missourians who will understand how heartbreaking childhood abuse can be — though few might be willing to acknowledge it.

“I have put the childhood abuse, and the teenage confusion behind me,” said Dixon, who has a wife and three children. “What others intended for harm has resulted in untold good. I have overcome, and will not allow evil to win.”[4]

Julie Cypher

Julie Cypher is a film director who is best known as the former partner of Melissa Etheridge, a singer-songwriter, musician, and activist. Known for being one-half of one of the first “out” lesbian celebrity couples, Cypher advocated for gay rights. She and Etheridge then split and Cypher married Matthew Hale.

Her statement when she was gay:

Well, I was straight. I was married to Lou Diamond Phillips. I’d known lesbians as friends in college, but I’d never met a woman that I was attracted to, so lesbianism had never occurred to me—until I met Melissa. Then it occurred very strongly.[5]

From an interview with Cypher and Etheridge…

“Do you now consider yourself a lesbian?”

Cypher: “I absolutely do.”

“Would you be with a man again?”

Cypher: “I doubt it. I would look for the person, for the soul, but I just feel that the female psyche is where I find my satisfaction with relationships.”

Her statement about not being gay:

In 1999, she said, “You know, I’ve tried and I’ve tried these last couple of years, and I’m just not gay.”

Gillian Anderson

Gillian Leigh Anderson (born 1968) is an American-British film, television and theatre actress. Her credits include the roles of FBI Special Agent Dana Scully in The X-Files, ill-fated socialite Lily Bart in The House of Mirth (2000), and Lady Dedlock in the successful BBC production of Charles Dickens’ Bleak House.

In an interview with Out magazine, she described a lesbian relationship with a woman who had recently died.[7]

Her statement about not being in a gay lifestyle any more:

Anderson now identifies as heterosexual and has been twice married to men.

I am an actively heterosexual woman who celebrates however people want to express their sexuality. [8]

She is currently single, but looking to start a new relationship with a man.

Sheryl Swoopes

Sheryl Swoopes (born 1971) is a retired American professional basketball player and the head coach of the women’s basketball team of Loyola University, Chicago. She is frequently referred to as the “female Michael Jordan.”

Her statement when she was gay:

“I’m not bisexual,” she said. “I don’t think I was born [gay]. Again, it was a choice. As I got older, once I got divorced, it wasn’t like I was looking for another relationship, man or woman. I just got feelings for another woman. I didn’t understand it at the time, because I had never had those feelings before.”

One reporter at Out Sports explains the situation:

“Sheryl is just more proof that no one is born gay, it is a learned behavior brought on by experiences and circumstances in one’s life. I am very happy for Sheryl…”

Statement about not being gay any more:

From an interview when Swoopes was asked if she was “born gay”:

Swoopes: “No and that’s probably confusing to some, because I know a lot of people believe that you are.”[9]

Swoopes now has been twice married to men.

David Kyle Foster

David Kyle Foster is an author, professor, television producer, and the director and founder of Mastering Life Ministries. He has spoken on five continents about the healing of sexual brokenness, and has appeared on The 700 Club, The Dr. Phil Show, The Coral Ridge Hour, The Abundant Life, Cope, His Place, Home Life, and has been the host of Covenant Award winning “Mastering Life” on the Focus on the Family Radio Network.

What he said about having been gay:

“Because of my fear of mature women, I chose to see them as sexless ‘Snow White’ figures. My favorite actresses were Julie Andrews and Hayley Mills. When I became sexually active in my late teens, it quickly became far less stressful to go with males. Besides, most of the ones who came after me were older men who didn’t expect reciprocation or commitment on my part. Deep inside, I was still looking for ‘Father Knows Best”,’ and when older men gave me the time and attention that I craved, the results were almost inevitable.”[10]

What he says today:

Excerpts from David Kyle Foster’s testimony on the PFOX website: …

“Perhaps my personal witness to change can be of some help. I have been changed in many and varied ways over the past 32 years after seeking the Lord at the age of 29 to deliver me from a bondage to homosexuality, pornography and other sexually addictive behaviors. After 10 years of active involvement in the ‘anything but gay’ homosexual lifestyle, Jesus Christ revealed Himself to me and has set me free from what statistics show to be a death-style lain upon the foundations of profound brokenness….My identity has been completely transformed and I see myself as the heterosexual male that God had always created me to be.”[11]

Donald Andrew McClurkin (Donnie McClurkin)

Donald Andrew “Donnie” McClurkin, Jr. (born 1959) is an American gospel singer and minister. He has won three Grammy awards, and is one of the top selling Gospel music artists, selling over 10 million albums worldwide.

Statement about when he was gay:

McClurkin, in 2002, told a Christian website that, due to the sexual abuse of his earlier years, he had struggled with homosexuality.

Statement about not being gay anymore:

“I’ve been through this and have experienced God’s power to change my lifestyle. I am delivered and I know God can deliver others, too.”[13]

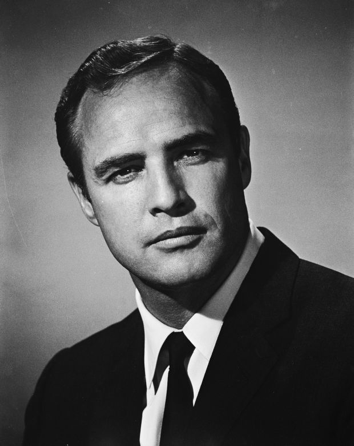

Marlon Brando

Marlon Brando was an American actor, film director, and activist. He was one of only three professional actors, along with Charlie Chaplin and Marilyn Monroe, named in 1999 by Time magazine as one of its 100 Most Important People of the Century.

Statement about hisinvolvement in homosexuality:

In 1976 he told a French journalist

“I too have had homosexual experiences, and I am not ashamed. I’d never paid much attention to what people think about me. Deep down I feel a bit ambiguous.”[14]

On living a straight lifestyle:

Brando ended up having several marriages with women— Anna Kashfi (m. 1957; div. 1959), Movita Castaneda (m. 1960; div. 1962), Tarita Teriipaia (m. 1962; div. 1972).

Dennis Jernigan

Dennis Jernigan is a singer and songwriter of contemporary Christian music. He is native to Oklahoma, and headquarters a music-based Christian ministry from there.

Statement about not being gay anymore:

From a blog by Dennis Jernigan…

“This statement will probably produce a lot of controversy, but this is how I think of myself: I do not consider myself a recovering/former/ex gay. I consider myself a new creation. The slate of my mind is being erased and the old thoughts are being replaced with new thinking. What I have discovered in the process is that when I change my thoughts, my attitudes change. When I change my attitudes, my behaviors change. When I change my behaviors, my perspectives change. When my perspectives change, I see life from a vantage point that homosexuality NEVER afforded me.”[15]

Dennis Jernigan lives with his wife Melinda (pictured together at left), in Oklahoma on the farm where they raised their nine children.

Chirlane McCray

Chirlane I. McCray (born 1954) is a writer, editor, and has worked in politics as a speechwriter. She is married to former New York City Mayor Bill del Blasio, and was the “First Lady” of New York City.

Statement when she was gay:

“I survived the tears, the isolation and the feeling that something was terribly wrong with me for loving another woman… coming to terms with my life as a lesbian has been easier for me than it has been for many.”[15]

Asked how she had left a lesbian lifestyle to marry a man, she explained it this way:

“By putting aside the assumptions I had about the form and package my love would come in. By letting myself be as free as I felt when I went natural.”[16]

Jan Clausen

Jan Clausen is the author of a dozen books in a range of genres. Clausen’s poetry and creative prose are widely published in journals and anthologies.

When she was in a gay lifestyle:

“After 12 years in a lesbian marriage, Jan Clausen fell in love with a man. Since her identities as writer and lesbian were intertwined, all hell broke loose. Clausen’s books are yanked off college reading lists. She loses friends, community, and status.”[17]

When she left the gay lifestyle:

Seeking to contradict the idea that people are born gay, she said,

“What’s got to stop is the rigging of history to make the ‘either/or’ look permanent and universal.”[18]

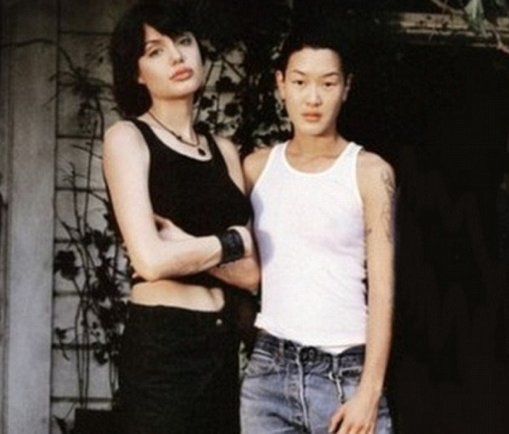

Angelina Jolie

Angelina Jolie is one of Hollywood’s highest-paid actress as well as one of the most influential people in the American entertainment industry.

With Partner: Jenny Shimizu

Statement when she was living as a lesbian:

In a 1997 interview with Girlfriends magazine:

“I fell in love with her the first second I saw her. ‘I would probably have married Jenny if I hadn’t married my [first] husband.’”[19]

Statement about not being in a lesbian lifestyle anymore:

Jolie spoke to Us Weekly soon after marrying Brad Pitt, saying,

“It’s been an amazing year. I married my love.”[20]

Michael Glatze

Michael Glatze was the co-founder of the group “Young Gay America” and a former writer/editor and passionate advocate for gay rights. Later, he received media coverage for publicly announcing that he no longer identified as a homosexual, and that he believed that a gay identity is not in harmony with our created design.

Statement about when he was gay:

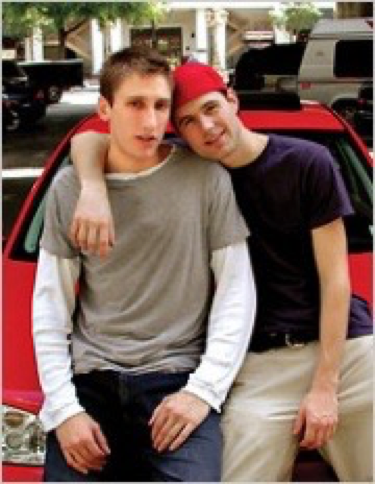

With former Partner: Benjie Nycum

“I was always a theoretical thinker, and I got into Queer Theory and I analyzed all the different facets of sexual identity, and I identified as queer.”[23]

Statement about not being gay anymore:

“Homosexuality, delivered to young minds, is by its very nature pornographic. It destroys impressionable minds and confuses their developing sexuality; I did not realize this, however, until I was 30 years old,”

Glatze wrote in an article in WorldNetDaily.

With spouse, Rebekah Glatze

“It became clear to me, as I really thought about it – and really prayed about it – that homosexuality prevents us from finding our true self within. We cannot see the truth when we’re blinded by homosexuality.”[24]

With partner: Michelle Clunie

“Best friends for 25 years, mother and father are both very excited about the upcoming birth and look forward to co-parenting the child together. The pair have been planning this baby for years and have been trying for the last two.”[26]

Wiki and Me:

My Battle with Wikipedia

by Joseph Nicolosi, Ph.D.

For almost a year now, I have been battling Wikipedia to remove false information about me. To date, they have ignored all of my attempts to correct their errors.

Most readers think that Wikipedia is a neutral, authoritative source. In fact, it is compiled by volunteers— not paid experts— some of whom (especially in areas of social controversy) are activists seeking to influence public opinion.

Specifically, my therapy is wrongly described in Wikipedia. In fact, I never tell SSA men that they should avoid opera and art museums; attend church; learn to mimic “straight” ways of walking and talking; join group therapy; begin dating and then marry, etc. Whenever I correct these areas on the Wikipedia page, the entries are promptly changed back into their original form by an activist writer.

To readers interested in the details of the error, they are described below.

—————

In the Wikipedia page on “Conversion Therapy,” under the subsection: Reparative Therapy, it states:

“Nicolosi’s intervention plans involve conditioning a man to a traditional masculine gender role.

He should—

(1) participate in sports activities,

(2) avoid activities considered of interest to homosexuals, such [as] art museums, opera, symphonies,

(3) avoid women unless it is for romantic contact,

(4) increase time spent with heterosexual men in order to learn to mimic heterosexual male ways of walking, talking, and interacting with other heterosexual men,

(5) Attend church and join a men’s church group,

(6) attend reparative therapy group to discuss progress, or slips back into homosexuality,

(7) become more assertive with women through flirting and dating,

(8) begin heterosexual dating,

(9) engage in heterosexual intercourse,

(10) enter into heterosexual marriage, and

(11) father children” (footnote #82).

Wikipedia Footnote #82: Bright, Chuck, (December 2004) “Deconstructing Reparative Therapy: An Examination of the Processes Involved When Attempting to Change Sexual Orientation,” Clinical Social Work Journal, 32, (4) 471-481,

(Note: The Bright reference is incorrect. It is not 2004 but 2001. The correct reference is: Bright, Chuck, L.C.S.W. (2001) “Deconstructing Reparative therapy: An Examination of the processes involved when attempting to change sexual Orientation,” Clinical Social Work Journal, December 2004 vol. 32, Issue 4, pp. 471-481.)

The description of my work is wrong— but even beyond the false content, we see that there is no traceable source for the false content.

In the Clinical Social Work article, Bright does indeed describe the 11 interventions as wrongly stated in Wikipedia, but he attributes them to someone else— Haldeman, (2001). Haldeman’s article is entitled “Therapeutic antidotes: Helping gay and bisexual men recover from conversion therapies,” referenced as being in A. Shidlo, M. Schroeder, and J. Drescher, the book “Sexual conversion therapy: Ethical, clinical, and research perspectives,” New York, NY: Haworth Press.

When we look at Haldeman (2001) we see that there is no such article in that book, by that title written by Haldeman. Rather, the Haldeman article is entitled: “Sexual Conversion Therapy: Ethical, Clinical and Research Perspectives.” That article contains no such pages as Bright references. Further, there is no such quote. In fact, Haldeman never mentions Nicolosi at all and neither does the Haldeman article reference Nicolosi.

Even if the “11 Interventions” were accurate descriptions of my therapy, it is apparent that the Wikipedia source attribution is incorrect and deserves to be removed. You would assume that Wikipedia would want to correct the error, if accuracy were a concern.

I will continue to battle Wikipedia to set the record straight. Stay tuned.

Lisa Nolland, an Anglican therapist from the U.K., pays tribute to the trailblazing psychologist whose work and thought have helped her ministry.

See article here: Joseph Nicolosi: A personal tribute to a great man | Anglican Mainstream

The book “A Parent’s Guide to Preventing Homosexuality” by Joseph Nicolosi, published by InterVarsity Press in 2002, has been reprinted by Liberal Mind Publishers for a 2016 edition.

Maximizing the possibility of a heterosexual outcome is important to most parents. No one can guarantee such an outcome, but there is much a parent can do to lay the critically important foundation for a secure gender identity. When a boy joyfully embraces his own maleness, heterosexuality will likely follow. In this book, Dr. Nicolosi offers not only the best parenting techniques, and he adds a sobering new chapter on the health hazards associated with a gay lifestyle.

Below are the comments of some of his colleagues.

What Others are Saying About A Parent’s Guide to Preventing Homosexuality

As a parent of a once gay-identified daughter, I can vouch for the wisdom and value of a loving but truthful approach to this predicament.

No truly loving parent would wish a gay identity on any child. In those societies where gayness has been celebrated for many years, we see the same poor health outcomes, instability, high suicide rates, and shortened lives associated with the gay lifestyle which are seen today in our own society. The good news is that social science shows that over the lifespan, gay people of all faiths and no faith tend, in many cases, to gradually move toward heterosexuality. Life experiences and completion of the task of maturation and emotional development often delayed for a variety of reasons, are the likely driving facilitators of this process. In the end, those years represent lost potential for knowing the enjoyment of the kind of relationships for which individuals are designed.

Parents should never give up hope, nor become a part of the gay- affirming culture. A loving parent remains true to what is true about sexuality, and supportive of all welcomed means of help for their children. Such a parent remains a vital part of their child’s life and that of their child’s partners, regardless of where that takes them. Dr. Nicolosi’s book provides hope and much-needed scientific medical facts to guide them.

— Keith Vennum, MD, LMHC, Licensed physician practicing psychiatry; President-Elect, National Assn. of Research and Therapy of Homosexuality

——-

Dr. Nicolosi’s book should be required reading for all future parents. His philosophical, psychological and scientific knowledge and experience are up-to-date and accurate on the topic of same-sex attraction and how to build young boys into strong men. I refer to his work many times during my work with psychiatric patients throughout the week. Dr. Nicolosi is truly an asset to the world community of psychology.

—Anthony Duk, MD, Psychiatrist; Board member, National Assn. of Research and Therapy of Homosexuality

——

According to a 2016 CDC report, men who have sex with men are 79 times more likely to become HIV-positive than heterosexual men. This fact alone makes Dr. Nicolosi’s book, Preventing Homosexuality, an invaluable resource for parents. The importance of gender-affirming parenting by mothers and fathers upon their children’s emotional development cannot be underestimated.

This book should be required reading by all medical students, students of mental health, and healthcare providers alike.

— Michelle A. Cretella, MD, FCP, Board-certified pediatrician; Vice President, American College of Pediatricians; Board member, National Assn. of Research and Therapy of Homosexuality

——

For over a decade I have shared Dr. Nicolosi’s insights in media outlets, seminars, classrooms, and on-on-one therapy sessions. Over the years, countless parents have expressed immense appreciation for the difference this information has made in both preventing and transforming gender confusion in their children. All parents need this vital information, and not having it can be detrimental. In fact, I’ll never forget one mother of a homosexual teenager who said, with tears streaming down her face, “Why didn’t someone tell me this when my son was two years old?”

The pain of gender confusion is preventable. This book is the solution to that deep level of pain and regret. It is my hope that all parents will have the opportunity to read this book!

— Julie Harren Hamilton, Ph.D., LMFT, Licensed Marriage and Family Therapist; Former President of the National Association for Research and Therapy of Homosexuality; co-editor of The handbook of therapy for unwanted homosexual attractions: A guide to treatment; former President, Palm Beach Association of Marriage and Family Therapists

——

Too often in contemporary society, parents are confused about the important role they have in their children’s sexual-identity development and the potential consequences of overlooking that role. Joseph Nicolosi does a masterful job of presenting relevant scientific literature and clinical insights that may not be politically correct, but certainly will help many parents navigate this challenging terrain more successfully.

—Christopher Rosik, Ph.D., psychologist, Director of Research at Link Care Center, Fresno, CA, Clinical faculty member, Fresno Pacific University; author of over 45 peer-reviewed professional journal articles; former President of the Western Region of the Christian Association of Psychological Studies (CAPS); former President, National Assn. of Research and Therapy of Homosexuality

——

This book is an invaluable resource for parents seeking guidance in raising children with the proper self-image. I have personally recommended it to parents who have come to me seeking guidance. In a world where there is so much distortion, confusion and misinformation regarding same-sex attraction, Dr. Nicolosi stands as beacon of light and truth regarding this critically important issue.

— Rabbi Avrohom Stulberger, President, Yeshiva Principals Council of Los Angeles, CA

——

In this second edition of A Parent’s Guide to Preventing Homosexuality, Joseph Nicolosi boldly and effectively provide parents with research-derived information and practical strategies. It is aimed at parents who seek to advocate for their children against the limiting cultural narrative of a permanent sexual-attraction identity.

I don’t know of a more important parenting book for our times.

—Carolyn Pela, Ph.D., psychologist, Chair of the Behavioral Studies Dept. and the Institutional Review Board at Arizona Christian University; President, National Assn. of Research and Therapy of Homosexuality

“Professional Malfeasance is Appalling Beyond Imagination,” Says Dr. Jeffrey Satinover

In recent years, the psychological professional has been accused by critics of becoming so ideological that it is no longer open to competing ideas. Few professionals remain, however, who are now willing to speak up. The career cost is simply too high.

For a historical perspective on this alarming process, the following article quotes Dr. Nicholas Cummings, who was a mainline psychologist and self-professed “liberal and promoter of diversity.” He once served as the president of the American Psychological Association (APA). The article was published in a 2005 NARTH Bulletin.

A.P.A.Past-President Charges His Association with Stifling Discourse and Distorting Research

In a harsh critique of his own profession, a former American Psychological Association president told fellow clinicians at the NARTH Conference nearly twenty years ago that social science was in a state of alarming decline. The situation has since deteriorated rapidly and now, in 2024, may be beyond repair.

Speaking to a rapt audience of about 100 fellow professionals at the Marina Del Rey Marriott Hotel on November 12, 2005, psychologists Nicholas Cummings, Ph.D. and Rogers Wright, Ph.D. had much to say about the profession they had served throughout their long and distinguished careers — charging “intellectual arrogance and zealotry” within a profession that they say is now dominated by social-activist groups.

Dr. Cummings said he has had a career-long commitment to promoting diversity. Therefore has been dismayed to see activists exploit the stature of the parent body to further their own social aims — pushing the APA to take positions in areas where they have no conclusive evidence.

When APA does conduct research, Dr. Cummings said, they only do so “when they know what the outcome is going to be…only research with predictably favorable outcomes is permissible.”

When writing their book Destructive Trends in Mental Health, Wright and Cummings invited the participation of a number of fellow psychologists who flatly turned them down–fearing loss of tenure, loss of promotion, and other forms of professional retaliation. “We were bombarded by horror stories,” Dr. Cummings said. “Their greatest fear was of the gay lobby, which is very strong in the APA.”

“‘Homophobia as intimidation’ is one of the most pervasive techniques used to silence anyone who would disagree with the gay activist agenda,” said Cummings. “Sadly, I have seen militant gay men and lesbians– who I am certain do not represent all homosexuals, and who themselves have been the object of derision and oppression– once gaining freedom and power, then becoming oppressors themselves.”

He described his own experience of oppression and reverse bias: “This was aptly demonstrated,” he said, “during an interchange that took place in a large meeting assembled by the then-current president to address the future of the APA. I was just about to agree with one of the participants, when she stopped me before I could speak: ‘I don’t know what you are going to say, but there is nothing you and I can agree on, because you are a straight white male and I am a lesbian.’ Such blatant reverse discrimination was overlooked by everyone else in the room, but I was dumbfounded. This woman is prominent in APA affairs, is extensively published, and has received most of the APA’s highest awards. The APA continues to laud her, even though recently she had her license suspended for an improper dual relationship with a female patient! What would be the response had it been a straight white male in an improper dual relationship with a female patient?”

Regarding treatment for unwanted homosexuality, the American Psychological Association came very close to ratifying a statement which would declare therapy to modify sexual orientation “unethical.” But “why does free choice go only one way?” Dr. Cummings asked.

Cummings then discussed a 2004 resolution by the APA in favor of gay marriage, which APA recommended because it “promotes mental health.” What was the evidence APA offered? (Such a bold statement from APA, of course, would be used in the courts to decide key social issues.) The references APA cited, it turned out, actually proved only one claim– that as a general matter, “loving relationships are healthy.” “That was one of the worst resolutions,” Cummings said.

“When we speak in the name of psychology we are to speak only from facts and clinical expertise,” he explained. If psychology speaks out on every social issue, “very soon the public will see us as a discredited organization–just another opinionated voice shouting and shouting.”

Cummings’ co-author Dr. Rogers Wright (who like Cummings, described himself as a lifelong liberal) notes that “psychology has been ultra-liberal” and not particularly welcoming to the views of people of religious faith.

Wright described the difficulties he has encountered with the American Psychological Association since the Association instituted a “strategic decision not to respond” to their book in an effort to avoid attracting attention to it. Initially, the APA prohibited its member-publications from reviewing Destructive Trends. “So much for diversity and open-mindedness,” Wright added wryly.

Judicial Malfeasance by Activists

Joining them in yet another stinging critique of the mental-health profession was psychiatrist Jeffrey Satinover, M.D. In his talk entitled “Judicial Abuse of Scientific Literature on Homosexuality by the American Mental Health Professional Organizations,” Satinover offered a long, elaborately referenced description of ethics breaches in the recent legal cases that have set the stage for groundbreaking changes in family-law policy.

Satinover said the mental-health associations had allowed themselves to be used by gay activists who distorted the research findings to serve their own socio-political aims. This distortion of the science, he said, has been so great that it is “appalling beyond imagination.”

Dr. Satinover has taught constitutional law at Princeton University, and is presently doing research at the University of Nice. He showed the legal briefs to his students and told them, “Whether you become a leftist or a rightist, don’t hold yourself to such a standard.”

Given carte blanche, the activists wrote briefs that were “sophisticated, nuanced” but in many cases, almost entirely untrue. To Dr. Satinover’s dismay, the brief-writers’ testimony rarely matched the references they footnoted–but almost never directly cited–as corroborating evidence.

Called as an expert witness in court cases and asked to assess briefs being submitted to state and the U.S. Supreme Courts, Satinover had the opportunity to pour over hundreds of research papers offered as evidence by the gay activists who had been invited to represent the views of the major mental-health associations.

He quoted Susan Cochran, Ph.D., a lesbian activist advising the Lawrence v. Texas brief, which claimed that “Research has…found no inherent association between homosexuality and psychopathology.” The references she provided were largely self-references — referring not to corroborating sources, but directly back to her own published work.

Paradoxically, in those same studies, Cochran had consistently found more mental-health problems in lesbians and gay men — and she did not find that “social homophobia” was a sufficient cause for these problems. In fact, Cochran had concluded in one of her own referenced papers that “further research is needed to explore the causal mechanisms underlying this association.” In a follow- up paper, she herself showed that the effects of social homophobia couldn’t account entirely for the association.

Satinover also offered evidence from the Romer v. Evans brief that evidently came from gay- activist psychologist Gregory Herek, Ph.D., who wrote the brief on behalf of the APA. Herek, he says, distorted the findings of the authors of the research he cited; omitted available contrary evidence; and failed to mention the evidence for spontaneous changes of sexual identity. Herek also defined the term “homosexual” in an arguable manner that worked most effectively to meet the aims of his brief–a definition that was the outcome solely of his own work, and that deviated from widely-used, neutral scientific standards. In support of the argument that same-sex attracted people are as well-adjusted as straights, Satinover said, Herek also referenced the “notoriously flawed and out-of-date Hooker study, its claims long-since and multiple times overturned.”

Pedophile Supporters Offering Family-Law Testimony?

In the Romer v. Evans case, psychologist John Money, Ph.D. was referenced as an expert in sexual identity. In an interview published in the Dutch journal of pedophilia (PAIDIKA), Money once said, “If it [man-boy sexual contact] is consensual, it can be constructive.”

Another expert offered by Herek was John de Cecco, Ph.D., who has also written affirmatively of man-boy “intergenerational intimacy” in the Journal of Homosexuality, and is an editor of PAIDIKA.

Yet one other frequent contributor to legal testimony, the Lawrence brief included, is lesbian activist-researcher Charlotte Patterson, Ph.D., who in a landmark case of same-sex adoption was cited for refusing to turn over her research notes, contributing to her side’s defeat. “Her conduct was a clear violation of a court order,” said Satinover, “yet she is still writing briefs in current court cases.”

In discussing the overall “scope and type of malfeasance,” Satinover concluded the following:

1. “Briefs appear to be authored by a small circle of individuals who are called on repeatedly, with footnoted references that almost never properly substantiate their case.”

2. A common tactic is to reference studies “that are trivial or out-of-date, while ignoring more important, recent, larger, better, and superceding research.”

3. “A substantial portion of the authorities cited [through footnotes] will be themselves.”

4. “The most common pattern is by far the simplest: the overwhelming mountain of contrary evidence is simply never mentioned.”

“The malfeasance is relentless,” Satinover concluded. “It is appalling beyond imagination.”

Charles Socarides

1922-2005

A crucial turning point in the history of LGBT political activism was the decision by the American Psychiatric Association in 1973 to declare that homosexuality was no longer considered a mental disorder.

The late Dr Charles Socarides, clinical professor of psychiatry and a founder of the National Association for Research and Therapy of Homosexuality, documented in detail the history behind the APA decision from a firsthand-witness vantage point. Along with a few other prominent psychiatrists including Irving Bieber, he tried to prevent the APA change, but their attempts were ignored or dismissed. All of the psychiatrists understood the motivating force that drove the decision– particularly, empathy for a population that was suffering from social discrimination– but they also knew that the decision, although motivated by benign impulses, would have unintended and far-reaching consequences.

Forty-five years ago, Dr Socarides predicted that if homosexuality was removed, the consequences would include:

-

Our understanding of what is healthy, normal or abnormal sexual behavior would have to be altered.

-

Sex education would have to teach homosexual conduct as normal.

-

Homosexuals wanting help would be in despair, because all of sudden, they wouldn’t have a condition that would justify treatment.

-

Dissatisfied homosexuals would be dissuaded from seeking therapy.

-

Suicides among persons with gender-identity disorder might increase.

-

Other medical disciplines would be affected, such as pediatrics.

-

Student doctors with a traditional understanding of sexuality would be unwilling to enter psychiatry out of fear of being branded bigoted.

How true were his predictions? Every one of them has come to pass.

Reference:

Socarides, Charles, “Sexual Politics and Scientific Logic: The Issue of Homosexuality,” 1992.

by Joseph Nicolosi, Ph.D.

“Being queer means pushing the parameters of sex and family, and in the process, transforming the very fabric of society.”

–National Gay and Lesbian Task Force Policy director,

Paul Ettelbrick (Kurtz, 2003)

Today, with homosexuality no longer a disadvantage in many Western cultures, the promiscuous nature of gay men’s relationships is being more openly acknowledged.

In 1948, Kinsey observed that long-term homosexual relationships were notably few. Now, more than fifty years later, long-term gay male relationships may be more common, but the fact remains that they are typically not monogamous.

In one notable study of gay male couples, 41.3% had open sexual agreements with some conditions or restrictions, and 10% had open sexual agreements with no restrictions on sex with outside partners. One-fifth of participants (21.9%) reported breaking their agreement in the preceding 12 months, and 13.2% of the sample reported having unprotected anal intercourse in the preceding three months with an outside partner of unknown or discordant HIV-status (1).

This study follows the classic research of McWhirter and Mattison, reported in The Male Couple (1984), which found that not a single male pair was able to maintain fidelity in their relationship for more than five years. Outside affairs, the researchers found, were not damaging to the relationship’s endurance, but were in fact essential to it. “The single most important factor that keeps couples together past the ten-year mark is the lack of possessiveness they feel,” says the authors (p. 256).

The gay community has long walked a thin public-relations line, presenting their relationships as equivalent to those of heterosexual married couples. But many gay activists portray a very different cultural ethic. Michelangelo Signorile describes the campaign “to fight for same-sex marriage and its benefits and then, once granted, redefine the institution completely–to demand the right to marry not as a way of adhering to society’s moral codes, but rather to debunk a myth and radically alter an archaic institution.” (1974, p 3).

Research Findings On Promiscuity

In 1968, Hoffman stated: “Sexual promiscuity is one of the most striking, distinguishing features of gay life in America” (p. 45). A much-cited study by Bell and Weinberg (1978), published by the Kinsey Institute, and often called the most ambitious study of homosexuality ever attempted, gathered its data before the AIDS crisis had begun. This study showed that 28 percent of homosexual males had had sexual encounters with one thousand or more partners. Furthermore, 79 percent said more than half of their sex partners were strangers. Only 1 percent of the sexually active men had had fewer than five lifetime partners. The authors concede: “Little credence can be given to the supposition that homosexual men’s ‘promiscuity’ has been overestimated” (p.82). “Almost half of the white homosexual males…said that they had had at least 500 different sexual partners during the course of their homosexual careers,” (p. 85).

A few years later, Pollak (1985) described sexual behavior among gays as “an average several dozen partners a year” and “some hundreds in a lifetime” with “tremendous promiscuity” (p.44). He said:

The homosexual pick-up system is the product of a search for efficiency and economy in attaining the maximization of “yield” (in numbers of partners and orgasms) and the minimization of “cost” (waste of time and risk of one’s advances being rejected). Certain places are known for a particular clientele and immediate consummation: such as “leather” bars, which often have a back room specially reserved for the purpose, saunas and public parks. (p. 44)

William Aaron’s autobiographical book Straight draws similar conclusions:

In the gay life, fidelity is almost impossible. Since part of the compulsion of homosexuality seems to be a need on the part of the homophile to “absorb” masculinity from his sexual partners, he must be constantly on the lookout for [new partners]. Constantly the most successful homophile “marriages” are those where there is an agreement between the two to have affairs on the side while maintaining the semblance of permanence in their living arrangement. [p. 208]

He concludes:

Gay life is most typical and works best when sexual contacts are impersonal and even anonymous. As a group the homosexuals I have known seem far more preoccupied with sex than heterosexuals are, and far more likely to think of a good sex life as many partners under many exciting circumstances. [p.209]

Emphasis On Sexuality

One writer – who, it should be mentioned, strongly sympathizes with the gay community about the stresses of social discrimination – observes conditions among gay men as follows:

It must be remembered that in the gay world the only real criterion of value is physical attractiveness…The young homosexual will find that his homosexual brothers usually only care for him as a sexual object. Although they may invite him out to dinner and give him a place to stay, when they have satisfied their sexual interest in him, they will likely forget about his existence and his own personal needs….Since the sole criterion of value in the homosexual world is physical attractiveness, being young and handsome in gay life is like being a millionaire in a community where wealth is the only criterion of value. [Hoffman 1968, pp. 58, 153, 155]

Aging is also viewed particularly negatively in the homosexual culture, with high value placed on youth (Bell and Weinberg 1978).

In his psychoanalytic study of ten couples, six of whom were homosexual, Gershman (1981) observed that in homosexual coupling, “sexuality is of greater importance and plays a larger role.” Gershman found that the majority of male couples he studied had agreed upon an open relationship, as long as the affairs were conducted discreetly. He found that while the male couples studied were capable of high compatibility in many other respects, there was great difficulty in maintaining sexual interest.

With the exception of the pioneering work of Warren (1974), for many years, little attention was given to long term gay relationships. When McWhirter and Mattison published The Male Couple in 1984, their study was undertaken to disprove the reputation that gay male relationships do not last. The authors themselves were a homosexual couple, one a psychiatrist, the other a psychologist. After much searching they were able to locate 156 male couples in relationships that had lasted from 1 to 37 years. Two-thirds of the respondents had entered the relationship with either the implicit or the explicit expectation of sexual fidelity.

The results of their study show that of those 156 couples, only seven had been able to maintain sexual fidelity. Furthermore, of those seven couples, none had been together more than 5 years. In other words, the researchers were unable to find a single male couple that was able to maintain sexual fidelity for more than five years. They reported:

The expectation for outside sexual activity was the rule for male couples and the exception for heterosexuals. Heterosexual couples lived with some expectation that their relationships were to last “until death do us part,” whereas gay couples wondered if their relationships could survive. (p.3)

McWhirter and Mattison admit that sexual activity outside the relationship often raises issues of trust, self-esteem, and dependency. However, they believe that

“the single most important factor that keeps couples together past the ten-year mark is the lack of possessiveness they feel. Many couples learn very early in their relationship that ownership of each other sexually can become the greatest internal threat to their staying together. (p. 256)

Other researchers have also seen sexual freedom as beneficial to gay relationships (Harry 1978, Peplau, 1982).

Yet in reality, there remains a contradictory longing for greater stability. In a study of thirty couples, Hooker (1965, p. 46) found that all but three couples expressed “an intense longing for relationships with stability, sexual continuity, intimacy, love and affection”- but only one couple in her study had been able to maintain a monogamous relationship for ten years. Hooker concluded, “For many homosexuals, one-night stands or short-term relationships are typical” (p.49).

The desire for sexual fidelity in relationships and the benefits of such a commitment are universal. In the long history of man, infidelity has never been associated with maturity. Even in cultures where it is relatively common, it is no more than discreetly tolerated.

Faced with the fact that gay male relationships are in fact promiscuous, gay writers have no choice but to promote the message that monogamy is not necessary.

Redefining “Fidelity”

McWhirter and Mattison believe that gays must redefine “fidelity” to mean not sexual faithfulness, but simply “emotional dependability.”

How can a relationship without sexual fidelity remain emotionally faithful? Fidelity as such is only an abstraction, divorced from the body. The agreement to have outside affairs precludes any possibility of genuine trust and intimacy.

A Clinical Understanding Of Gay Infidelity

Gay relationships are typically burdened with each man’s same-sex defensive detachment, and their need to compensate for that same-sex detachment. Therefore the relationship will often take the form of an unrealistic idealization of the other person as an “image.” In pursuing the other man as a representation the masculine introject that he himself lacks, many gay men either develop a self-denigrating dependency on the partner, or they become disillusioned because they discover “he has the same deficit I have.”

As he did in relationship with his father, the homosexual man fails to fully and accurately perceive the other man. His same-sex ambivalence and defensive detachment mitigate against trust and intimacy. When he becomes disillusioned, he will often continually set his hopes on the possibility of yet another, more satisfying partner.

In seeking out and sexualizing relationships with other males, the homosexual is attempting to integrate a lost part of himself. Because this attraction emerges out of a deficit, he is not completely free to love. He often perceives other men in terms of what they can do to fulfill his deficit. Thus, a giving of the self may seem like more of a diminishment than a self-enhancement.

A man who is depressed may gain a temporary sense of mastery through anonymous sex because of its excitement, intensity, even danger – followed by sexual release and an immediate reduction of tension. Later he is likely to feel disgusted, remorseful, and out of control. He feels regretful, regains control and feels all right again. But when there is nothing to “feed” that healthy state, it will be a matter of time until he gets depressed, feels powerless and out of touch with himself, and seeks anonymous sex again as a short-term solution to getting back in touch and feeling in control.

Often a homosexual client will report seeking anonymous sex following an incident in which he felt ignored or slighted by another male. Feeling shamed and victimized, he acts out sexually as a way of reasserting himself and getting something back he feels was taken from him. Once again, he feels guilty and has to repent or make amends. Many gay men become addicted not just to the sexual release, but to the entire compulsive, life-dominating cycle– if not through overt behavior, then through preoccupation and fantasy.

In these repetitive, compulsive, and impersonal sexual behaviors, we see a focused engagement with the object–with a desire for an intense relationship, but at the same time, a resistance toward genuine intimacy. Hoffman (1968) describes the “sex fetishization” found in gay life (p. 168), and Gottlieb (1977) points out the strong element of sexual fantasy that has become institutionalized in gay culture. Masters and Johnson (1979) also found that those fantasies tend to be more violent than those of heterosexuals.

Homosexual attraction is often characterized by a localized response to body parts or aspects of the person, but when interest in these traits diminishes through familiarity, there follows a loss of interest in the person as a whole. In comparison, “straight” men are generally, in my clinical experience, not as trait-fixated. While some men may envision their ideal woman as tall, blond, blue-eyed, and large-breasted, we hardly see a distinct disinterest in women without these specific traits.

The Problem Of Sexual Sameness

In homosexual sex, the “body parts don’t fit.” Therefore sex must be “individually enjoyed rather than mutually experienced” (p. 214) by a technique of “my turn – your turn” (p.214) and “you do me, I do you.” (Masters and Johnson, 1979). Where orgasmic episodes are experienced separately, considerable discussion is required for their negotiation.

Sexual sameness also diminishes long term interest and creates the need for greater variety, including other partners (Masters and Johnson 1979).

McWhirter and Mattison (1984) corroborate this viewpoint, saying, “The equality and similarities found in male couples are formidable obstacles to continuing high sexual vitality in their lasting relationships” (p. 134).

These similarities between two men provide one possible explanation for gay promiscuity. Women are “wired” for nurturance and child-rearing, and a stable primary relationship is necessary for their protection and the protection of their children. Thus a woman introduces a restraining influence into the relationship that two men will never experience.

Indeed, gay-activist social commentator Andrew Sullivan has found that as a gay man matures, his relationships will likely split between those men he is friends with, and those he has sex with, but that the two groups will not likely overlap. Gay men, he says, “have a need for extramarital outlets.” (1995, p. 95).

This “new order” approach advocated by gay activists is part of a general cynicism toward mainstream values and the possibility of monogamy. Churchill, for example, is a gay advocate a and strong critic of Judeo-Christian influence in society. His work in the social-science literature reveals a deep hopelessness about the possibility of enduring relationships, either homosexual or heterosexual:

It may be reasonably supposed that there never was nor ever will be any person who can fulfill all of the spiritual and physical needs of another person. Hence, husbands and wives alike must spend a good deal of time and effort in artful deception and flattery… They must sustain the illusion upon which their marriage is based and upon which their sexual relationship is justified. [1967, p. 301]

Churchill describes the “dreary” picture brought to mind by the term family man:

It is difficult…to imagine any person who is engaged with the world at large as a family man or a homebody. It is almost impossibility for any man or woman who is laden with the cares and preoccupations particular to family life to be very deeply concerned with others. (p. 305)

Of the traditional Judeo-Christian family, he says:

Far from being the source of each and every good, it is one source of a great many social and moral evils. If all the homely virtues are learned in the bosom of the family….it should not be forgotten that many of the more contemptible vices are also learned in the bosom of the family: complacency, jealousy, bigotry, narrow-mindedness, envy, selfishness, rivalry, avarice, prejudice, vanity, and greed. (p. 304)

Conclusion

Although homosexuals do lack cultural supports, such as the freedom in every culture to marry a same-sex partner, I believe this is not the cause of gay promiscuity. I believe the central cause of gay promiscuity is to be found in the inherent sexual and emotional incompatability between two males. Men were designed for women, and when some factor—psychological, biological, or a combination of both—interferes with that wired-in design, the freedom to marry a partner of the same sex cannot change the fact that “something’s not working.”

For additional data, see “Romantic Relationship Difficulties,” (pages 70-71), “Interpersonal Relationships,” (page 80-81) and “Promiscuity as a New Social Norm,” (pages 81- 83), in the Journal of Human Sexuality, Vol. 1, 2009, published by NARTH, www.narth.com.

Footnote

(1) Neilands, Torsten B.; Chakravarty, Deepalika; Darbes, Lynae A.; Beougher, Sean C.; and Hoff, Colleen C. (2010), “Development and Validation of the Sexual Agreement Investment Scale,” Journal of Sex Research, 47: 1, 24 — 37, April 2009.

References:

Aaron, W. (1972). Straight. New York: Bantam Books.

Bell, A., and Weinberg, M. (1978). Homosexualities: A Study of Diversity among Men and Women. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Churchill, W. (1967). Homosexual Behavior Among Males: A Cross-cultural and Cross-species Investigation. New York: Hawthorne Books.

Gershman, H. (1981). Homosexual Marriages. American Journal of Psychoanalysis 41:149-159.

Gottlieb, D. (1977). The Gay Tapes. Briarcliff Manor, NY: Stein and Day Scarborough House.

Harry, J. (1978). Marriages between gay males. In the Social Organization of Gay Males, ed. J. Harry and V. Devall. New York: Praeger.

Hoffman, M. (1968). The Gay World: Male Homosexuality and the Social Creation of Evil. New York: Basic Books.

Hooker, E. (1965). An empirical study of some relations between sexual patterns and gender identity in male homosexuals. In Sex Research, New Developments, ed. J. Money, pp.24-52. New York: Holt, Reinhart and Winston.

Kinsey, A. C., Pomeroy, W. B. and Martin, C. E. (1948). Sexual Behavior in the Human Male. Philadelphia, PA: W.B. Saunders.

Kurtz, Stanley, “Beyond Gay Marriage,” The Weekly Standard, August 4 – August 11, 2003, Vol. 8, No. 45.

Masters, W., and Johnson, V. (1979). Homosexuality in Perspective. Boston, MA: Little, Brown.

McWhirter, D., and Mattison, A. (1984). The Male Couple: How Relationships Develop. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Peplau, L. (1982). Research on homosexual couples: An overview. Journal of Homosexuality 8:3-7.

Pollak, M. (1985). Male homosexuality. In Western Sexuality: Practice and Precept in Past and Present Times, ed. P. Aries and A. Bejin, pp. 40-61. New York: Basil Blackwell.

Signorile, Michaelangelo, “Bridal Wave.” In Out, December 1994.

Sullivan, Andrew, Virtually Norman: An Argument about Homosexuality, New York: Knopf, 1995.

Warren, C. (1974). Identity and Community in the Gay World. New York: Wiley & Sons.

My name is Dan and I’m 16 years old. I was in therapy with Dr. Nicolosi for about 6-7 months.

Before therapy I was kind of an outcast, really not social with anybody except one person who was very shy like me. Then my parents found out I was looking at gay porn and thought I should speak to someone. At first I was kind of skeptical about it, but after the first session I was really captivated and I really was looking forward to it.

When I started to talk to Dr. Nicolosi I realized that there was a lot of information that hadn’t crossed my mind that I started thinking about. Maybe that was just another side of my brain opening up and thinking about these new things that I hadn’t thought of before.

For one thing, I never thought about the long-term effects of looking at gay porn. Would this mean I am gay? And what would that life mean for me long term?

My friends thought my being gay was fine, so in my head, I thought it was fine too. But I once I started realizing what’s going to happen when I grow up, it kind of changed my mind. From there it got me thinking about other things and more realistic things and that’s just the point to where I knew that I had to stay in therapy.

I was Skyping with my friend — this is before I told my parents. I always had my door closed, I was always locked up in my room, and this time they came in and they looked at my computer screen. I tried to hide the Skype chat, and it was basically about me asking my friend if I should come out to my parents, to tell them that I’m gay.

So at that point ironically I told my parents everything and from there they just thought of as many things as they could to respond to this. Then they contacted Nicolosi, thankfully. We were all stressed out and my dad was like on a research rampage, just trying to look for everything possible, and he was having some trouble finding what he could do to help, because he knows nothing about this, and it’s not like it’s something we can talk to other people about.

At first we tried this other therapist, but he really didn’t help. He tried to help, but it did not work for me. So my dad kept looking, and he found Nicolosi online. My dad said he had talked to Nicolosi and that basically the assumptions he could make about what had happened in my life, from hearing what my dad told him, were true. So I was like, OK, this guy is definitely something different than my last therapist, and it’s worth a try.

In therapy, we got into shame moments when I was young, moments with my friends that were traumatic. Those were the events that I hadn’t really thought would have a big effect on my life until they were brought up and given more thought.

I kind of dug deep into the meaning of those events and once you kind of analyze them you realize that all the emotions that were hidden because of those events kind of just spilled out and I kind of came clean. It really is a relief to do that because you just feel like you found the source of everything that has been going wrong in your life. It wasn’t just gay porn that was the problem, but it was how I saw myself with other guys.

When I was about 12 years old my best friend, Marco, made fun of me in front of some girls. It was a big shock and shut me down. I did EMDR with Nicolosi and got over it.

Once I started thinking about it I realized I shouldn’t have let little things like that bring me down because that’s something that Marco didn’t think about probably a minute after he did it, while that memory stuck with me for so long.

Another was the basketball memory of where I kind of messed up and I put a lot of blame on myself for one little mistake. We were doing like a practice drill and I cut a cone that I was supposed to go around and the coach called me out on it in front of everyone and because of that, the whole team had to run. That put a lot of guilt on me and made me think that this was my fault and all the other guys were going to hate me.

As much as the EMDR helped with the past shame memories with guys, what really helped me was growing in self-confidence and internal feelings. Going to social activities and stuff has definitely helped a lot too because I remember before therapy it would be a struggle for me to like, even order food at a restaurant, because of how nervous I would be.

When I started therapy I was at the point where I could look at a random guy on the street and get a really strong feeling inside like a heart drop and also kind of get that sudden shock of fear. So as time went on there were ups and downs but eventually I got to this point I can look at a picture for as long as I want and not even get any feeling.

Change isn’t something that just happens. There was a lot of self-focus and hard work but as time goes on and the truth comes out you realize that it’s not what you really want.

I see all this gay stuff on T.V. and if people want to find gay role models they can do what they want, but after what I’ve been through, I can see that it’s not really the thing for me.

My OSA (opposite-sex attraction) is a lot stronger, definitely. It’s to the point where my SSA was when I started therapy; that’s where my OSA is now. It, like, switched. The more l got myself thinking about what the SSA was all about, and what it was based on, the stronger the OSA got. I don’t have a girlfriend yet but female images can get me aroused, like the gay guys used to. I know I can get married some day, which was out of my mind before.

I was at a party last night actually and it was really fun and it made me realize all the things that I have been missing out on because of fear– Nicolosi calls it “anticipatory shame.”

I feel like my parents are still a little bit suspicious but they have a right to be. They have been going through this for a long time. Before I was just locked up in my room with the door closed and the only time I would come out was to eat. Now I’m giving them just the truth. Our bond has grown a lot more.

Yesterday me and my Dad ran over to swimming and later my uncle and grandma came over and we all had a BBQ. I used to avoid family and feel uncomfortable because I thought I was different.

One of the things I worried about was that I had already told my friends that I was gay, and they were all supportive, like I was a celeb. When I started to change, I worried they would be disappointed. The best advice I would give a guy like me would be not to worry if they’ve told friends. Don’t think about the effect it’s going to have on them, think about the effect its going to have on you. Your friends can say someone else is OK being gay all they want, but they are the ones who are going to get married to someone of the opposite sex and have a family.

Motivation is what is needed, because if someone doesn’t have the motivation they are not going to think about any of the realistic stuff, about what’s going to happen in the long run. Don’t give up as hard as it might seem; if you just keep pushing through it you’re going to get there eventually.

By the end of therapy, when I looked at gay porn I thought that it was nothing to get aroused over. Nicolosi made me see porn realistically. Now If I think about this guy and what he’s doing with his life and the pictures he’s taking to please other guys, the porn loses its excitement– in fact, it’s just ridiculous.

Last week was Prom Night and we were all just dancing in the bus, it was a party bus and it was pretty small and there were a lot of people and it was crowded and we were all just dancing and then that’s when I was dancing with Janet. We were dancing and she was getting really close and so was I, and I just felt myself getting aroused in a real physical way, and it was just like a really good feeling. It was one of those things where you don’t want it to stop. It was really good. I definitely think she noticed but she didn’t say anything. But she smiled.

“I was the quintessential kid that was set up for homosexuality on several levels. I didn’t identify well with my gender, growing up, for various reasons. I wasn’t close to my father at all. I was defensively detached from him, during a phase in my life where I was more attached to my sister and mother, and that kind of thing. I was also bullied by my peers because….”